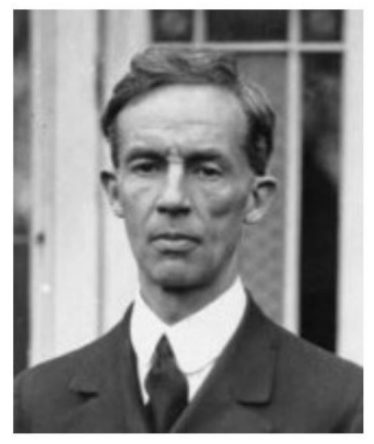

Erskine Childers: A Casualty of the Civil War, by Sean J. Murphy

All loss of human life is to be regretted, but the killing of Erskine Childers during the Irish Civil War in 1922 was particularly tragic. The Childers family, of Yorkshire gentry stock, established an Irish connection in the late nineteenth century through marriage ties with the Bartons of Glendalough House, Co Wicklow. The oriental scholar Robert Caesar Childers

married Anna Maria Barton, daughter of Thomas Johnson Barton, while his sister Agnes Alexandra Childers married Anna Maria’s brother Charles William Barton.

Bartons of Glendalough House

Both Robert Caesar and Anna Maria died of tuberculosis, leaving five young children, Henry Caesar, Robert Erskine (known as Erskine and born in London in 1870), Sybil, Dulcibella and Constance. The Bartons generously took the youngsters to Ireland to live with them at Glendalough House. Erskine Childers and his double first cousin Robert Barton moved almost in tandem from being supporters of the connection with Britain to becoming advocates of a separate Irish Republic.

Having secured a degree from Cambridge University in 1893, Erskine Childers entered the British civil service as an administrator in the House of Commons. At this stage he was attached to the imperial ideal and volunteered for military service during the Boer War. In 1903 Childers published The Riddle of the Sands, which warned against the developing German naval threat to Britain and has been dubbed the ‘first spy novel’.

Howth Gun running

Childers married Mary Alden ‘Molly’ Osgood, a member of a prominent Boston family. Indicating a growing radicalisation, Childers supported Home Rule and in July 1914 was involved with Molly in the Howth gun running using their yacht the Asgard, a gift from Molly’s parents, Dr Hamilton and Margaret Osgood. In April 1914 Ulster Unionist opponents of Home Rule had landed weapons at Larne. Co Antrim, and Nationalists sought to balance the situation by acquiring their own arms. At this stage the British government took no action, but the gun had well and truly been brought into Irish politics.

It should be noted that most members of the nationalist Irish Volunteers supported Britain in the war against Germany which broke out in July 1914. They believed that Home Rule would be granted to Ireland on the conclusion of the war. Thus Childers felt obliged to participate in the war, serving in British naval intelligence, while his cousin Barton also

signed up for military service.

A more radical faction of the Irish Volunteers led by Patrick Pearse and Tom Clarke staged a rebellion in April 1916 seeking to establish a free republic. This uprising was crushed by the British but their execution of Pearse, Clarke and other rebels leaders radicalised the situation. The Irish War of Independence was fought between 1919 and July 1921, when a truce was agreed between the British and the Irish rebels, followed by negotiations for a settlement.

Anglo-Irish Treaty

Barton and Childers had by then joined the republican camp and were key participants in the negotiations leading up to the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921. This Treaty granted twenty-six counties of Ireland the status of the Irish Free State, still subservient to the British Crown, while the other six counties remained under British rule as Northern Ireland. Barton was one of the Irish delegates who signed the Treaty under threat of renewed war from the British, but joined Éamon de Valera in opposing the agreement when he returned to Ireland. Childers, who was secretary to the Irish delegation, strongly opposed the agreement on the grounds that it conceded too much to the British, but was unable to persuade his colleagues, including his cousin Robert Barton, not to sign it.

Civil War ensued in Ireland, with Michael Collins leading the pro-Treaty Free State government until his death in August 1922 and Éamon de Valera leading the anti-Treaty

republicans. Both Childers and Barton took the Republican side, and found themselves targets of the new government.

Capture and execution

Childers had the misfortune to be captured during a visit to Glendalough House in November 1922 and was lodged in Wicklow Gaol. He was charged with possession of a small pistol (said to have been gifted to him by Michael Collins) and was found guilty of what the Free State government had declared to be a capital offence. Childers was shot by an Irish Army firing squad in Beggars’s Bush Barracks in Dublin on 24 November 1922.

Childers was not permitted to see his wife Molly before his death and his final letter to her ended with the words,

I die loving England and passionately praying that she may change completely and finally towards Ireland.

Childers was allowed to speak to his son Erskine junior, the future President of Ireland. Childers asked his son to forgive those responsible for his death, as he had forgiven them. These are words we should ponder as we mark the centenary of the Civil War, but it is debatable if any of the deaths on both sides of that terrible conflict were essential to establishing democracy. Childers’s widow Molly remained devoted to his memory and died in 1964.

Griffith’s allegation

The allegation against Childers of being a British spy while posing as an Irish republican is not supported by evidence. Indeed it would hardly have made sense for the British to have one of their operatives undermining the Treaty settlement they had worked so hard to secure. Nevertheless, there was great bitterness against Childers on the Free State side, best exemplified by Arthur Griffith’s insinuation that he was a British agent and a slur that he was a ‘damned Englishman’ during a Dáil debate in January 1922.

Burial at Glasnevin

Erskine and Molly Childers are buried in the Republican Plot in Glasnevin Cemetery, while their son Erskine Hamilton Childers, who served as President of Ireland from 1973-74, is buried with some other members of the family in Derralossary, Co Wicklow, near to the Barton plot. Erskine Childers has been described as an enigma, an over-zealous convert, a

British spy and a renegade. There is no doubt that his conversion from British patriotism to

Irish republicanism was remarkable and indeed ultimately fatal. The honesty of Childers’s

beliefs at all stages is undeniable, while the tragedy of his death is deepened by consideration of what more he might have achieved had he survived longer in an independent Ireland.

Further reading

Sean J Murphy, ‘The Barton and Childers Families of Glendalough House, Annamoe, Co

Wicklow’, 2018, https://www.academia.edu/37843137.

Childers (Robert) Erskine, Dictionary of Irish Biography,

https://www.dib.ie/biography/childers-robert-erskine-a1649.

Bob Conroy, ‘The Village of Annamoe’,

https://heritage.wicklowheritage.org/places/annamoe/the_annamoe.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page