This Dread Illness: The 1918/19 Influenza Epidemic in County Wicklow

In the churchyard adjoining the ruined church at Castletimon near Brittas Bay are a number of unmarked grave mounds, said to be those of fifty local residents who died of Spanish influenza. These anonymous victims are just some of the thousands infected and hundreds dead in Co Wicklow alone in the great flu pandemic of 1918/19. Arriving in Ireland in a relatively mild form in June 1918, the illness faded in July, only to revive with greater intensity in October. From December 1918 there was another lull, before it re-emerged once more in February 1919. In all, it has been estimated that 800,000 people in Ireland suffered from the disease, with a ‘conservative’ death toll of 20,000. Wicklow, together with four other Leinster counties – Kildare, Dublin, Wexford and Carlow – was one of the areas most severely affected, with a death rate of 3-4 per 1,000 living population, and a total death toll for Leinster of just over 6,000.

These figures are taken from Ida Milne’s 2018 study, Stacking the coffins, the definitive work on the incidence and impact of that particular pandemic in Ireland. Among the sources employed by Milne are contemporary accounts in national and regional newspapers, and this has prompted me to embark on an examination of the impact of the disease in Wicklow as reflected in its local weekly newspapers, the Wicklow People and Wicklow Newsletter. Supplemented here by information gleaned from the online GRO death records, they provide a reasonably comprehensive overview of the progress of the epidemic from its initial appearance in July 1918 through its various phases to its waning in April 1919.

‘The summer scourge’

The first intimation of the epidemic came in early June, when an influenza-like illness was reported in Belfast, with the caveat that there was ‘no cause for alarm.’ By 25 June the ‘mysterious scourge’ had reached Dublin and north Wicklow, with the manager of Glencree Industrial School at Enniskerry inserting a notice in the Irish Independent banning visitors until further notice. It took a little longer for the provincial press to react: the earliest reference in the Wicklow papers to the ‘new influenza’ was in the Wicklow People of 6 July 1918, which reported that the epidemic was ‘raging’ in Britain, while in Ireland ‘few places are now free’ of ‘the summer scourge.’ There were said to be 700 cases in Dublin, in Cork people were falling ‘prostrate in the street’ from the malady, and in Derry there had been ‘numbers of deaths.’ No mention was yet made of the incidence of disease in Wicklow. However, the following week’s Wicklow Newsletter reported a few cases in Arklow, while noting that the town in general ‘sails along quite unconcernedly and very little affected by the sickness.’ Meanwhile, Rathdrum had suffered ‘a good deal’, and ‘places like Bray that boast of their advanced sanitation’ had been ‘stricken’.

Arklow’s confidence was shortly shown to be misplaced. Its first victim, P J O’Donnell, was an employee of Kynoch’s munitions factory, and the funeral was a large one with many workers taking part in the procession. At the same time, a number of ‘mostly … mild’ cases were reported from Wicklow, and on 5 July an outbreak at Kilquade led to the closure of schools there. The epidemic was said to be ‘extremely severe’ in Bray, and in mid-July to be ‘raging’ in Hacketstown district., while ‘half the population of Tullow’ was reportedly infected, including the doctor and chemist, ‘so that those who are ill may look after themselves.’ Blessington was also badly hit, with almost all of its GAA players ill, and two of the most prominent, Edward FitzSimons and Bertie Hanlon, dead.

These deaths are a reminder of the disproportionate impact of this particular epidemic on young adults. Other young Wicklow people noted as dying of flu during these months included May Dooly (18), also of Blessington, and from Bray, Patrick Usher (25), a labourer, and Catherine Bermingham (27), wife of a railway employee. News reports also reveal the burden on health personnel: Dr Eccles of Delgany was laid up from early July until mid-August, while Miss Bolger, an infirmary nurse, sought sick leave from the Shillelagh Guardians in early August, because ‘she had been rather seriously knocked up with influenza’. Her request was approved, albeit somewhat ungraciously, with one member of the board grumbling that he supposed ‘we can’t get over granting it.’

By late July, in Wicklow as in the country at large, the epidemic appeared to be on the wane. In Hacketstown, for instance, it was reported that most sufferers were ‘on the convalescent list, and no new cases have been reported during the past week.’ Life, as reflected in the pages of the local press, returned to normal – or as near normal as could be expected with the war grinding to its conclusion and separatist nationalism on the rise. But the ‘summer scourge’ was set to return, and in a far more malign form than its predecessor, with Wicklow once more very much in the front line.

‘Black November’

Bray

On 12 October, just three months after accounts of its disappearance, the Wicklow Newletter announced the return to Bray of the ‘dreaded’ influenza. Within a week the Union hospital at Loughlinstown was reported full, and there had already been several deaths in the area. Among the first victims were Bridget Howell (19) and Mary Cecilia Darcy (20), buried within three days of one another in Little Bray cemetery. Bridget’s father was assistant stationmaster at Greystones, while Mary Cecilia’s was a railway policeman. A third influenza death of several in Bray that week was of Mary Ellen Turner (38), wife of an engine driver. The fact that a number of these early casualties had connections with the railway is interesting: although Milne queries the part played by train travel in disseminating the disease in Ireland, this cluster of cases tends to suggest that in Bray at any rate it may have been a factor in introducing infection into the district.

Whatever its origin, the epidemic in Bray raged throughout October. Patient numbers continued in the hundreds, and on just one day, Sunday 20 October, there were ten funerals in the town. At its height, Rathdown Board of Guardians was engaging six doctors to carry out the duties of the usual one (who was himself ill) and the master of the Workhouse reported that there had been 133 influenza admissions to the hospital during the previous fortnight. Little Bray was particularly badly affected, and with nursing assistance at a premium, the Sisters of Mercy fitted up their school at Ravenswell as a hospital for ‘upwards of 30’ patients. Many wives and children were left destitute with the death of the sole breadwinner, and there were particularly tragic cases of multiple deaths in one family. They included brothers Patrick and Henry Barry, both carpenters, who died within a few days of each other, and, saddest of all, the four children of Alexander Brien of Little Bray, all dead in a single week of double pneumonia.

Another noteworthy case, which links this tragedy with another of the period, was that of Mary Archer, wife of John Archer, an employee of the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company. Mary was already ill on 10 October when word came of the sinking of the ‘Leinster’ just outside Dublin Bay. Fearing that her husband was among the victims, she left her sick bed and hurried to Kingstown, where she learned to her relief that he was not one of the crew on that particular voyage. But the effort brought on a relapse, and she died on 5 November, leaving six children. Among the many other deaths to attract attention was that of Sister Mary Theresa Leonard of the Sisters of Charity at Ravenswell. An experienced nursing sister, Sister Leonard had assisted in the organisation of the hospital there, going on to nurse among others her own Reverend Mother, who recovered. However, she herself subsequently contracted pneumonia, and died on 10 November at St Vincent’s Hospital.

Greystones

While a report in mid-November claimed that Greystones ‘has not escaped the ravages of the epidemic any more than its neighbours in other parts of the county’, the district does appear to have been relatively unscathed if the absence of accounts of flu deaths in the local newspapers is to be believed. On 16 November the Newsletter announced ‘with much regret’ the death of Private R Johnston of the Royal Flying Corps. However, Private Johnston, who had worked for thirteen years as chauffeur to Dr Jameson of Greystones, did not die in Ireland. Having signed up with the Royal Flying Corps just five weeks previously, he had contracted pneumonia while training in England. His body was returned to Greystones, and he received a military funeral in Delgany on the following day. On the other hand, it must be remembered that most deaths never found their way into the newspapers, and the area did undoubtedly witness its own share of influenza fatalities. They included, in October 1918, Susan Jane Evans of Greystones, Bridget Gorman of Blacklion and six-month old Mary Doran of Redford, and a further trawl of the civil records would undoubtedly uncover more such examples.

By late October, the epidemic had made its way to other parts of the county. In Newtownmountkennedy the victims included Patrick Conroy, district postmaster, whose ‘coffin was borne by six rural postmen from the hearse to the graveside.’ ‘A very large proportion of the people’ in Rathnew had been laid up, and the several deaths included two young men who epitomised opposing sides in the emerging political debate. Private George Newsome died in barracks in England, but it was assumed that he had contracted influenza while home on leave just a week before, while Alexander Byrne was an active Sinn Feiner and a keen supporter of the GAA, whose funeral was attended by representatives of both bodies and members of Cumann na mBan.

Rathnew: Nurse Hayden

However, Rathnew was at least fortunate in having ‘the devoted and untiring’ services of Nurse Mary Hayden, who was universally praised for her work:

‘A few more like her in each district’, the Newsletter of 16 November declared, ‘would have made the task of the medical men less difficult … and saved, very probably, numerous lives.’ In due course, evidence of Nurse Hayden’s ‘splendid work’ during the epidemic would be laid before the Rathdrum Board of Guardians. ‘She had been offered a salary to work elsewhere’, the Board heard, ‘but she refused it’, remaining in Rathnew and thereby preventing ‘a lot more deaths in the district’, and it was decided to acknowledge her exceptional services by granting her a bonus of £10.

Wicklow

In Wicklow, meanwhile, there were reported to be about 1,000 cases, with two or more deaths occurring each day. Here, as elsewhere, the doctors found themselves overwhelmed with work, and although the County Infirmary, Fever and VAD Hospitals were all in use, hospital accommodation was still insufficient to meet the need. All sectors of the population were represented among the victims, who included De La Salle Brothers John Kearney and Paulinus Shiels, soldiers Privates Peacock and Ellis, butcher William Dunne and Wicklow Urban Council employee James De Courcey. Also dead were Mrs Keddy, labourer’s wife and mother of seven children, the baby daughter of Laurence Byrne of the Wicklow Hotel, retired postman William Olohan, whose daughter, Mrs Flood, also lost her husband and a child to influenza, and RIC Constable Laurence Corcoran, whose wife died of influenza a week later in Mayo.

By the middle of November the epidemic in Wicklow seemed to be abating, but was observed to have spread to rural areas such as Roundwood and Barndarrig, presenting the doctors with further difficulties in terms of travel and the scarcity of nursing care. At the same time, seventy-nine cases of influenza were admitted to Rathdrum Union Hospital, where some of the nurses and attendants and a number of the existing patients also contracted it. Eight patients had died, and the hospital was reported greatly overcrowded.

Arklow

Further down the coast, in Arklow, there was a theory, fuelled perhaps more by hope than expectation, that the town would escape the worst effects of the malady ‘by reason of the sulphur fumes from [Kynoch’s] factory, which would cleanse the air of the microbes that cause the sickness.’ More realistically, the local authorities, in co-operation with Kynoch’s, embarked on a systematic campaign of cleansing and disinfecting drainage, lanes and ashpits. Nevertheless, by the beginning of November, the disease had taken hold. Three weeks after its appearance ‘at least half a dozen deaths’ were reported, with whole families laid low. ‘In one family’, the Newsletter of 9 November recorded, ‘the parents and ten children were ill, and two infants succumbed to the disease within the week.’ Again, the medical services had to be extended to deal with the emergency: the Fever Hospital was opened for admissions, while the Masonic Hall was given over for use as an auxiliary hospital. Avoca was also reported to have suffered badly, with ‘entire families, both in the village and the district … laid aside’ and a ‘particularly severe’ death toll, which included, as elsewhere, a disproportionate number of young people.

West & South Wicklow

In the west and south of the county the epidemic was reported to be ‘raging seriously’ in Carnew, and practically the whole population of the wider Carnew/Shillelagh area was affected, with the schools expected to be closed there until after Christmas. The flu reached Tinahely quite early in October with an outbreak of ‘extraordinary severity’: once more, rail workers were among the early victims, with the whole station staff ‘prostrated’, and the stationmaster, William McGuire among the fatalities. Also ill were all the police and many of the postmen, shopkeepers and their clerks. Indeed, it was reported that very few in the district, including the local curate, escaped infection. There were also deaths in Kiltegan and Baltinglass, including several in the Workhouse there during November 1919. Other Baltinglass victims included grocer’s wife Sara Kitson, nine-year old Bridget Duffy and three young men in their twenties: Thomas Phelan, carpenter, James Jackson, blacksmith, and Christopher Timmins, shopkeeper. In Christopher’s case, as in that of many other young male fatalities, the report focussed on his sporting prowess: ‘a familiar figure on Gaelic football grounds’, a former player with Carnew Emmets and Baltinglass Shamrocks, and ‘a more sterling player never did duty for Wicklow.’

A particularly graphic account of the epidemic’s effects comes from Hacketstown: ‘schools closed, mails undelivered, doctors ill, death a frequent visitor, more than half the entire population of the town prostrate, business practically suspended.’ Twenty deaths occurred in this one small town during the first two weeks of November, of which ten were of children under five, eight between seventeen and thirty and the remaining two over seventy. Although few households escaped suffering, a few stories stand out as especially tragic:

A child, its mother and grandmother died in one house, a father and son in another, a young man and his grandmother in a third, while four children in one family, three in a second, and two in a third, died within a few days of each other … In no other family did the Grim Reaper pay so many visits as to that of Constable O’Halloran, who lost four of his five children inside a week, and to add to the tragic series of events, his sister-in-law, who came from her home in Tipperary to help her sister in nursing the children, contracted pneumonia and died in a few days.

Signs of abating

By the second half of November the epidemic had shown signs of abating. While fresh cases were still occurring in Bray in mid-month, ‘there is every hope that in a short time all traces of the disease will be eradicated.’ Similar reports came from Arklow and Rathdrum as well as Wicklow, and even in hard-hit Hacketstown the disease was said to be ‘well in hand.’ By the end of November Rathdrum Board of Guardians heard that ‘cases were not coming in with anything like previous frequency, which would suggest that in most districts in the Union the epidemic was on the decline.’ Deaths did continue into December: among the young lives cut short were those of Gretta Cullen (14), Ballyedmond, Hacketstown, and Michael and Andrew Byrne, the 15 and 11-year old sons of Michael Byrne of Ballycreen Park, Aughrim, who died on 8 and 9 December respectively. Increasingly, however, reports of disease and death gave way first to celebration of the Armistice which brought to an end four years of war, and then to preparations for the forthcoming general election. Schools began to re-open across the county, and social events, many of which had been postponed or cancelled, resumed. ‘Black November’ was over, a new era and a new state was taking shape out of the ruins of the past, but the epidemic, as events would show, still had a final card to play.

‘Flu here again’: February – April 1919

Items headlined in the Wicklow Newsletter of 15 February 1919 included the new Provisional Government’s deputation to the League of Nations, labour unrest among railway and postal workers, and the proposal to erect a memorial in Bray to the local dead of the recent war. And, alongside these events of national and local significance, a few lines heralded an unwelcome but all too well-remembered guest: ‘The Influenza Again’, it announced, reporting that there were now fifty cases in Bray. Similar reports came from ‘severely hit’ Greystones and Delgany district, where schools had been closed, and from Wicklow, where nearly a dozen patients were under treatment. Eighteen cases had been admitted to the Union hospital in Rathdrum, over fifty were currently being treated in Dunganstown, and ‘a rather serious outbreak’ had occurred in the Workhouse in Shillelagh.

By mid-February several deaths had been reported in the North Wicklow area. They included Dr Neale of Enniskerry, former Unionist parliamentary candidate Hon Hugh Howard of Delgany, and Bray Town Clerk Denis Mulally. The Downs claimed one of its first victims on 22 February, with the death of twenty-year old Michael Dobson, a member of the Delgany Erin Band and of the Irish Transport Workers’ Union, both of which were represented at his funeral in Kilquade. In Bray, where on one day there were seven deaths, some of the early fatalities included six-year old Alfred Bailey, a plumber’s son, and Catherine, ‘the darling child’, aged one year and nine months, of policeman James and Minnie Hennessy. Others included Jane Carr and her five-year old nephew, William Carroll, both of whom died on 28 February, as did Bartholomew Naylor, proprietor of the Bray Head Baths and a well-known local personality. Victims of the ‘very bad’ outbreak in Enniskerry included five young inmates of Glencree Reformatory, who died between 25 February and 6 March, and the wider Glencree area was very badly hit, with over 200 cases and no doctor immediately available.

Shops and schools closed

Meanwhile, influenza had reached Wicklow and its hinterland, with about eighty cases in the Wicklow dispensary district, and over fifty in Barndarrig. Many entire households were laid low, shops and schools were closed, and several cases at the Assizes had to be adjourned because of the absence of litigants or witnesses. Milk was ‘excessively scarce’ for several weeks, while whiskey, described by Milne as ‘perhaps the most widely available and effective treatment for the symptoms of influenza’, was in high demand: consequently, as the Newsletter noted, ‘it was almost impossible to get “a half-one” any day.’ Among those reported sick were some of the County Council clerical staff, RIC Constables Lewis and McMahon and two of the Christian Brothers, while the dead included Thomas Kavanagh, labourer, Samuel Stringer, gardener, Mrs Dora Stevens, wife of a cycle and motor agent, and the ten-month old son of Major and Mrs Truell of Clongannon. Mrs Truell herself was ill when her baby died, and two weeks later suffered the additional loss of her four-year old daughter.

On 25 February Bray UDC passed a resolution categorizing influenza as a notifiable disease. Schools were advised to close, the general public was encouraged to avoid crowded places, the public library was closed in order ‘to avoid the danger of infection being transmitted through books’, and ‘the co-operation of everyone in the district is invited to prevent the spread of disease.’ There were, however, continuing difficulties in ensuring the availability of medical attention and hospital accommodation. Doctors struggled to meet the ever-growing levels of need, and the Board found it extremely difficult to procure assistance or substitutes when doctors themselves fell sick. When Dr Raverty reported ill on 4 March, for example, all three of the practitioners approached were too busy with their own patients to do duty for him. A week later, Dr Craig, appointed to cover Little Bray, himself fell ill, leaving the area unattended for a weekend.

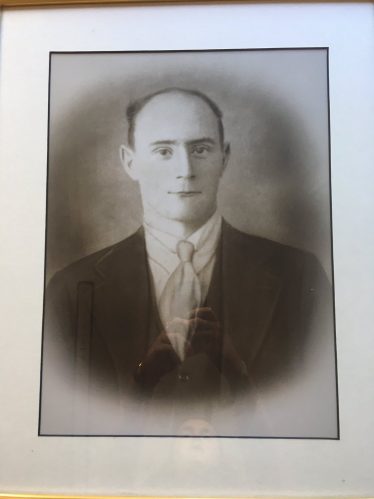

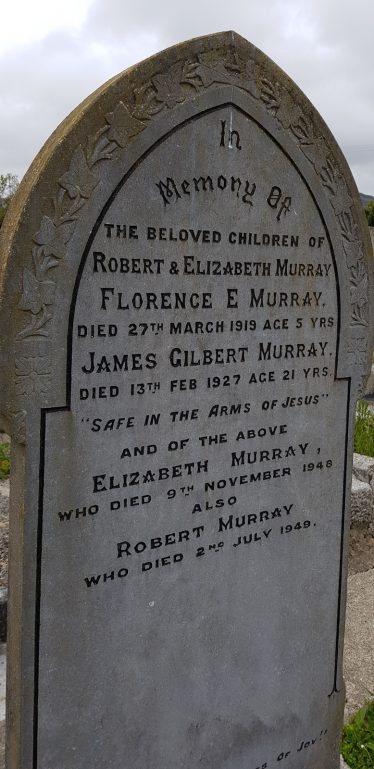

Among the Bray deaths recorded for these weeks were those of William Temple and Thomas Dodd, both of Little Bray, Mrs Edith Brown, sister of Dr Hanson, at Prince of Wales Terrace, and at Glencormack mother and son Margaret and one-year old Andrew Toole. Two of the local RIC constables were ill, as well as one at Enniskerry and three at Greystones, where there had been a number of deaths. They included several children: Winifred Collins (2) of Rossinver, Greystones, Florence Murray (5) and Patrick Pierce Redmond (1 year 9 months), as well as John Gorman (3) of Windgates, and his mother, Elizabeth.

Rural Wicklow hit hard

By the beginning of March the epidemic was cutting a swathe through the rural parts of the county: on 2 March a former soldier, William Morris of Kilcommon, Tinahely, died of pneumonia. Sadly, after four and a half years’ war service, Morris was under treatment for ‘exhaustion psychosis’, and had only been home a week when he died. Cases and some deaths were also reported in Shillelagh, Hacketstown and Moyne. And, while it was on the wane in Wicklow itself, in outlying localities such as Mullinaveigue, Moneystown and Roundwood, as well as Newtown and Kilpedder, the epidemic had escalated alarmingly, with ‘almost every household … laid down with the dread illness.’ Togher Agricultural Day, an annual event involving a ploughing match and other rural sports and activities, noted a reduction in the number of competitors owing to the prevailing epidemic, which ‘has made its appearance in strength in the locality’, with some ploughmen ill, others recovered but fearing a relapse, while a few were mourning family bereavements due to the influenza.

A particularly poignant notice from this part of the country recorded the loss of one Martin Farrell, a thirty-six year old illiterate labourer. ‘An extraordinary character’, his local popularity was due to his talent as a ‘whistler’ or ‘warbler’, a skill much valued ‘in days gone by when the flute and the fiddle were less in evidence in the district than at present.’ Martin, aged thirty-six, died at his home at Castlekevin on 30 March following a week’s illness.

Kynoch’s munitions factory

Reports from Arklow throughout the first weeks of March tended to minimise the local impact of the epidemic. By mid-month, however, the Newsletter was reporting that ‘the virulence of the influenza … has grown in intensity daily, and several deaths have occurred.’ These included yet more double tragedies: Arthur Kelly, a former Kynoch’s employee, died on 31 March and his sister, Mary Kelly, on the following day, while Sarah Anne Murray of Rockbig died on 18 March and her father, Laurence Murray, a week later. ‘On the one day last week’, the Newsletter reported on 5 April, ‘there were three funerals from different parts of the town, all being victims of influenza.’

In early April Bray Urban Council heard that ‘the influenza epidemic had died down … the schools are re-opened’, and the Medical Officer was going on a fortnight’s leave. This turned out to be somewhat premature: a couple of weeks later it was reported that there had been a recurrence of the disease in Bray, ‘and four or five deaths … already.’ These included RIC Constable Joseph McGoldrick, who died on 11 April, and Agnes Lynch, who died on the following day. Constable McGoldrick was recently married, and his wife was reported also to be seriously ill at the time of her husband’s death. Agnes Lynch had been in charge of Brennan’s Parade Post Office, and was consequently ‘brought closely into contact with the public.’ Bray Sinn Fein Club, of which her brother was Vice-President, was represented at her funeral, and Bray Cumann na mBan passed a vote of sympathy on her death. These were only two of several deaths during this final phase of the epidemic in Bray: at least eleven others from influenza or pneumonia are recorded for the area during the first two weeks of April.

There was also a resurgence of the disease in Wicklow in late March/early April. Local doctors Lyndon and McCormack, as well as ‘several prominent townspeople’ were among the sufferers. At Ballycurry gardener James Hamilton was reported dead of influenza, ‘in the prime of life’, Sergeant O’Grady of the Machine Gun Corps, a veteran of the Boer War as well as of the more recent conflict, died on 7 April in the VAD Hospital, having arrived home on leave just a week before, while Richard Codd of Roscath, ‘a popular sportsman’ and farmer, died on 19 April. Shillelagh, too, saw a ‘serious reappearance of the flu’ in late April, delaying the re-opening of local schools, and as late as June a patient suffering from influenza was transferred from the workhouse there to the Fever Hospital. By that time, however, the topic of the epidemic had all but disappeared from both Wicklow newspapers, as attention turned to more mundane matters and to the escalating violence of the War of Independence.

Conclusion

This essay has attempted to recover some of the realities of the pandemic of 1918/19 through the lens of the local newspapers. While these have limitations as a source – most notably their focus on the prominent, the sensational and the exceptional – their reports do convey something of the scale of the catastrophe as it affected the people of Co Wicklow. Sidelined for decades in the historical narrative, the epidemic’s centenary provided an impetus to scholarly debate and raised public consciousness of its severity, as well as prompting speculation as to the likelihood of a comparable event. Few, however, could have foreseen quite how soon our own experience would mirror that of our ancestors during that previous pandemic, the ‘summer scourge’, which became the dread disease of winter/spring 1918/19, with its monstrous legacy in terms of illness, death and disruption.

Sources:

Wicklow People and Wicklow Newsletter, June – July 1918; October 1918 – June 1919, accessed via https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/

General Register Office Civil Records https://www.irishgenealogy.ie/en/

Ida Milne, Stacking the coffin: influenza, war and revolution in Ireland, 1918-19, Manchester University Press, 2018.

Brother John Kavanagh, ‘The influenza epidemic of 1918 in Wicklow town and district’, Wicklow Historical Society Journal, 1990, http://www.countywicklowheritage.org/page/the_influenza_epidemic_of_1918_in_wicklow_town_and_district

‘Castletimon Heritage Trail’, https://visitwicklow.ie/item/castletimon-heritage-trail-brittas-bay/

Comments about this page

Poignant account of the great flu. The number of children who succumbed is particularly harrowing. Great research Rosemary.

Well done Rosemary! Yes, it does provide an echo, humbling our modern assumption of being beyond the reach of the microbe on such a scale.

Add a comment about this page