A Paper presented at the La Touche Legacy Seminar on Friday 26th September 2014

This paper is dedicated to Mary Brien, Biddy Whelan and Bridget Sherry of Bray and the thousands of other Wicklow women whose lives were changed forever by World War I

Historic Postcard showing Little Bray

War is a Men – Only Affair

On the 18th of August 1917 the Irish Times reported that a 45 year old woman, Margaret Farrell, appeared before a Scottish court and was fined the princely sum of one pound and one shilling for presenting herself at Glasgow Recruiting Office in male attire and asking to be enrolled in the Irish Guards. [1]

The message was loud and clear. War is a men-only affair.

Of course in practice that was far from the truth. The Irish and British men who went to the front left behind mothers and girlfriends, daughters and sisters. Women ran hospitals and charities for the fighting and injured. As the war progressed women populated factories and munitions works, mostly receiving lower pay than the men they replaced.

When 18 year old Ellen Capon appeared before the London courts in 1918, again discovered in a recruiting office committing the terrible offence of wearing male attire (trousers I presume!) her defence was that in order to receive a fair wage in the industry where she worked she had been obliged to dress as a man for two years.

The work of women throughout World War I, buoyed by the efforts of the Suffragette Movement, ultimately led in 1918 to the granting of voting rights for the women of Britain and Ireland. These voting rights were far from equal however.

The efforts of the men who fought in World War I were rewarded by a new reduced voting age of 19. The women however, many of whose lives were forever changed by the war, were given a vote, but only the women considered mature enough. The voting age introduced for women was 30 years and above.

It took the United Kingdom a full ten years to introduce equal voting rights for all in 1928. The new Irish Free State had passed them out six years earlier by granting equal suffrage to all of its citizens in 1922.

History would continue to give women the more silent role in World War I.

Remembering the War Dead in Bray

The War Memorial Cross in Bray

In 1919 when the beautiful Celtic Cross war-memorial designed by prominent architect Sir Thomas Deane was erected in Bray to honour the 168 local men who had lost their lives in the battles of World War 1, the Irish Builder magazine commented on the unusual phenomenon whereby one name in particular appeared to be so polished that it outshone the other names around it. [2]

The shining name belonged to Francis Sherry, son of Thomas and Bridget Sherry from Fassaroe. Today the name blends into the monument – it is no different in appearance to the other names around it. The exceptional shine observed in 1919 was therefore more likely to have been the result of a loving hand with a polishing cloth rather than some flaw in the metal.

Was it his mother Bridget or one of his three sisters, Mary-Ellen, Annie or 17 year old Stasia who maintained this silent shining vigil to his memory? For what other place did they have to visit? The grave of Francis Sherry is in France.[3]

There’s a striking piece of film footage on YouTube from Remembrance Day in 1924 showing the long procession of local people to that same war memorial in Bray, just ten years after the first casualties of World War I. [4]

Thousands of people thronged the Quinsborough Road, watching the marching bands and processions. This little film reminds us of how deeply and widely Bray was affected by the loss of these young men and also by the return of other men, sons, husbands, brothers and boyfriends many of whom would remain scarred physically and psychologically for life.

This type of procession was repeated in towns and villages throughout Wicklow and throughout Ireland.

When I watch the film of the procession down the Quinsborough Road I wonder if one of the young women in the smart hats is Biddy Whelan of Castle Street who lost her boyfriend Rifleman Jack Madden in 1914 or if I can pick out the face of Mrs Mary Brien of Ravenswell Row, mother of two names on the monument, Private Michael Brien who died in France in 1916, and Private Joseph Brien who against great odds almost survived the war until he too died during its last weeks in 1918. Mary Brien was also the aunt of Rifleman Phelim Brien.

The names of the three Brien cousins from 11 Ravenswell Row sit side by side on the Bray monument. For their families this was the only remaining connection with the lost men who just years before had been carefree boys playing on the back streets of Bray.

The Story of Biddy Whelan and Jack Madden

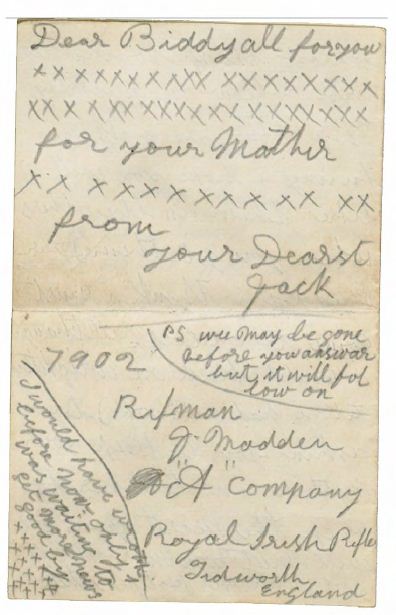

We know about Biddy Whelan because of the long love letter that her beau Jack Madden posted in August 1914 from Tidworth Camp in England, just days before he departed for France.[5]

Biddy was a 27 year old kitchen maid and lived with her widowed mother in a three roomed house on Castle St in Bray. I can’t tell you exactly where on the street it was but we know from the census returns that it had only two windows to the front which makes it a little easier to visualise.

The Whelans lived next door to the Browns, another family mentioned in the letter, and not too far away from where 25 year old Jack Madden lived with his father Justin, a baker, also living in Little Bray.

The love letter that Jack wrote to Biddy is held in the files of the National Archives. This first striking aspect to this correspondence is its length. Jack it seems was very love-struck indeed. Jack has only been gone from Bray for a little over a week -and very little has happened yet in military terms – but still the letter extends to 12 pages and includes 12 separate references to ‘dearest’ or ‘dear’ Biddy and a total of 66 kisses, 13 of which are for Biddy’s mother. Before the letter, Jack had already sent Biddy a telegram on departure to England from Belfast. Jack, as they say, had it bad.

But Jack’s letter also gives us an important insight into some of the varied reasons why young men joined the forces in 1914.

Sometimes it was to impress a young woman. Jack tells Biddy on page 3 of his letter:

“I took your advice. I went to my duty this morning and felt much happiness. Thanks to God.”

On page 4 he tells Biddy:

“I have made my army Will and you are my heir to anything I have to give. I have also made arrangements to send you one shilling per day while I am serving, that is to say every week you will receive 7 shillings out of my pay. You might as well have it and don’t work so hard while you get the money.”

Another motivation was money itself. Page 8 of the letter lets it slip that before joining up Jack had resorted to the pawn shop out of necessity.

“Dearest Biddy. I am sending you back the two pawn tickets. Biddy don’t think bad of me for doing so. When you get the money run into Dublin and see about it. Tell the man that I have gone to the front and I would not like to lose it. Biddy, for God’s sake don’t forget to see to them both. How I should be so unlucky as to have them in there? No matter, God is good and we will be together again.”

The letter is peppered with religious references. Jack asks Biddy to keep her mother in good spirits saying “tell her to keep the heart up as we will meet again with the help of God and his holy mother.”

This young man never once mentions the King or nationalism or any other political allegiance. His attachment is to his young woman and to his Roman Catholic upbringing.

It’s doubtful even that Jack went to war to see the world. He’s only gone a few days and hasn’t yet reached the front yet already he is writing:

“I miss my cup of tea and rasher.”

The love story between Jack and Biddy didn’t have a happy ending. On the 14th August 1914, just four days after the letter was posted, Jack landed in Rouen with his fellow members of the Royal Irish Rifles, 2nd Battalion. His war was to last less than ten weeks. By the time he got caught up in his last day of fighting on 27th October, his Battalion had lost practically all of its officers.

On day Jack died, only 46 men and two officers survived out of the group of 250 men and five remaining officers that had started out that morning. The day that Jack died was the first recorded date of the use of an early form of chemical warfare by the enemy. His body was never recovered.

Two months later on December 27th 1914 the Wicklow People newspaper reported that official news of the death of Private John Madden had been conveyed to his father Justin in Little Bray.

Less public record information is available about Jack’s bereaved girlfriend Biddy Whelan. We do know that the Army lost the record of Jack’s will but officials accepted the love letter as his intention that Biddy would be the heir to his property.

Sources tell me that Biddy later married and had her own family. However it’s hard not to believe that the loss of Jack Madden in such a brutal fashion wouldn’t have left its mark on Biddy throughout her life.

The Search for Mary’s son Private Brien

When I travelled to Ypres in Belgium earlier this year I knew that it would be impossible to visit the memorial places of all the Wicklow men that are known to be in Belgium.

I decided to find the Belgian buried sons of those Wicklow families whose mothers had lost more than one son to the war. There are actually four such families. Two are from Protestant religions and two are from Roman Catholic backgrounds. All came from relatively modest homes and each case the lost brothers died in different countries.[6]

One of the graves I was particularly keen to find belongs to Private Joseph Brien, son of Mary and Michael Brien from Ravenswell Row and later Green Park Road in Bray.

Anne Ferris standing next to the grave of Pvte Joe Brien at Dadizele Cemetery, Belgium

Joe Brien enlisted on St Patrick’s Day 1915, just five days after his 19th birthday. Nineteen was the minimum age for enlisting to go overseas.

This young man who had probably never travelled any further than Dublin on the train from Bray was immediately sent to fight in France.

His brother Michael was a year older and also joined up. Michael died first, in France in August 1916. By then the political scene in Ireland was changing. The execution of the 1916 Rising Leaders had hardened attitudes at home.

The world war which many had expected to end quickly was into its second year. Many soldiers and their families were beginning to question the sense of sending so many young men to their deaths on foreign battlefields.

For many of the young men the adventure was turning into a horror story, with their comrades and friends lying dead and wounded around them.

It is very clear from the military records[7] that Private Joseph Brien suffered a great deal during the war. He was hospitalised on at least four occasions, first with shellshock shortly after he arrived in France, later with physical injuries.

On one of these occasions, when suffering from a leg injury, he managed to be transferred to the Princess Patricia Hospital in Bray. It must have been a great relief for his parents to have him close by for that six week period in 1917.

Mary and Michael Brien were to see their son just once more before his death, when he returned to Bray on leave for a week in April 1918.

During that week of leave in 1918 there was an incident with a superior officer which ironically almost saved the life of Private Brien. It is easy to imagine the sense of frustration that this young man felt more three years into a senseless war that resulted in 16 million deaths and 20 million injured people.

The source of the dispute was not recorded but whatever the reason, Joe Brien struck this superior officer. In the official record it seems that the physical act was considered secondary to the offence of using insubordinate language.

Detention of Joseph Brien

We can only imagine what Joe said to the Officer. Private Brien was convicted before a military court and received a sentence of 12 months detention for his words and actions. Had he managed to serve that sentence he would have been spared from a worse fate.

Under these circumstances I am quite sure that Joe Brien’s mother Mary would have been pleased to see him in prison.

But Private Brien served just weeks of his prison sentence when he was suddenly released and compulsorily transferred from his Royal Irish Fusiliers regiment to a battalion of the North Irish Horse regiment fighting in Ypres. As it turned out, young Joe Brien had been handed a death sentence.

By all accounts the situation was pretty desperate in Ypres. According to the records, on the morning that Joe Brien was fatally wounded his battalion had no food. The army diary discloses that the men were sent out to fight in the cold without any breakfast because rations had become so depleted.

Joe Brien died of his wounds in Ypres on a cold day in early October 1918 barely a month before the end of the war. He is buried in a graveyard close to where he died.

Earlier this year I had the great honour of visiting Joe Brien’s grave[8] in a small well-tended cemetery of simple white gravestones just outside the beautiful town of Ypres.

Joe’s grave plot is at the boundary hedge of the cemetery, overlooking fields and countryside. He is buried under the shadow of a large lilac bush.

I left some heather from Co. Wicklow on Joe’s grave. Earlier that same day, in honour of all of the men from Co. Wicklow who died in World War I, I laid a wreath of Wicklow heather, handmade in Bray by local florist Anne Clarke, at the Island of Ireland Memorial Park in Messines.

It is unlikely that Joe Brien’s mother Mary ever received a similar opportunity to visit her son’s grave in Belgium or his brother’s grave in France.

In fact, Mrs Brien even had a struggle when it came to receiving the customary medals for her two sons.

It was Mary Brien who confronted the red tape and filled in the soulless bureaucratic forms that remain to this day on her son Joe’s military file.

It is in Mary Brien’s hand that we see a poignant note handwritten on the receipt she was asked to return for the ‘memorial scroll’ that the Army sent in her son Joe’s name:

“I have received no medals for either of my sons. M Brien.” [9]

Hand written note from Mrs O Brien at bottom of the signed receipt for her son’s ‘memorial roll’

These two Bray women, Mary Brien and Biddy Whelan represent hundreds of thousands of women throughout Ireland who were left to fill in the forms and pick up the pieces of the fragmented lives that resulted from World War I.

I am sure that these women would have become very confused at the subsequent disregard paid to their deceased and injured menfolk by generations to come.

Likewise, I am quite sure that Mary and Biddy and all of the other Irish women affected by World War I in this county would have taken pride in the level of remembrance and discussion and acceptance that this centenary year has inspired in Irish people.

The World War I Memorial at Woodenbridge

Woodenbridge Memorial Park Launch 18th September 2014

Last week as I stood at the memorial in Woodenbridge amongst the 1200 names from Co. Wicklow, most who never came home, I thought of the people they left behind. I thought of how proud Mary Brien and Biddy Whelan and Bridget Sherry would have been to see the names of their loved ones carved in Wicklow granite in such a beautiful setting.

The real value in all of this remembering is to ensure that history does not repeat itself during our future lifetimes. To do this effectively we must remember World War I from all perspectives, and that includes from the perspective of the hundreds of thousands of Irish women whose lives it affected.

Thank you

Credit is due to the staff of the Wicklow County Library Service whose work was of great assistance in the preparation of this paper. It was a privilege for me earlier this summer to be involved in the political process that led to the lifting of the recruitment moratorium in the library service to ensure the continuance of the much used Local History service.

[1] The Irish Times 18th August 1917

[2] The Irish Builder 22nd February 1919

[3] AWM145 Roll of Honour Cards 1914-1918

[4] British Pathe on YouTube, Celebrations at Bray 1924

[5] National Archives of Ireland NAI /2002/119

[6] Burrell Tom, The Wicklow War Dead, 2009

[7] British Army WWI Service Records www.ancestry.com

[8] IVF 26 Dadizele New British Cemetery, Belgium.

[9] British Army WWI Service Records www.ancestry.com

No Comments

Add a comment about this page