Kynoch's Arklow

Introduction

For over twenty three years Arklow was home to one of the largest munitions manufacturing facilities in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Here we attempt, with the support of acknowledged sources and Pat Power’s information boards to tell the story of this manufacturing facility called Kynoch’s in Arklow. It was an important and strategic manufacturer of munitions during the Boer War and subsequently during World War 1. We will also seek to explain why local mineral resources and facilities were of importance in the ongoing development of this commercial and military explosive manufacturing site.

This factory because of its size, strategic importance and employment had a lasting impact on the town of Arklow. The information boards erected at the Kynoch site greatly assist in deciphering what went on here.

Strategic Importance of Kynoch

Kynoch’s Arklow factory was responsible for all of the the company’s mining contracts south of the equator with the exception of Africa. The outbreak of the Boer war in 1899 led to the heavy demand for munitions manufactured in Arklow. Subsequently Kynoch’s was important in supplying munitions during World War 1.

The Boer war lasted from 1899 until 1902 and was fought between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (UK) and the South African Republic and the Orange Free State. Kynoch & Co. of Lion Works, Witton near Birmingham was founded by George Kynoch who started making explosives, in a small way in 1851. These explosives were used mainly for mining, quarrying, sports, munitions and railway development which was taking place throughout the UK in the 1800’s during the industrial revolution.

Why was a very large munitions factory located in Arklow.

The chairman of Kynoch was Arthur Chamberlain who was an uncle of the future British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. Because Arthur visited the Arklow area reputedly for leisure shooting purposes he was aware of the facilities at Arklow and presumably the fact that pyrite which is used in the manufacture of gunpowder was available at the Avoca mines. In 1891 a Liverpool Company contacted a solicitor called Buckett in Wicklow looking for a site for an explosives factory. Sandy land for purposes of setting up a munitions factory was purchased in Brittas Bay however, after local objections there, a Thomas Troy Chairman of the Arklow Town Commissioners promoted Arklow as a location for the proposed Kynoch Factory (Murphy 1976).

Many high profile people in Ireland became involved in the campaign to have the factory sited in Arklow including John Redmond leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, Father Dunphy, Lady Wicklow (Howard) of Shelton Abbey who was the site landowner. The Arklow site was chosen because it had a harbour, a sandy beach, a rail connection, the nearby town and an existing chemical factory; Hodgsons Arklow Chemical Works.

Kynoch won a contract in 1893 to manufacture a new explosive called cordite to supply the British Army (Mulvihill 2002). This came about because an engineer called Cocking approached Kynoch with a proposal for the manufacture of a new explosive called cordite which had been developed by Alfred Noble the inventor of dynamite. (History Ireland 2006). The building of the Kynoch facility in Arklow commenced in 1895 and it was to become one of the most complete explosive factories globally (Cocroft 2000). At one stage a the number of employees at Kynoch’s Arklow increased to almost 5,000 (Cannon 2006).

Interestingly Arthur Chamberlain, the chairman of Kynoch was the brother of Joseph Chamberlain a famous liberal politician who according to sources may have been involved politically in the planning of the Boer War as he was the Colonial Secretary. There were strong accusations of conflict of interest made in the newspapers at the time given the close relationship between the Colonial Secretary and Munitions manufacturer. According to sources Chamberlain wanted to locate a factory facility in Southern Ireland as an independent facility because he had a falling out with the Nobels who were also munitions manufacturers (Cocroft 2000).

Kynoch also bought the chemical works from Wicklow Copper Mining Company which was owned by Hodgson and which processed pyrites for the munitions process. Arthur was Chairman of Kynoch from 1888 until 1913. Kynoch Arklow success as a manufacturer of cordite lasted until 1907 when according to Cannon a batch of cordite was rejected by the British government for containing mercury which was prohibited. According to Arthur Chamberlain this may have been an act of sabotage, he said to Arthur Griffith that ‘it was a definite part of English policy to prevent any serious industrial or commercial development in Ireland’. After this the factory produced only industrial and sporting munitions from 1907 until the outbreak of the 1st World War when there was once again a “colossal demand for munitions on the western front” (Cannon 2006).

Explosives

Because of the local availability of pyrite Kynoch’s were able use this in the manufacturing of sulphuric acid which according to Morgan

“is the starting point of all chemical manufacture; it is the fundamental chemical , the first link in the chain of materials leading to the modern high explosive…..the war might be lost or won on the sole question of supplies of sulphuric acid”. The raw material from which this acid is extracted is called pyrite. The Avoca mines had an abundant supply of pyrite. A mechanism called the Herreshoff burner enabled Kynoch to avail of the local pyrites”.(Morgan 1916).

According to the Dictionary of Explosives the Kynoch factory manufactured blasting explosives from sulphur to make gunpowder, aphosite, aerolit, Bobbinite, gelatine, dynamite, gelignite and Kynite. Anchorite, Arkite, and Kynarkite which were coal mine explosives, were also made in Arklow. (Marshall 1920).

The Kynoch factory buildings

It is difficult to imagine now but the site of the Kynoch factory extended one and a half miles northward from the mouth of the Avoca River up the entire length of the north beach and beyond. It had its own gas works, electricity generator and tramway system (Cocroft 2000).

The electricity generated also served to provide public lighting according to Pat Power. The first house inside the gates was an office and laboratory. On each side of the entrance there were men and women’s dressing rooms. The women were engaged at packing and blending the cordite. There were several explosive drying sheds. In the sands close to the beach there were a number of magazine sheds. In the middle of the site there was a shed which was forty five yards long with several apartments for the final processing. Buildings had concrete foundations and corrugated sides and roofs, sheeted inside with timber.

On the northern part of the site there were three wooden houses which was where the nitro-glycerine was made. Embankments were built around sheds to absorb explosions at a distance of three feet and up to the eaves. The operators were known as ‘hill men’ because the houses they worked in were situated on high hills of sand. (Murphy 1976).

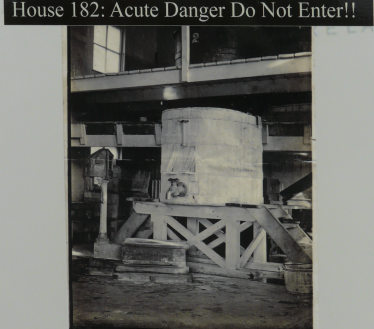

The processing houses were colour coded: ‘Danger Houses’ were painted red. Gun cotton drying houses were bright yellow. Storage magazines were bright blue. The nitro-glycerine house doors were always kept open when there were workers inside (Power 2013).

Transport within the Kynoch site

Sulphuric and nitric acids, made in the chemical works and were run through a lead pipe driven by compressed air and then transported by canal and then by tramway on tank bogies. The lake for the fire service was fed from a canal about six feet wide which ran from the chemical works to the end of the modern lake road (Power 2013).

Wooden dowels or trenells were used in the construction of boxes used to transport explosives. The finished process was packed and brought from the centre of the works along a tram track to the ball court lock which had been widened and deepened to enable small boats to transfer the material to the company’s steamers at the mouth of the bar to be shipped to the government magazines of Woolwick and Purfleet (Murphy 1976). The tramway was about 60 kilometers in length (Power 2013).

Kynoch applied to the Dublin Wicklow and Wexford Railway for an extension of the railway line to the chemical works. This line already carried ores from Avoca mines but the new proposal allowed for the rail to branch off at Ballyraine and end at the rear of the old coal yard on the quays towards the Chemical Works at the North Arklow Port.

Sea and Other Transport from Arklow

Knoch Arklow had streamers and sailing vessels entering and leaving on every tide. A new dock opened in 1910. Carters were in constant use carrying goods from the harbour to the town and to outlying districts. An overhead cable was erected across the river. Buckets capable of holding seven cwt. of goods such as coal and timber were attached to this conveyor belt system which constantly traversed the river. The Sth. Terminal stood near the old lifeboat house, about half way between the dock and the pier head. Between 1914 and 1918 Kynoch’s steamers crossed the Irish Sea 2,700 carrying 350k tonnes of cargo. According to History Ireland these steamers were named “Anglesea” and “Kynoch” (Cannon 2006).

In 1899 the Arklow plant was brought to a halt because the boat called ‘Anglesea’ became marooned behind a wall of silt. Later a dredger was bought. Chamberlain wanted the harbour to be approximately 13ft in low water as the sandbar in Arklow made it difficult for boats to come close to the harbour (Murphy 1976).

In 1920 according to the New York Times Feb 10th, thirteen large boxes of gelignite were stolen from a local drifter boat called “Dan O’Connell”. This weighed a half a ton and part of the sand hills were dug up and houses searched but no explosives were found.

Kynoch Impact on Arklow Town and People

The importance of the Kynoch facility to the war efforts meant that a very rigid social and commercial infrastructure was developed to facilitate the smooth running of this facility. This can be evidenced by the following steps which were taken which include:

- Employees were issued with exemption cards in case of conscription.

- Trains ran to Arklow from Wicklow, Rathdrum, Wexford, Enniscorthy Ferns, Camolin and Gorey.

- A train was employed on the branch line between Shillelagh and Woodenbridge picking up workers from these places and they travelled free.

- Armed police and British soldiers guarded the entrances to the plant.

- Families of coastguard men were ordered to vacate the coastguard premises so that soldiers could be accommodated there.

- Clogs were made locally because metal studded soles were not allowed. There is a road called Clogg Alley off Seaview Avenue which bears testiment to this practice. All danger houses had a number and this was marked on the workers shoes in non spark brass.

To all intents and purposes the entire town was placed under martial law for the duration of the war.

- Every publican in the town had to accommodate three soldiers each.

- Fishermen were affected by the arbitrary control of the Kynoch factory. They were not allowed to enter or leave the port in hours of darkness nor could they fish within five miles of the shore.

- By 1916 basic accommodation was provided for non-Arklow workers around the site. “the beds were never cold because as one set of men went on shift-work another came back to occupy their beds. The huts were so crowded that a rope was placed along one wall so that the men could hand on to it while sleeping on their feet.

- A garrison of 100 soldiers was brought in from Co. Cork to protect the factory.

- Local opening hours for pubs were restricted to 10am to 2pm and 5pm to 10pm.

- The Institute of Civil Engineers in London said that fumes from the factory had resulted in some men being incapacitated from further work owing to noxious gases’ The hospital had 900 reported injuries, many of which were burns inflicted by acid

(Cannon 2006).

At its peak Kynoch was said to have employed between 3,000 and 5,000 people. Unusually they employed several hundred women to work in the factory and they were considered exceptionally skilled in mixing Cordite paste by hand which had to be done in a very steady manner (Power 2013).

Blast in 1917

Local people still talk about the blast in 1917 when two hundred men and twelve girls were working the night shift. The blast threw townspeople from their beds and shattered windows, the noise was heard twelve miles away. Four huts each containing men mixing nitro-glycerine and guncotton had exploded. Three huts vanished completely leaving only a crater. They were taken to the factory’s small hospital. At the inquest the company manager Mr. Udal felt there could have been an attack from sea. A U boat had sunk a South Arklow light vessel on March 28th of that year just 6 months before the explosion in Kynoch’s. However, some weeks before the blast some workers had matches on them. A verdict of unknown causes was returned. Twenty seven men were killed that night.

In the end

“Several British explosives firms merged to form Nobel Industries, later ICI”. This included Kynoch Arklow and Ballincollig gunpowder mill was also part of this rationalisation. The Arklow site “was bought by the Hammond Lane Metal Company of Dublin which systematically scrapped the entire works”. (Mulvihill 2002).

What remains

The water tower in this area which is in the middle of a caravan site remains from the Kynoch factory compound also a wall from the electrical generating house.The current wild fowl lake used to be the dredged bed of the Avoca River which provided a reservoir for the fire service. During coastal storms, fragments of Kynoch material of stone, glass and metal are uncovered by the wave and tide action. Also storage magazines are still visible at low water (Power 2013).

The site had a social hall for the entertainment of important visitors it was called The Kynoch Lodge which remains on the site together with twelve houses built for workers (Cocroft 2000).

The base for one of Arklow’s earliest lifeboats built in 1856 purchased by the Mining Company in 1873 is still standing. In the Arklow cemetery an Irish Yew tree stands near the monument commemorating those killed in the Kynoch factory by the 1917 blast.

Kynock Heritage Walk

The Kynoch Heritage Walk commences at the Bridgewater Quayside entrance and continues along the North Quay towards the caravan park and concludes near the Arklow Bay Hotel. The total distance is approximately two kilometers. Along the route of this walk are six information panels, which brings to life the story of this huge explosive factory and the role it played in the history and development of Arklow Town (Arklow and District Chamber 2015).

Bibliography

Cannon, Anthony (2006). Arklow’s Explosive History – Kynoch. History Ireland. Available at: http://www.historyireland.com/20th-century-contemporary-history/arklows-explosive-history-kynoch-1895-1918/ Cannon, Anthony 2006.

Cocroft, Wayne, D. 2000, Dangerous Energy: the archaeology of gunpowder and military explosives manufacture. English Heritage.

Macrosty, Henry William. (2013). The Trust Movement in British Industry: A Study of Business Organisation. London: Forgotten Books. (Original work published 1907)

Marshall, Arthur.(1920) Dictionary of Explosives. Forgotten Books. 2013.

Morgan, Gilbert. T. 1916 Chemistry, The War and Ireland. Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 5, No. 17 (March 1916). pp. 32-43 Irish Province of the Society of Jesus.

Mulvihill, Mary. (2002). Ingenious Ireland. TownHouse & CountryHouse Ltd. Dublin.

Murphy, Hilary (1976). The Kynoch Era in Arklow. Arklow Historical Society. Wexford: The People Newspapers Limited.

Peters, Lisa. (2008). Hinks, J. & Armstrong C. eds. Welsh Obscurity to Notoriety – Lloyd George the Boer War and the North Wales Press. Oak Knoll Press and The British Library. Available at: http://chesterrep.openrepository.com/cdr/bitstream/10034/22512/8/peters-lloydgeorge08.pdf

Power, P. (2013) Information Boards for Kynoch Walk in Arklow.

Rees, J. (2004). Arklow the story of a Town. Wicklow: Dee-Jay Publications

Staffs Home Guard Website (2013). Misc. Information Kynoch Works Available at: http://www.staffshomeguard.co.uk/KOtherInformationKynoch.htm Company Part 1 from 1862-1960.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page