Baltinglass - The Coming of the Celts

Around 600 BC, a group of iron-using, war-like tribes, led by wealthy chiefs and speaking a common language, established themselves in central Europe. They were named by the Greeks, the Keltoi – the Celts. “Keltoi” may come from the ancient Gothic “to fight”.

Greek historians, who thought the Celts were a barbarous people, remarked on their drunkenness, their eagerness to strip for battle, their boastfulness in victory, despondency when defeated and their habit of nailing skulls of defeated enemies to their doorways. However, the Celts were also noted for their strength, courage, their skill in metalwork, particularly in gold, and their love of learning, whether in natural philosophy, religion or law.

The Celts spread from central Europe: west to Spain, east to Asia Minor, and north to Britain and Ireland. They made their way into Ireland by a series of invasions, from both the north and west, over a lengthy period, becoming thoroughly established by 150 BC at the latest. It is thought that they ruled over and then absorbed the people they found already dwelling in Ireland.

By 700 AD, Christianity had been a growing presence in Ireland for some three hundred years, creating a society which combined the pagan values of the ancient Celts with new Christian learning. This society was rural and tribal in character. It was a highly structured society, with marked degrees of status from slaves, through free farmers, up to high kings. There were no towns or villages. Nobles, farmers and their families lived in ringforts, known as raths. Some poorer people, such as herdsmen or slaves, lived in huts out in the fields. The combination of new learning and new farming techniques produced a distinctive Irish culture.

Farming

Yokes allowed the Celts to harness the pulling power of the ox. They put this to good use since it meant they could pull up tree-stumps from the fields, giving them a larger, more regular area to work in. Each field had a fence and covered one or two acres. The oxen also pulled a heavy metal-shod plough. The fact that the field was free from obstacles allowed the ox to pull in a straight line. The heavy plough bit deep into the soil.

Cereals were harvested by hand. A sickle was used, but unlike Neolithic times, the Celts’ tools had metal blades. This gave them a keener cutting edge, which could be resharpened when necessary. The corn was threshed with flails in a special barn. It was then winnowed to remove the husk from the edible grain.

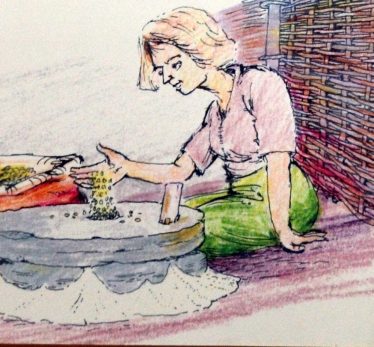

The rotary quern was a lot more efficient than the saddle quern. The upper stone had a hole bored in it so that the grain could be poured in. It was then rotated by a wooden handle, with the milled grain coming out at the edges. It was still hard and time-consuming work and it was a task often given to a female slave or “cumal”.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page