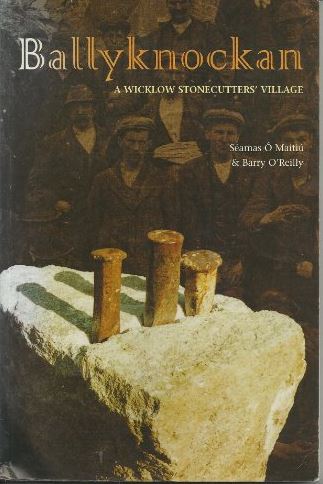

Ballyknockan

This article takes most of its information from a book called ‘Ballyknockan: A Wicklow Stonecutters’ Village’ by Séamas Ó Maitiú and Barry O’Reilly, (ISBN 0-9528453-5-0)

Multigenerational Stonecutting Heritage

Some tools from the early 19th century still survive today, as the spirit of Ballyknockans’ Stonecutting Heritage. Ballyknockan is on the western fringe of a massive band of granite that stretches south-west of Dublin Bay to County Carlow. As the popularity of granite as a building material increased the town then became a booming home to quarriers and stonemasons. In 1838, the Ordnance survey found that Ballyknockan employed 180 people, an incredible proportion of the town that barely reached a population of 400 by the mid-century.

Unusual location for an Unusual Town

The town was ideally located for the export of granite, as sourcing granite locally in Dublin was more costly than to import it. This led to many of Dublin’s’ leading architectural icons of the 19th century being made of mostly or in part Ballyknockan granite. But stone wasn’t the only export of Ballyknockan that received acclaim. A long and burgeoning tradition of stonecutting led to many Ballyknockans working abroad on Liverpool Chapel in Cornwall, but the granite ended up being too costly to import. Due to the town’s proximity to the Poulaphouca Reservoir, much of the town’s roads were effectively on floodplains, with a lot of the roads used for transporting quarried material being harsh bog roads. This was shown in the 1838 Ordinance Survey reports, which said that the two roads that went through Ballyknockan were ‘Both Bad’.

Unique Stone Architecture

The town possesses many characteristics that are unique because of its stonemason heritage. Most roofing of the cottages that remain from the 19th century is gabled, with some houses having converted to asbestos-concrete type slate covering from the traditional slate. The remarkable stonecutting skill that local craftsmen exported across the country can be still seen in the cottages they made and lived in. Beautiful half-door stonecutting that is seen in the most iconic Georgian architecture can be seen on Ballyknockan doors. Most Ballyknockan houses are direct entry which is characteristic of rural Wicklow housing. According to a local man, houses had a stone scribed or carved with a cross and set into the walls.

Pillars and Politics

It is hard to look at 19th century Georgian monuments in Dublin and not think of their political significance. The same can be said of the builders who built them. The rising of the Ideas of Parnell lead to a split in the community in the late 19th century, with a local brass band splitting up into a pro and anti-Parnell faction. Personal and Practical barriers existed to young men who wanted to enter the stone-cutting tradition. Firstly, many or most of the tools used were handed down and secondly, it was considered a very much familial tradition rather than a trade.

Land Grabber ‘Waterford’ and the Parnellite

Trouble had been brewing the small town of Ballyknockan between the Landlord, Lord Waterford, and his tenants. Lord Waterford’s main antagonist was T.M. O’Reilly, the Parnellite educated at Blackrock College and who became a journalist with the Kildare Observer and later with the Leinster Leader. Lord Waterford from his London club refused to agree to give out short leases to his Ballyknockan tenants meaning even if they had built their house, they did not own the land and could be evicted. The Landlord’s legal efforts against O’Reilly failed and the victory by the Ballyknockan community was celebrated by a bonfire in the hills.

Similar community initiative was shown in the face of poor pay and working conditions. The Stonecutters Union that was started in Cork gained great successes for the stonecutters of Ballyknockan.

After the second world war it was widely believed that granite was finished as far as the building trade was concerned with the introduction of reinforced concrete. This turned out to be the case and in the 1950s’ the large quarry closed down for some years. However, technology recently discovered that could slice the granite into slabs for cladding revived the trade. Cladding from this quarry was used in the building of the Central Bank and the Civic Offices.

Comments about this page

Link to a piece which I wrote with a Ballyknockan connection;

http://www.pencilstubs.com/magazine/MagPage.asp?NID=4788

Add a comment about this page