The Tragedy of Daniel Cunniam

Historian Dr. Emmett O’Byrne continues his new historical series focusing on ‘The Garden County’s’ past. In particular, Dr. O’Byrne will reflect on the more peculiar aspects of Wicklow’s history.(Wicklow People)

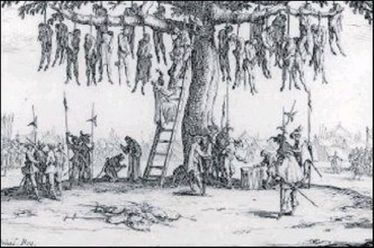

ONE of the most horrible events of the 1640s was the ordeal endured by Daniel Cunniam on Glenealy Bridge in early 1642, an act reported to Charles I of England. It is important to place Daniels’s ordeal firmly within its time, as it could be fairly said that the 1640s were an unparalleled age of atrocity in Ireland.

In late October 1641 rebellion broke in Ulster, spreading throughout the country.

In Wicklow (described ‘as the echo of Ulster’), the rebellion was led by the O’Byrnes and O’Tooles.

They were determined to tear the plantation of east and south Wicklow up by the roots, achieving it with considerable brutality.

Appalled by the vista of rebellion so close to Dublin, the lord justices dispatched Sir Charles Coote to Wicklow on 27 November. Coote was fearsome and thorough going, ransacking Wicklow town – putting men and women to the sword without distinction on 29 and 30 November before defeating the O’Tooles near Kilcoole on 1 December.

One of Coote’s lieutenants was a Scot named Lawrence Crawford (1611-1645), a colonel of a regiment of 600 men. Crawford was an experienced soldier, having served Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden.

He had been in Ireland a short time before the rebellion broke.

But he and his regiment were to acquire an extraordinary reputation for brutality.

For on hearing of Crawford’s approach in November 1641, the inhabitants of Bullock Co. Dublin took to their boats to escape him but were overtaken at sea and thrown overboard to drown.

In early 1642 Crawford was dispatched to Wicklow with orders to: ‘… slay and destroy all the rebels you can there find. You are in that county to destroy all rebels goods, houses, corn and to take their cattle’.

He executed his orders to the letter, as the journal of Captain William Tucker attests.

Tucker wrote ’20 January (1642/3) this day, Colonel Craford sic (Crawford) is come here with his party, who brought here with him above 5,000 sheep and 5 or 6 hundred cows., besides he killed of the enemy about one hundred’.

It was presumably then that Daniel Cunniam had the misfortune of encountering Crawford’s troops.

The story goes that one evening Daniel was crossing over old Glenealy bridge on his way home with a cartload of straw.

There he was stopped by soldiers under Captain Gee (sometimes described as Captain Rea) who demanded to know where a priest was hiding, accusing him of being rebel.

The accounts describe Daniel as being an old man, a freeholder and that he was not a rebel.

Indeed, he was held locally to be: ‘… very averse from the foul actions of the rascal multitude’. Yet, he refused to betray the priest, leading Gee to order his men to place him in stocks before putting his feet in the fire.

This ordeal went on for hours, as the papers say that the old man’s feet were reduced to ashes.

Even so, he refused to give information – dying there at the hands of his tormentors.

The horror was unprecedented even though atrocities were common.

In October 1642 Daniel’s ordeal was discussed at the General Assembly of Catholic Confederation at Kilkenny, forming part of the grievances presented to Charles I in 1643.

The memory of what happened was preserved by the publication of a pamphlet in 1662 in London.

It has also received attention from Thomas Leland’s History of Ireland (1773), while the great Daniel O’Connell also made mention of it in his Memoir of Ireland: Native and Saxon (1843).

Comments about this page

I found this article very interesting. While I had previously come across a reference to the killing of Daniel Cunniam I had not read the full details of his ordeal. You might be interested to know that another member of this family was to also suffer a horrific death during the Rebellion of 1798. I included an account of this event in my recently published book – Aghowle -Where The Divil Ate The Tinker. The account is as follows:

Extract from Aghowle- Where The Divil Ate The Tinker

Towards the end of 1797 the government launched a severe campaign to suppress the United Irishmen. To help the local Yeomen forces in Wicklow, militia units from other counties including Antrim and North Cork were drafted in and by April 1798 these forces were carrying out a widespread campaign of torture, house burnings, floggings and executions throughout the county. The following month saw an all-out rebellion throughout the country. The major battles and massacres from this period were well recorded and documented, but many of the small incidents throughout the countryside did not make the major headlines. However, in one publication titled Insurgent Wicklow 1798: The Story as Written by REV.BRO. LUKE CULLEN O.D.C. (1793-1859), we get details of many such incidents that took place throughout County Wicklow. Brother Luke Cullen gathered these accounts from local Wicklow people in the decades after the Rebellion, while they were still within their living memory.

1798 -Murders at Ballycullen and Aghowle

Insurgent Wicklow 1798 describes many atrocities that took place in Wicklow in local areas such as Newtownmountkennedy and around Killiskey. I was quite surprised to find that the townlands of Aghowle and Ballycullen also featured as places where torture, house burnings and murders had taken place at the hands of the Yeomen.

The following is a transcript from chapter four:

In the latter end of May ’98 a party of Wicklow local cavalry burned down the premises of Gregory Conyam(Cunniam), a farmer of Ballycullen (Ballincullen, S.W. of Rathnew). On their return, they met a man named Wn. Conyam of the same place. They hanged him (that is, they half hanged him, a term well known then, for half hanging and flogging generally succeeded each other) and burned straw under him to extract a confession and shot down his throat. (This Ballycullen is near Glanely and those men were of the same family of Mr. Danl. Conyam that Capt. Sir Charles Coote’s division roasted to death on the bridge of the latter place in 1641.

Hugh Magrath of the same place gave information on the following men in June, ’98 James Murphy, Thos Doyle, Matthew Cullen, Maurice Crane and Patrick Magrath, brother of the informer, all of Ballycullen. They were shot at their own places.

McDonnel McKitt of Munduff (near Ashford): his whole premises burned in May ’98: himself transported for 14 years. Luke Kelly of Ballinlea on the same day; his premises were burned. This was near Eccles of Cronroe. Wn. Pluck of Ballycullen; his place entirely burned and himself most barbarously used. (T.C.D. Mss)

Also in chapter 4 is the following account of what happened in Aghowle in December of 1798

A man named Harry Hetherington gave information to the Wicklow cavalry in Dec. ’98 that some men who had lately returned home from the mountains had formed a place of retreat in a large turf clamp at the residence of Wm. Murphy of Aghole (S. Of Ballycullen). To that place a party of the Wicklow Corps rode under the command of one of the Revels of Seapark and one of the Wrights of Dunganstown to the above place where they found Wm. Murphy and three sons- John, Patrick and David; the latter was an idiot. They met with him first and discharged some shots at him. He escaped their fire and ran to his mother for protection. She clasped her arms about him thinking that her maternal solicitude would protect him from their fury. But no, they clove open his head awhile in her arms. The shock to her intellect was terrific. She lost her reason that instant and exhibited her want of reason in the collection of the brains of her idiot son awhilst her husband and other sons were being butchered by her side.

The turf clamp was now assiled and Murtagh Doyle, Wm. Coffey, John Byrne, Garret Byrne and Garrett Vesty Byrne nine in all; after shooting them, they set fire to the clamp of turf, the house and every particle about the place.

The Cunniam family of Ballycullen were to remain living in the locality for another 200 years and the last member of this family, Gregory Cunniam, is still well remembered in the locality.

Add a comment about this page