The Impact of World War One on the Dunlavin region by Chris Lawlor

Many of the inhabitants of Dunlavin were probably quite unmoved when Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on 28 July 1914. There had been crises in the Balkans before, some of them very recent. In common with people in many other European villages, most people in Dunlavin probably thought that a major continental conflict could be avoided this time too. However, on 4 August Britain declared war on Germany, meaning that Ireland was also among the belligerents from that point onwards. Dunlavin was a village with a long military tradition. Its proximity to the Kildare border meant that it had links to military bases in that county such as Naas, Newbridge and the Curragh. Commercial links existed with these army bases and Dunlavin merchants traded with them.[1] The village was also a stopping-off point for the military en route to their camp in the Glen of Imaal. Army horses were often seen drinking at the village pump outside Fisher’s public house, while soldiers rested on their march and officers quenched their thirst inside the premises. The enterprising Mr Fisher could not charge the army for the water, but he did rent them the buckets to use when watering the horses.[2]

“All over by Christmas”

Generally, the war was greeted enthusiastically in Dunlavin and throughout west Wicklow. Many people on both sides thought that the war would be ‘all over by Christmas’, and the outbreak of war precipitated a flood of volunteers into Lord Kitchener’s new army,[3] who joined up for a variety of reasons. It was unsurprising that Dunlavin’s Church of Ireland, predominantly Unionist, population supported the call to arms, but there was also another Dunlavin response to the declaration of war in 1914. Most of the nationalist community in the village also supported the war effort, and many members of nationalist families enlisted, especially after the Home Rule Party’s leader, John Redmond, spoke at Woodenbridge in September, calling on all members of the Irish National Volunteers, to join the British army and to go ‘where the fighting line extends in defence of right, of freedom and of religion in this war’.[4] The vast majority of the Volunteers followed Redmond, and large numbers of them were recruited. There can be little doubt that many young Dunlavin men joined up with a sense of adventure, perhaps seeking to escape the mundane banality of the commonplace in a quiet little village with limited economic opportunities and a monotonous social life. There can also be little doubt that for many the army offered an escape from either temporary or permanent unemployment, under-employment and poverty by providing a regular wage.[5] However, another, often (possibly deliberately) overlooked motive for the positive Nationalist response to World War One exists. Many of these men probably genuinely believed that German militarism needed to be stopped in its tracks. Contemporary media propaganda probably affected their decision, but the unprovoked invasion of neutral Belgium, and accounts of German atrocities in that country, persuaded many Nationalists that they were doing the right thing in going to war to save ‘little Catholic Belgium’.[6] For all kinds of reasons, Dunlavin recruits joined up at local military depots, one of the closest of which was at Naas, which acted as a recruiting centre for west Wicklow as well as for county Kildare. Although the whole Naas electoral division’s population stood at a mere 4,317 people in 1911,[7] by June 1917, over twenty-two and a half thousand volunteers had enlisted in the town,[8] many of them coming from villages in its hinterland such as Dunlavin.

Financial support

The reality of war elicited a rapid response in Dunlavin, as people rallied to support the cause financially. In August 1914 the Prince of Wales set up a national relief fund in aid of the war effort. Monies collected were to be distributed to military widows and orphans, to help wounded soldiers returning from the war and to pay for medical treatment of the wives and children of soldiers away at the front.[9] By mid-September, Dunlavin’s Church of Ireland congregation had collected £6 10s, sent in by Rev. H Acheson, and Mrs. Tynte of Tynte Park House had subscribed the third-largest amount on a published list of county Wicklow donations.[10] Despite strong support for the war effort casualties mounted and it was soon evident that the conflict would not be ‘all over by Christmas’. As that feast approached, the British Red Cross Society held a meeting in Baltinglass, where Lady Powerscourt, the president of the society in county Wicklow, announced that a county Wicklow ward for wounded soldiers was to be opened in Sir Patrick Duns’ Hospital in Dublin. She asked for a generous response to the appeal and was sure that the Baltinglass district, which included Dunlavin, would rise to meet the challenge.[11]

Local effects

Many aspects of everyday life changed in 1915 as it became obvious that the Great War had become a stalemate and the war effort would be a protracted one. In January the Baltinglass Board of Guardians discussed supporting the Red Cross appeal for the Wicklow ward in Sir Patrick Duns’ and providing blankets for Belgian refugees.[12] An unforeseen result of the war surfaced in February, when complaints were made about the state of the road from Dunlavin to the Glen of Imaal, which was badly damaged due to increased heavy military traffic. The County Surveyor was authorised to spend £350 on repairs.[13] A court case in May attracted a lot of attention when Murtha Nolan of Fauna as charged with treason at Dunlavin Petty Sessions under the Defence of the Realm Act. Nolan had spoken against the King and told some soldiers that ‘it was the Kaiser’s uniform they should be wearing’. The defendant claimed he was drunk at the time and apologised for his comments. The magistrates underlined the seriousness of the case and made it clear that Nolan could face the death penalty or penal servitude for life. In the event, however, they were inclined to clemency and sentenced Nolan to a mere two months imprisonment with hard labour.[14] On the other side of the coin, in August, Michael Neill was only given a nominal fine by the Dunlavin magistrates for being drunk and disorderly when they heard that the army had rejected him as a recruit and he was ‘annoyed because he could not fight for his country’.[15] As the year 1915 drew to a close an auction was held in aid of the Dunlavin Red Cross fund in December.[16] Evidently, casualties were continuing to mount was the war rumbled on.

Continued support for the troops was needed in 1916, and in April a flag day in Dunlavin raised £11 2s 6d for the Countess of Wicklow’s fund for the Royal Dublin Fusiliers. The countess wrote from London, thanking all who contributed and saying that she knew the ‘people of county Wicklow would not be ungenerous in their contribution to the comforts of this gallant regiment’.[17] Despite gallantry, the army had its share of deserters, and in August a Dunlavin man, Christopher Kehoe (formerly of the 3rd Battalion, Royal Dublin Fusiliers but transferred to the 4th Battalion, Royal Irish Rifles), was arrested in Hacketstown and charged with desertion. Kehoe told the resident magistrate, J. C. Ryan, that he had been stationed at the Pigeon House fort, but had run away from the sergeant in charge of him. Ryan ordered Kehoe to be handed over to the military authorities. The prisoner was remanded in custody until a military escort arrived to accompany him back to Dublin.[18] The war also increased workloads for many people, and in December 1916 three employees of the Baltinglass Board of Guardians, Messrs. Whelan, Lalor and Kenny, were granted a war bonus of 3s extra per week, payable from 1 January 1917. The motion was passed by the board even though the chairman dissented, and 1917 began with the continuing war looming large in people’s lives and no end in sight.

Food shortages

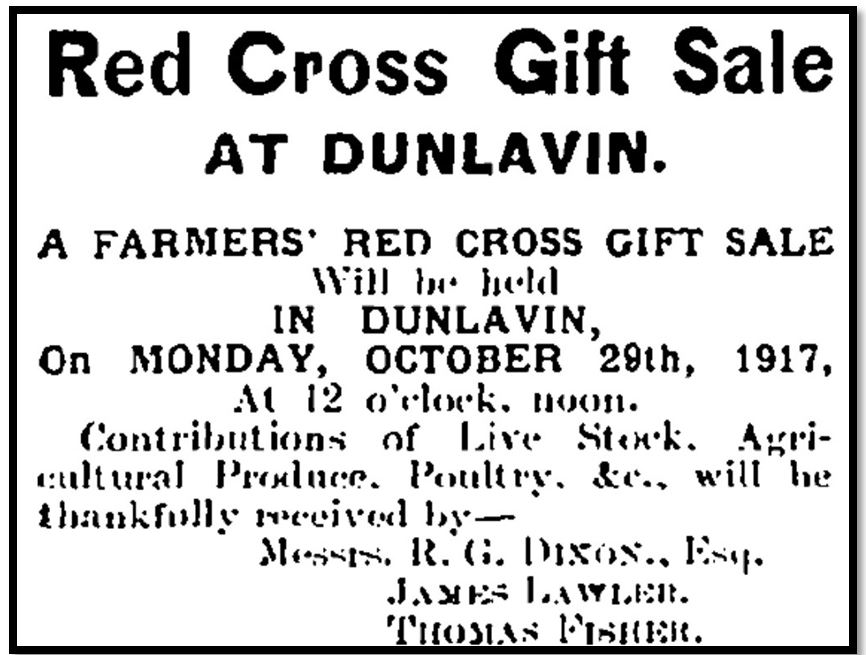

As the year 1917 opened, food was in short supply in the belligerent nations, and a new food production scheme was introduced in Ireland. A meeting was held in Dunlavin national school to ‘consider the provisions of the scheme’ in February. The list of those present included leading members of both religious communities in the village. Evidently the new scheme would affect all food producers, irrespective of their creed. The meeting decided to ask the Government and Food Controller to fix the price of oats, to ask the Department of Agriculture to supply the district with a tractor and plough at a reasonable rent and (unlike Baltinglass) not to have allotments for food production rented above the poor law valuation.[19] Meanwhile, fundraising had to continue and another auction was held in the village for the Red Cross fund in October 1917. The war ended in 1918, but not before a final fundraiser was held in Dunlavin, when a mixed doubles American tennis tournament was held at Tynte Park in July with the proceeds going to war funds. All monies for this event were collected by the local Church of Ireland rector, Rev. H. Acheson.

Fig. 1: Advertisement for Red Cross auction in Dunlavin. Source: Leinster Leader, 20 October 1917.

Dunlavin war-dead

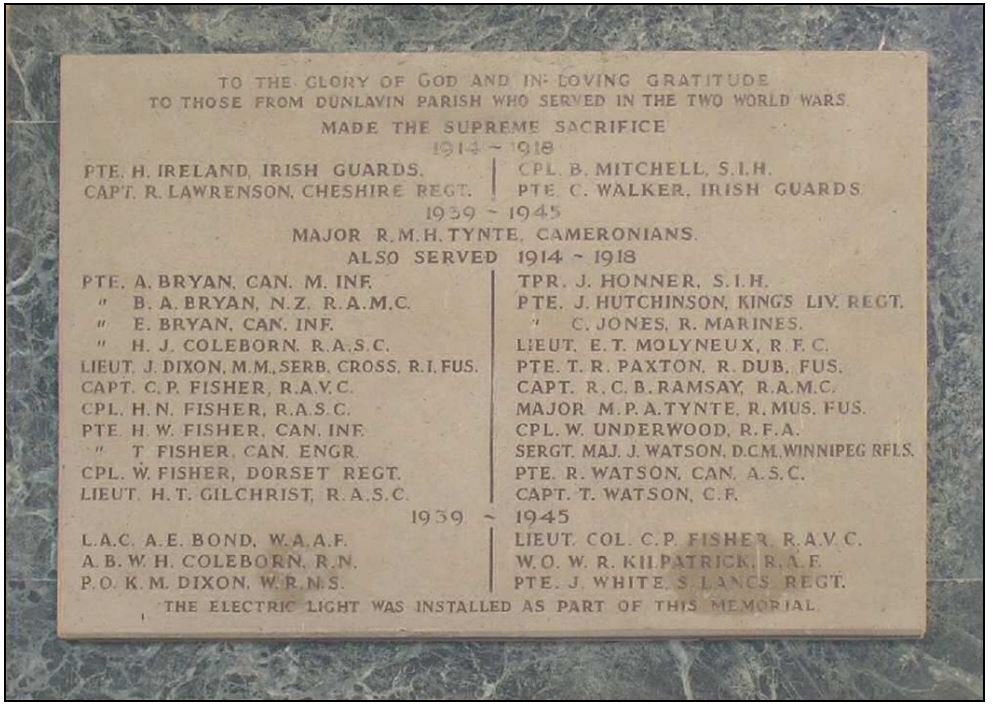

A wall tablet in St. Nicholas’ church, Dunlavin attests to how well the village’s Church of Ireland community answered the call to arms. Twenty-three names, including members of leading local Protestant families such as Tynte, Fisher, Molyneux and Dixon, appear thereon as having served during the Great War. Four of the names on the plaque, those of Private H. Ireland, Captain R. Lawrenson, Corporal B. Mitchell and Private C. Walker, are inscribed as having given the supreme sacrifice. However, none of these names appear with Dunlavin connections on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website.[20] The only Private H. Ireland listed for the Irish Guards is Henry Ireland of 1st Battalion, Irish Guards who died on 18 May 1915 at the age of 22. He was born in Shillelagh and was the son of Henry and Sarah Ireland, of Whaley Abbey, Rathdrum. Only one Corporal B. Mitchell is listed. He was a member of the 11th Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment, not the South Irish Horse. The only Private C. Walker listed for the Irish Guards is Christopher Walker, a member of the 2nd Battalion, Irish Guards who died on 24 April 1918, aged 28. He was the son of Robert and Anne Maria Walker, of Carrane, Tubbercurry, Co. Sligo.[21] One Lieutenant Raymond Fitzmaurice Lawrenson of the Cheshire Regiment, who died on Wednesday 5 September 1917 at 27 years of age, is listed on a separate website.[22] Henry Underwood, who was born in Dunlavin, also made the ultimate sacrifice. Underwood, attached to the Connaught Rangers 1st Battalion, lost his life in Mesopotamia on 7 May 1916. He is interred in the Amara war cemetery in Iraq.[23] It is possible that some of the others named on the plaque were born in Dunlavin but no longer lived there, or were related or known to members of the Dunlavin congregation, and so remembered in the church.

Figure 2. War memorial in St. Nicholas’ church, Dunlavin. Source: photo taken by the author.

Many Dunlavin Catholics also gave their lives, fighting as nationalists in support of Home Rule, in addition to fighting against the Kaiser’s Germany for other reasons. Men such as Private James Christie of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, who was killed at Gallipoli on 29 August 1915, Sergeant Philip Nolan of the Irish Guards, who died near Ypres on 20 June 1916 and Private Michael O’Neill of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, who lost his life in the Bailleul area of northern France on 18 March 1917, were all members of nationalist families from Dunlavin.[24] Significantly, unlike their Protestant counterparts, these men, who soldiered in Flanders fields and further afield, have no memorial in the village, as subsequent events changed nationalist mindsets in later decades. Another soldier with links to Dunlavin who was killed during the years of the Great War was Captain Alfred Warmington, whose father Alfred senior of Naas had supervised the operations of the Munster and Leinster Bank in Dunlavin in the late nineteenth century.[25] Warmington was shot dead in the attack on the rebel-held South Dublin Union on the afternoon of Easter Monday 1916.[26] The Easter Rising and its aftermath was to change Irish nationalist perceptions of the whole political situation, suppressing the memory of those from Dunlavin and elsewhere in Ireland who fought in the war to end all wars. It would be almost a century before their memory was reclaimed.

Endnotes

[1] Army W.O. Form 1452, C. Ward, Paymaster’s Office, Curragh Camp to Martin Kelly, 12 November 1872 and other documents in the possession of the author. I wish to place on record my thanks to the late Tommy Swaine, who provided me with these documents.

[2] Oral tradition. I am indebted to the late Gerard O’Dwyer for this information, which was subsequently confirmed to me by other residents of the Dunlavin area.

[3] Tom Johnstone, Orange, green and khaki (Dublin, 1992), p. 12.

[4] Freeman’s Journal, 21 Sep 1914.

[5] The Nationalist and Leinster Times, 13 Nov 1915 reported on a recruiting meeting held in Baltinglass, observing that ‘The recruiting agents have had a rich harvest in west Wicklow, especially among the working classes’. The situation in county Kildare was similar. James Durney, Far from the short grass: the story of Kildare men in two world wars (Naas, 1999), p. 4.

[6] This is the position taken in relation to Redmond’s Woodenbridge speech and the response to it in John Bruton, ‘September 1914: John Redmond at Woodenbridge’ in Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, vol 101, no. 402 (Dublin, Summer 2012), pp 237-241.

[7] http://airo.maynoothuniversity.ie/external-content/population-change-1841-2002-kildare (visited on 12 Oct 2019)

[8] Durney, Far from the short grass, p. 9.

[9] https://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/national-relief-fund-reaches-26m-mark (visited on 6 Mar 2018)

[10] Wicklow News-Letter, 19 Sep 1914. Mrs Tynte donated £3.

[11] Nationalist and Leinster Times, 19 Dec 1914.

[12] Nationalist and Leinster Times, 16 Jan 1915.

[13] Leinster Leader, 20 Feb 1915.

[14] Kildare Observer, 22 May 1915.

[15] Leinster Leader, 28 Aug 1915. However, Neill may have joined up later on, as a Michael O’Neill from Dunlavin was killed in action in 1917. It is probable that this was the same man.

[16] Leinster Leader, 27 Nov 1915.

[17] Nationalist and Leinster Times, 8 Apr 1916.

[18] Nationalist and Leinster Times, 5 Aug 1916.

[19] Leinster Leader, 03 Feb 1917.

[20] This searchable database is available at https://www.cwgc.org/

[21] https://www.cwgc.org/ (visited on various dates).

[22] https://astreetnearyou.org/person/255852/Lieutenant-Raymond-Fitzmaurice-Lawrenson (visited on 12 Apr 2019).

[23] Tom and Seamus Burnell, The Wicklow war dead: a history of the casualties of the world wars (Dublin, 2009), p. 293.

[24] Ibid, pp 54, 232 and 239. Burnell and Burnell list sixteen men with direct family links to the Dunlavin-Usk-Colbinstown area who lost their lives in World War One. Even a brief surname analysis suggests that many came from Catholic, nationalist families. The surnames and page references are as follows: Allen [13], Byrne [38], Cahill [49], Christie [54], Coleman [58], Cullen [68], Ennis [100], Ghent [117], Harman [132], Keating [157], Lennon [182], Nolan [232], O’Neill [239], Riordan [260], Tynte [287], Underwood [293] and Whyte [306]. Very many other nationalists, from all over west Wicklow, are also listed in this work.

[25] Leinster Leader, 22 Mar 1890.

[26] http://www.kildare.ie/ehistory/index.php/forgotten-fatality-of-the-rising-naas-officer-killed-on-easter-monday/ (visited 3 Sep 2017) and https://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/chronology-of-the-easter-rising (visited on 17 Feb 2018).

Comments about this page

The five Fishers and one Molyneux are all members of my mother’s family. She was the daughter of Lt Col CP Fisher, RAVC, MRCVS and niece of Harold Fisher.

The Fisher referred to is my greatgrandfather Thomas Fisher (1859-1939). His elder son, Harold, served in WWI, and his younger son, Claude Percy (my grandfather), in both World Wars, with a long stint in the Sudan government in between. I’ve heard the story of the buckets from my mother’s first cousin, Harold (only son of the above). Apparently, when people complained he was ‘selling’ the water, his answer was ‘I’m not selling the water, I’m renting the buckets’.

Add a comment about this page