Introduction

The Miners’ Way is a way-marked trail launched on 7th June 2019, The trail encompasses three valleys; starting at Glendasan, continuing to the Glendalough and finishes at Glenmalure. It is approximately 19km in length and takes in the remains of old mine workings, processing plants and touches upon the rich mining heritage of the area. The information in this article is taken from a map guide that can be picked up in local outlets at Glendalough, Laragh and Glenmalure.

The three valleys were formed during the Ice Age approximately 20,000 years ago which helped to sculpture the U-shaped glacial valleys we see today and the two lakes in Glendalough. Millions of years ago the collision of the continental plates resulted in the formation of the Wicklow Mountains into a large granite mass. As the granite eventually cooled, cracks appeared which became filled with the hot fluids creating various minerals. Cooling and chemical reactions caused metal ores to be deposited as veins in the cracks. In the Wicklow Mountains, lead and zinc are the main ores to be found, although small quantities of silver were also extracted from the lead ore.

The earliest documented lead mine in operation in Co. Wicklow was at Ballinafunshoge in Glenmalure. It was discovered in 1726 and mining work began as early as 1783. Mining in the other valleys dates back to the turn of the nineteenth century when the Government commissioned a survey of gold in County Wicklow not long after the 1798 rebellion. A rich vein of lead ore was discovered in the Glendasan valley. Over the course of 150 years the exploration of mineral deposits was extended over the three valleys with mine sites and processing plants established in Glendasan at Luganure, Ruplagh, Hero, Fox Rock and Molly Doyle; in Glendalough at the Miners’ Village, Van Diemen’s Land Mine and in Glenmalure at Ballinafunshoge, Ballinagoneen and Baravore.

There are six interpretive panels with further information at each of the key mine sites along the route.

Miners’ Way Trail

Glendasan

The earliest phase of mining dating from 1807 was at Luganure. The price of lead on the open market was always a factor in the running of the mines. Price fluctuations meant that wages also varied over time; typical of the boom and bust characteristic of the industry.

When times were good the Mining Company of Ireland prospered and invested in buildings, equipment and machinery. A rode to the Luganure ore body was constructed in 1826 and a railway track for wagons 126 feet into the mine was also laid. Dressing floors for separating the ore were built on the site and the Hero Mine was then opened, followed by the Fox Rock Mine in 1828.

Over the next 10 years machines for pumping out water from various mines were installed so that mining work could continue. Many of these were powered by mules that were later replaced by water powered machines that also drove crushing mills on site.

The Ruplagh Mine and new pump house opened in 1835.

The 1850s saw a big improvements in lead prices and a new wave of investment followed with old workings being re-opened and a new crushing mill installed supported by other new machinery. A new forge was built in the 1870S which saw further technological advances responsible for reduction in labour and wages. This meant in some cases two of three boys could now do the work of nine men.

The 1880s saw a major decline in the fortunes of the Mining Company of Ireland which had sustained losses over several years. Their business risks were compounded by falling lead prices and limited lead reserves and in 1890 the mines were bought by the Wynne family.

The Wynne family soon ran into difficulties with flooding and lack of machinery and after a few years mining came to a halt. The demand for lead during the years of WW1 brought the ‘Glendalough Mines’ to the attention of the Ministry of Munitions in London which granted aid to the Wynnes to re-open the Fox Rock mines in Glendasan.

For over 20 years there was no mining until St. Kevin’s Lead and Zinc Mine was set up in 1948. A workforce of 80 operated it for nine years some of them living in dwellings in the north and south sides of the valley, the remains of which are still visible including Fiddlers’ Row where it is reputed all inhabitants were musicians. The two main tunnels in the 1950s were the Fox Rock and the Mill Doyle. Work in the tunnels was difficult because of flooding and poor ventilation and as a result many miners developed health problems.

1950s ore bogie Glendasan Mine

Lack of money continued to be a problem for St. Kevin’s Lead and Zinc Mine. While sufficient ore was found the company did not have the technology to process it and as a result a Canadian mining company leased the mines from the Wynnes in 1956.

Glendasan Valley from Glendasan Mine

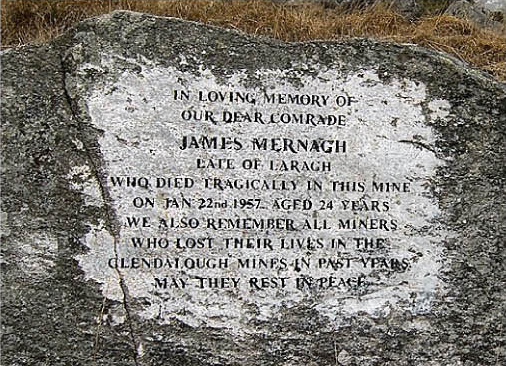

Given that mining is a hazardous activity it is remarkable that there were only three recorded fatalities over the 150-year lifetime of the mines. Over 80 years passed unil the final fatality occurred on 22nd January 1957. Two miners were drilling into the rock when the drill inadvertently struck a piece of dynamite and an explosion occurred. Jim Mernagh, a married man with two young children, was killed instantly and his co-worker, Robert Carter, was seriously injured. Thankfully Robert recovered from his injuries. He has since devoted his life to the preservation of the mining heritage of the area and has been a leading light in the development of this mining trail.

The Canadian Mining Company, which had taken over the mines in 1956, was not successful in locating the expected amount of lead and this, along with the fatal accident, was tha main reason the mines finally closed in June 1957.

James Mernagh Mamorial, Foxrock Mine

Glendalough

The Camaderry Mountain separates the two valleys of Glendasan and Glendalough and their associated mines and processing plants. The Luganure mineral vein cuts across the Camaderry Mountain and the workings in the two valleys were connected by tunnels and shafts with a slope towards the Glendalough valley to aid draining and movement of ore by gravity to the processing works in the Glendalough valley known as the Miners’ Village. The term Miners’ Village is a misnomer as it is unlikely any miners lived in the area except for a caretaker or non-permanent workers.

Rolling Crushing Mill, The Miners’ Village, Glendalough

Exploration work started in the Glendalough Valley in the 1850s with the construction of a second set of buildings including a waterwheel house and crushing mill.

Workings further up the Glendalough valley were developed and these upper reaches of the valley were aptly named Van Diemen’s Land by the miners because it seemed so far away from civilisation.

The 1860S saw the Mining Company of Ireland (MCI) build a school for the miner’ children whose purpose was to provide ‘good efficient company servants’.

Illustration of The Miners’ Village in the 1800s

Mules were initially used to carry materials up the steep mountain side and bring the ore down. This was later replaced by an inclined railway which resulted in greater efficiency and productivity. Although mining in this valley only lasted for approximately 20 years, the mined lead continued to be processed here into the 1900s.

Mining operations were becoming increasingly limited from the early 1880s onwards and there are records of sheep being brought in to graze on MCI lands in 1883-84 in an attempt to make some money out of the land. The lease on the surface land belonging to the MCI was sold in 1889 for “forestry, sheep and rabbits”.

Reworking of existing waste tips continued for a few years after mining ceased but by 1900 all production of ore had stopped.

Miners’ Village, Glendalough, from the Spinc

It is likely that with end of mining at the site any items of value would have been taken away, though there may have been some delay while there were still hopes of restarting the mines. Portable material such as roof slates and timbers may have been carried away for use elsewhere, speeding up the process of decay of the buildings.

Before the outbreak of WW1 in 1913 new machinery was imported on to the site to crash and extract further ore form the existing spoil heaps. As far as can be established water was still required for washing and separation functions and driving machinery and the main spoil heaps seen today date from this time.

From the 1920s the processing plant included a large timber shed which would have enclosed machinery but this was destroyed in a severe storm in 1935 resulting in the site being finally abandoned, thus ending the industrial age in the Glendalough Valley.

View towards Van Diemens’ Land from The Miners’ Village

Glenmalure

The main mining centres in Glenmalure were at Ballinafunshoge, Ballinagoneen, and Baravore. Ballinafunshoge Mine was the earliest mine in operation in Co. Wicklow, and was the most productive mine in Glenmalure.

The Miners’ Way, Glen Road, Glenmalure

From Glendalough the Miners’ Way follows part of the Spinc trail, joining the Wicklow Way and finally descends into the Glenmalure valley, via an old mining donkey trail. This trail was used to bring peat to the Smelting House at Billinafunshoge Mine beside the Mill Brook waterfall. The track down to Ballinafunshoge is lined in part by dry stone walls dating from the mining area. Scots pine trees still line this path and were first planted in the area by the mining companies to provide pit prop, building floors, joists and leat trestles for the mine sites.

Lead mining began at Ballinafunshoge in the late 1700s and continued to operate in a “boom and bust” pattern through to the end of the 19th century.

The furnace and chimney of the smelting house at Ballinafunshoge would have been a prominent freature in the area. However, all that now remains is a stone wall built into the bank near the Mill Brook at the Ballinafunshoge Recreation Area. It is reported that, during the 1798 Rebellion, rebels stole timber from the roof of the smelting house to repair the handles of their pikes. This building was later used as an office for the mines and also accommodated some mining families.

Smelting House, Ballinafunshoge Glenmalure (Image courtesy of National Library of Ireland)

Whilst at Smelting House are it is worth reflecting on the well documented tragedy that occurred here on the 23rd March 1867 when a landslide washed away a miners’ cottage resulting in the loss of two children.

Approximately 30 miners moved into the area to work in Ballinafunshoge Mines accompanied by their families. The miners built a school nearby which was opened in 1836 with 70 children enrolled. The ruin of this small building can be seen by the roadside beyond the spoil heaps. There were two periods of instruction in the school day to facilitate the children who were working in the mine. The school remained open until March 1875 when mining went into decline in the valley.

In the forest on the opposite side of the Glen Road following the Miners’ Way, lies the remains of the old crushing and grinding plant which was powered by a waterwheel, fed by leats from the nearby Mill Brook. A railway system operated at Ballinafunshoge to bring the lead to the surface in ore carts. These wagons were also used to transport tourists underground to visit the chambers of them mines circa 1822. A cast iron wheel from one of the wagons was discovered on the spoil heaps in 2014.

Many local place names date back to the mining era e.g.; the Schoolhouse Bank, the Flooring Bank, the Mill Bank and the Smelting House Bank.

Crushed House, Baravore, after restoration in 2017

The Miners’ Way continues along the Glen Road passing the 1798 memorial at the car park and crossing the footbridge into the townland of Baravore. In 1851, 278 people lived in Baravore in small dwellings, built by the mining company. Local folklore claims that 100 lights were carried across the paved ford in the River Avonbeg as mining families made their way to church services on Christmas mornings.

The Miners’ Way Trail ends at the New Crusher House which is the best extant example of a 19th century rolls crusher house in Ireland. At 11.10m in height, its consolidation in 2016 under the BHIS Scheme coordinated by Wicklow County Council and funded by Coillte and the Department of Culture, Heritage and Gaeltacht, was a challenging project. That same year the Crusher House was selected by the National Heritage Council for inclusion in their first “Adopt A Monument Scheme”.

As part of the programme of works in the area, Collite has developed the Heritage Looped Trail which links this site to old mine workings and buildings on the hillside. The looped trail passes the Historic Hostel once owned by Maud Gonne McBride and bequeathed to An Oige by Dr Kathleen Lynn in 1955.

Acknowledgments

This map is produced by the Miners’ Way Committee under funding provided by the Department of Rural and Community Development with support and inputs from local interest groups including the Glenmalure PURE Mile Community Group, Glens of Lead, Wicklow Upland Council, PURE Project, Friends of Glenmalure Hostel, and the Glendalough Mining Heritage Committee. Their aim is to record, present, preserve and highlight the unique mining and social history of the areas that spans two centuries.

Health and Safety notice for Walkers

The estimated time to complete the walk is 6 hours.

Please stay in the way-marked trail that is marked with arrows and miners’ icon. ![]()

The trail is set in the beautiful valleys and uplands of the Wicklow Mountains and due to the terrain the walk is classified as strenuous. Some sections have steep climbs over rough ground requiring walkers to be accustomed to walking and high levels of fitness. Specific outdoor walking footwear and clothing id required.

There are no places on the route where food and refreshments can be purchesed. Take enough water and food to meet your needs.

The walk should be completed in day light hours.

Mobile phone coverage is variable but we recommend a phone be taken. In case of emergency dial 999 or 112.

Comments about this page

Thanks for the positive feedback Mary. Yes the information gathered, and the resulting trail is the result of years of research, mostly driven by the local communities in the Glendalough, Laragh and Glenmalure areas. It is a fascinating and unique part of Wicklow’s heritage, and a stunning (though long!) walk.

This is a powerful, well researched and (in my opinion) really important gathering of facts and gives the mining operations in this area context for all interested people to build on.

Add a comment about this page