Introduction

These are summary notes from the heritage walk organised on 18th August 2018 as part of National Heritage Week. The walk followed a proposed mining heritage trail through the Glendasan and Glendalough valleys through to Glenmalure using existing walks, trails and forestry roads/tracks.

The walk was organised by Glenmalure Pure Mile Committee and included Glens of Lead representatives, interested group members and general public from Wicklow and surrounding counties. The walk was led by Charles O’Byrne.

These notes highlight information and some supplementary material given in talks given by Robbie Carter, Dave Shepherd, and Carmel O’Toole and have been prepared as an aide memoir for the walking group and can be read with their notes.

The walk commenced at the Wicklow Gap (Hero Mine Site) at 10am 18th August with 19 people in attendance including ex miner and special guest Robbie Carter who joined the group for the tour of the old Hero and 1950s mine sites in the Glendasan Valley. The Glendasan/Glendalough Valley walk was completed by 3pm and continued through to Glenmalure Valley where the walk was completed at approximately 6.30pm.

These notes were prepared by Dave Shepherd Secretary of the Glendalough Mining Heritage Project and Glens of Lead Committee.

Some of the detail in these notes, including diagrams, and maps have been taken from research and reporting carried out under the auspices of the Ireland Wales Programme 2007-2013 INTERREG 4A Metal Links, Glens of Lead and brochures produced by the Glendalough Mining Heritage Project and the Glenmalure Pure Mile Committee. Whilst these notes are written in the context of the walk they also form part of the communication strategy associated with the outputs from the InterReg Metal Links programme as well as furthering the interest in mining heritage in Wicklow and the work completed by the Glenmalure Pure Mile Committee over the last three years.

The interest in the walk and these notes will hopefully strengthen the formalisation of a Miners’ Heritage trail through the three valleys (the 3G’s).

Whilst documents and information are taken in the main from publically available documents, and from our own research, it would be appropriate to seek approvals and cite references if they are to be used in external papers or other similar forms of communications.

Historical Overview of Mining Activities in Wicklow (notes of presentation and discussions given by Robbie Carter and Dave Shepherd at the Hero Mine site, Wicklow Gap Road)

There is evidence of mining activity in the Wicklow Mountains since the Bronze Age including the copper mines in Avoca. This is supported by studies recently carried out under the Metal Links InterReg programme where a palaeoecoligical assessment of metal mining in Glendalough was carried out using peat core samples taken on Camaderry Mountain. Preliminary conclusions indicate possible mining from the eleventh century and rapid growth from the fifteenth century.

Up until 1960 Wicklow was the foremost mining county in Ireland with records supporting commercial mining in the area over the last 200 years in the valleys of Glendalough, Glendasan and slightly earlier in Glenmalure. The remains of some interesting buildings and mine workings survive from about six separate enterprises in Glenmalure as well as more concentrated sites in the Glendalough and Glendasan valleys.

There are further traces of lead bearing veins at Lough Dan, but in insufficient quantities to be exploited commercially. At Ballycorus, on the north east edge of the Dublin Mountains, the lead supplies also proved uneconomic to extract, but it was here that the smelter was built, by the Mining Company of Ireland, which turned the ore from Glendalough and other mine sites into exportable raw lead. Lead ore was also exported direct from Ireland to smelting facilities in other countries including the UK and Turkey.

The lead bearing veins in the granite consist of three principal minerals:

Galena: lead sulphide

Sphalerite: zinc sulphide (lesser amounts)

Pyrite: iron sulphide (minor amounts)

These are found within a vein accompanying non-economically useful quartz and calcite. The galena also includes traces of silver, which provided a useful by-line that added to the profits of the Mining Company of Ireland.

For the first half of the 19th Century lead mining in the Glendalough area was confined to the Glendasan Valley. It commenced around 1800, at the time of the construction of the Military Road and was developed by Captain Thomas Weaver a Welshman from the Avoca mines who was commissioned by the Government to look for gold but successfully found lead. In the years that followed he was in charge of the development of extraction and processing at the Glendasan site.

In 1825 the Mining Company of Ireland bought an “unnamed company’’ in a “confined and almost inaccessible lead showing in the wilds of Wicklow”. The mining works operated in Glendasan for the next twenty-five years in a profit/loss cycle that was not unusual for the mining industry.

In the early 1850s the extensive pattern of adits and shafts that had been driven below the Camaderry Mountain from Glendasan Valley broke through to the Glendalough Valley, close to the location of what is now known as the Miners’ Village and lead mining and processing operations then commenced at this location around this time.

Throughout the history of the lead mines in the area, the operations in Glendasan were far more extensive than those in the Glendalough (Glenealo) Valley, with the entire valley being scarred by mine workings from the Fox Rock Mine at the lower part of the valley to the West Luganure Adit, not far below Lough Nahanagan.

Lough Nahanagan was a glacial corrie dammed by a moraine and its role (prior to the construction of Turlough Hill pump storage hydroelectric station) was important for flows along the Glendasan River to mine workings at the Hero mine site as well as the small hydroelectric plant that later supplied water to the Wynne’s estate. In his talk, Robbie Carter mentioned the existence of a syphonic connection at the Lough that could be operated via a sluice gate to regulate flows to the 1950s mine workings at Moll Doyle and Foxrock. He remembers Mr Wynne giving instructions to open the sluice gate a few turns to control water flows in the river. He also remembers the end of the syphon pipe being left exposed when the Lough level was lowered as part of the operations of the power station.

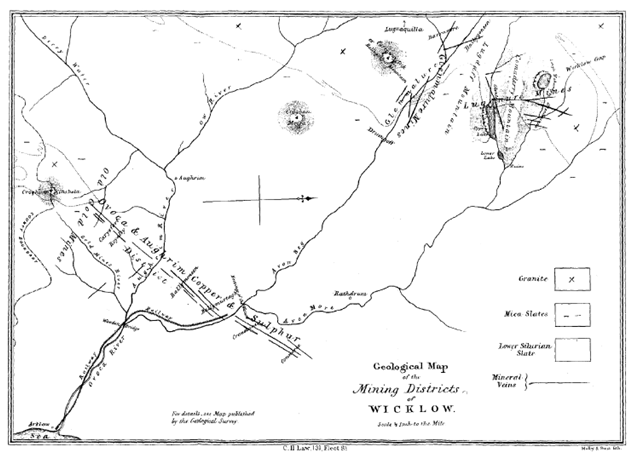

As mentioned during the walk, the 19th Century records of mining in Wicklow tend to refer to Luganure mines or Glendalough mines (Figures 1,2 &3). These terms cover operations in the Glendalough / Glenealo Valleys or the Glendasan Valley because works in these two valleys constituted a single operation run by the Mining Company of Ireland. It can, at times, be confusing as specific valleys are not always defined or clearly differentiated when reading historical documents.

The 1850s saw exploration in the Upper Glenealo Valley, which resulted in mining operations that came to be known as “Van Diemen’s Land” named after the Tasmanian penal colony. It was aptly named due to its extreme remoteness at the head of the valley close to the bridge crossing the Glenealo River at the top of the zig-zag trail that forms part of the Spinc loop walk.

From a viewing point on the Spinc trail towards the south facing side of the Glendalough valley, the upper adits and spoil heaps from mines can be seen. These sloped downwards from the Glendasan side towards the Glendalough valley to enable the ore to be transported out of the mine under gravity and aided natural drainage without resorting to mechanical pumps that were required in Van Diemen’s and Glendasan mine sites. In the latter sites water powered pumps or mule drives were necessary for dewatering mine workings.

The company enjoyed considerable profits through the 1860s and up to the end of the 1870s. Thereafter a fall in lead prices and increased investment in machinery and exploration meant decreased profitability. Lead was used in the roofs of public buildings, new houses built by nobility and gentry, glazed windows with lead glazing bars, water storage and piping and the ongoing usage in ammunition used by the British Army in their numerous armed conflicts in the 1800s.

The impact of the mining activity on the local population can be seen in the population figures for the townland of Glendalough for the fifty years between 1841 and 1891. Throughout the period the number of males exceeded the number of females.

1841 – 130: 1851 – 111: 1861 – 238: 1871 – 289: 1881 – 237: 1891 – 84

Mining continued into the 1880s in Glendasan, a little longer than in the Glendalough Valley, but due to falling profits the Mining Company of Ireland put the entire Luganure Mine up for sale in 1889. The Luganure mine sites were sold in 1891 and the Wynne family (who also owned mines in Glenmalure), are first mentioned as owners of the Fox Rock site at Glendasan between 1899 -1913. The Wynne’s continued to be principal owners and shareholders up until the final demise of operations.

Operations in the years following the MCI’s departure were small scale and sporadic, ceasing around 1900, but there was a brief renaissance, sponsored by the British government during the First World War that included further explorations at Fox Rock. This however ceased with the end of the war and it was not until the late 1940s when a survey of the Luganure mines centring on the Moll Doyle and Fox Rock lodes led to a final 10 years of mining activity in Glendasan, employing around 80 people under the auspices of the St Kevin’s Lead and Zinc Mine. In 1956 a Canadian consortium The Canadian Mining Company acquired rights to exploit the mines but this was short lived with the closure and abandonment of the mines in June 1957.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

During the tour of the Glendasan mine workings, an overview of the dressing floor, crusher house, water/power arrangements, and the crushed ore separation facilities was given by Dave Shepherd. The main buildings were described and the canal feature that supplied water from the upper reaches of the Glendasan River at a weir close to the bridge and old forge were explained. The group were told to look out for these features that are now adjacent to the reconfigured St Kevin’s Way.

The walk then followed the river downstream to the 1950s mine workings (following the St Kevin’s Way) where Robbie Carter gave an overview of work life in the Fox Rock and Moll Doyle mines and pointed out the location of various features including the compressed air and generator plant skids, processing plant, various spoil heaps and settling beds, mine entrances for Fox Rock and Moll Doyle mines, the magazine store where gelignite and detonators were stored, and the Mine Captain residence. Stories and accounts were given covering the:

- ‘commuting habits’ of mine workers arriving on foot, bicycles, motor bikes and in later years motor cars from as far away as Glenealy.

- tough winters in the valley; long lasting frosts that caused hands to freeze onto tools, and water in compressed air lines to freeze, ‘flame assisted’ techniques for thawing out frozen lines, and the arduous weather conditions that sometime delayed access to the site. Robbie mentioned that the position of the processing plant and the surrounding hills that left the area in shadow for much of the winter period.

- recovery procedures for miners who collapsed in the mine due to the effects of contaminated air. They would be lifted onto a bogey in the mine and brought outside into the fresh air and left until they revived with their work colleagues returning to work.

- indifference to health and safety. In those days personal protective equipment was unheard of. Indeed, any specialist clothing was kept in the office and reserved for visitors. Most miners went home in the clothes they worked in or decided to leave their wet clothes at the site in the hope they would dry out before they returned for their next shift. White dust and flushing water would have covered miners during drilling operations,

- wages of miners (shift and day workers) compared to council workers. The rates were marginally higher and bonus rates were available if ‘footage targets’ for excavations or production targets were exceeded. Underground workers were paid higher rates and this was seen as a progression for surface workers. It was typical for surface workers to make regular enquiries for any vacancies that may arise for underground work.

- bonus and piece work schemes in force at the time. A starter in the mine would work on the surface and earn a wage of 1/- per hour for a 48hr week with experienced workers managing the processing plant and auxiliaries earning up to £5 per week. Underground workers would earn up to £8 per week.

- working arrangements. For Robbie the mine worked 24/7 shifts with three shifts per day of 8 hrs per shift with typically a 20-minute break during the day. He related stories from the Canadian management who could not understand miners taking a day off work to pay their respects in the event of a death. This came to the fore during the death of James Mernagh

- quality control schemes and the penalties for poor sorting of ore

- practical jokes played on young recruits when carbide lights blew out after a planned explosion

- manning arrangements inside and outside the mine

- areas where spent carbide was emptied

- re-entry of the Moll Doyle mine in recent years where abandoned wheel barrows and tools from the 1950s were re discovered

As mentioned above, the end of lead mining in County Wicklow came in 1957 at the Glendasan site; the quantities of ore available could not be economically extracted.

As Robbie Carter related, the end was also precipitated by a fatal accident on 22nd January 1957, in which a young father, James Mernagh, (24 year of age) was killed. The group walked over to the memorial to James Merhagh next to the Fox Rock mine entrance and paid their respects and Robbie Carter (20 years of age at the time) took time to sensitively relate the incident in which he was seriously injured working alongside James. Carmel O’Toole read a short poem relating the life experience of the miners working in the Fox Rock and Moll Doyle mines at the time.

The definitive cause of the accident could not be proven but considered to be their drilling rig inadvertently entering an unseen pre-existing explosive charge hole drilled in a previous blasting operation. The drilling operation set off a detonator and the ensuing gelignite explosion blew back onto the two miners. Robbie gave the group a valuable insight into the incident, the impact on families, the prolonged process for compensation (4 years), his long recovery and the lifelong injuries he sustained and carries to this day. Robbie made special mention of the doctor and medical staff at Loughlintown Hospital who cared for him and helped in his recovery from the serious blast injuries to his face, arms and legs.

Robbie mentioned the work carried out on the Fox Rock mine that required a 7’x4’ mine to be driven into the hills for half a mile and the ensuing plan to develop the mine back towards Camaderry as part of an exploratory search for more economic lead veins. The latter was not fruitful.

In the area of the Fox Rock and Moll Doyle, Robbie gave an overview of the site explaining the location of the various buildings used in the 1950 operations. On the south side of the river were corrugated Nissen huts housing diesel generator and auxiliary plant used to support the mine operation on the north side of the river and the concrete magazine store. Evidence of the piers that supported the original wooden railed bridge (now demolished) at the west of the site were clearly evident. This would have been the main link linking the Moll Doyle mine and neighbouring auxiliary plant to the processing plant on the north side. The current concrete bridge was a later addition.

The processing plant consisted of concrete hopper that received tipped ore from the mines that then served electrically driven crushers, rollers, jigging and centrifugal separators. The end product of concentrated ore was placed into 1cwt bags and sent to Wicklow for export to the UK and Turkey for smelting. The typical price was £100 per ton with output between 60-70 tons per week.

The building structure, now demolished, had an unusual history being salvaged from a wooden structure used during a state event in the 1950s and relocated to the site. The remains of the supporting wall are still visible on the south side of the plant.

During the tour, Robbie drew attention to various remaining pieces of plant including parts of the vacuum centrifuge hoppers, crusher wheel and drive shaft and rotating screen assembly. He mentioned that when the mine operation finished the site contents were auctioned and sold leaving very little behind except those parts too heavy to move or which had little residual value. The auction took place over a period of 3 days with great interest from local businesses. Most items were sold for their scrap value.

Robbie mentioned that fines from the process caused some sedimentation in the river that required periodic ‘ploughing’ to remove some of the material so that it did not interfere with the down stream weir to Wynne’s hydroelectric plant.

The walk then continued down the miner’s road (now part of St Kevin’s Way) towards Glendalough passing the site of Hayes farm (the remains of the old walls and garden are still visible, including a Monkey tree near the magazine store) down to the remains of Fiddlers Row where the footings of old homesteads can be seen amongst the Coillte forest. Carmel O’Toole read a poem about the Row that included the names of all the residence purported all single men at the time.

The remains of the old two storey house were examined. It is believed to be part of the small housing settlement that formed part of Fiddlers’ Row and could have housed the mine captain.

On the north side of the valley the remains of lazy beds and walls could be scene. This would have also been part of a mining settlement taking advantage of their south facing direction.

Dave Shepherd and Robbie Carter gave a short account given of the downstream weir that supplied water to the old hydro station owned by Wynne’s. The area close to the weir is believed to be the location of a ford or bridge that was once the original St Kevin’s pilgrimage river crossing prior to the construction of the current miners’ road that goes through to the Hero mine site.

At this point the group bade farewell to Robbie Carter and recognised his presence in providing a personal and invaluable link to the history of mining in Wicklow.

The group then left the Glendasan Valley walking over the shoulder of Camaderry Mountain down to the Glendalough Upper Lake (Bolgers Cottage Educational Centre).

Geology and Geomorphology (Notes from presentation and discussion by Dave Shepherd at the Hero site on the Wicklow Gap Road)

The geology of the lead-bearing rocks of Glendalough and Glendasan (Figure 4) is the result of the movements that occurred in the Earth’s crust between 535 and 400million years ago, an event known as the Caledonian Orogeny. This involved tectonic plates moving apart to form a wide stretch of ocean, the Iapetus Sea. At this time the rocks now forming NW and SE Ireland were on different continents on opposite sides of this sea, with Wicklow lying on the southern side. Muds and sand that collected on the bed of this sea were compressed by their own weight to form sandstones and mudstones and eventually slates. As the continental plates came back together and overrode each other the sea was closed and led to the deformation, compression and cleavage of rocks and to the intrusion of molten granite from positions deep below the earth’s outer crust. The heat from the granite caused the metamorphosis of the adjacent slate to form the schists of the Eastern part of the Glendalough Valley.

The Leinster granite, of which Wicklow forms a part, is the largest granite body in Western Europe, and dates from about 405 million years ago when it cooled and crystallised at a depth of between 5 and 10km below the Earth’s surface at a location south of the Equator, at about 30°S. As the granite cooled the veins of minerals, including lead, were formed by metal rich deposits from the seabed being drawn by convection into fractures in the granite at the point where it met with the contrasting rocks.

In Wicklow, all the lead bearing veins are found close to the junction of the granite and schist, as shown in the geological map included in these notes for information.

In the Glendalough Valley evidence of the underlying geology can be seen through the contrasting vegetation which is reflected in the different soils that developed during the above evolution. This is apparent at the junction between the underlying Granite, to the west and schist to the east on the north side of the valley just to the east of the Miners’ Village.

The granite was first exposed on the surface of the earth around 350million years ago, but was subsequently overlaid with depositions of sandstone, below another sea. There was a further uplift of the Wicklow Mountains and so it once more exposed and then eroded to form the current rounded uplands. This occurred between 36 and 10 million years ago, but at this time the lead bearing minerals would have been concealed inaccessibly deep below the earth’s surface.

It was only the most recent Ice Age that commenced around 1.6million years ago, that eroded the landscape and formed the steep-sided U-shaped valleys of Glendasan, Glendalough and Glenmalure that exposed the lead veins and offering relatively easy access into the Earth for extraction. This period of glaciation ended around 10,000 years ago and the landscape of the all the 3G Valleys presents clear examples of glacial formations, with near vertical sides and exposed rocky crags, scree, ribbon lakes, contained by glacial moraines, high corries and waterfalls. It is understandable why the 3G Valleys are noted for their geological and geomorphological interest.

The powerful sculpting effects of the glaciers ceased when the ice retreated, but the landscape continues to be modified, by natural forces, on a daily basis. Freeze thaw actions on the exposed rocks cause sections to break off and fall into the valley; smaller elements form the natural scree slopes, larger sections fall in the form of the boulders that are such a characteristic feature of the valley.

Eventually, in a maybe another million years or two, these actions will fill in the valley. It is possible to observe these actions at work on the edge of the Miners’ road up to Van Diemen’s Land, where the drainage channels to the side of the track are slowly narrowing as the weight of the boulder fields push the soil and scree of the hillsides downwards.

The action of water is also clearly evident in the landscape especially from the dramatic events of the floods as recent as January 2010. In all the valleys it is clear to see how rivers have changed their courses through erosion and deposition that are clearly observed with reference to earlier maps.

Figure 4

Historical Overview of Mining Activities in the Glendalough Valley (notes of presentation and discussions given by Dave Shepherd on the Miners’ Road, Miners’ Village, Van Diemen’s Land and from the Spinc)

The walk then continued toward the Miners’ Village where details were given by Dave Shepherd at the ‘Miners’ Village’ and on the zig zag path up towards Van Diemen’s Land mine site.

It was pointed out that the term Village is a misnomer and in reality the mine site would not have had a significant population except for farmers, caretaking staff or a temporary bunkhouse. Most of the workers would have commuted to the site.

The site at the Miners’ Village in Glendalough was only a viable mining and processing operation for around a quarter of a century. It worked in parallel with the Glendasan mine commencing operations from the mid-1850s. The site was developed following the discovery of ore on the northern side of the valley with resulting connection with adits following the seams of ore below the Camaderry Mountain from Glendasan. The site worked at full capacity only until the late 1870s from when operations were reduced.

The mines were working at a profit for only seventeen of these years from 1853- 1870. Large investments were made in equipment around 1870, most notably the funicular link between the Miners’ Village and Van Diemen’s Land, but these investments were never rewarded by the extraction of enough ore to counteract the effect of a very low price for ore at this time.

The Miners’ Village site was principally a processing plant, with the mouths of only three adits and two shafts opening into the valley, (compared with multiple adits and shafts in Glendasan). However, considerable quantities of ore were handled; a large proportion of the ore extracted from below the Camaderry Mountain travelling down the sloping adits to the levels in Glendalough as well as processing ore from the adits in Van Diemen’s Land.

The physical remains visible today are only a very selective reflection of the activities and former installations at the site. Weathering processes, movement of spoil, and interference of the site created by routing of paths, waterways, abandonment, equipment relocation, and demolition have meant that what survives is only partially representative of the site in its working years as depicted in Figure 5. Significant work was carried out under the Metal Links project to develop an interpretation of the sites and the Glens of Lead information boards at the Glendalough and Van Diemen Land sites have artistic impressions of what the sites would have looked like up to 1880s.

As found during the walk, an uninformed eye is unlikely to interpret mine workings and remains. A good example is picking out the remains of the dam structure and the funicular route up to Van Diemen’s Land.

The site would have been a hive of activity and concentration of machinery and timber structures. There is still room for considerable research and archaeological investigation at the site in order to come to a more complete understanding of the operation of the site. This is ongoing and carried on by bodies such as the Glens of Lead, the Wicklow Heritage Forum and the Mining Heritage Trust of Ireland and informed specialists in Mining Heritage, Industrial Archaeology, Local, Social and Economic History as used during the recent Metal Links project.

The extraction of lead ore from the mines involved a sequence of specific processes: forming the tunnels (adits and shafts); extracting the ore and waste material from the tunnels; transporting the ore from the mouth of the adit to the processing areas; sorting the ore, crushing the ore, washing and settling the ore to extract the useful material; disposing of the waste rock; transporting the ore for conversion into lead elsewhere, in this case at Ballycorus.

The site would have been laid out by specialist engineers on behalf of the MCI by managers and engineers drawing on previous experience, possibly in the tin and copper mines of Cornwall. (The village was known for many years as “The Cornish Village” reflecting the influx of specialists from there at an early period.)

Efficiency and profitability would have been paramount with minimal consideration given to the comfort of personnel, and no conscious consideration of any aesthetic aspect, but optimum use would have been made of the natural topography using gravity to assist in the transportation of heavy materials. This point was well made during the tour and discussions where credit was given to the innovation of the mining engineers in their construction of the tramways and inclines towards Glendalough in the adits from the Glendasan mine workings.

The underground workers formed teams, of between three and twelve men, known as “pairs” and were paid on commission on the basis of the useable ore extracted. This would be consistent with the 1950s accounts given by Robbie Carter. The most respected and those who commanded the highest proportion of the proceeds were the “Tributers” who actually mined the ore inside the mountain. They were supported by “Tutworkers”, responsible for cutting the shafts and adits into the mountain. The teams were paid on the basis of commission, so the administrators who checked and recorded the quantity and quality of the ore extracted by each team would have had a key role.

Those who worked in the processing areas outside of the mountain, were known as surface workers, and would normally have included women and children as well as men. They would have worked mainly in the dressing floors. The question was raised during the tour on the employment of child labour. It is a high probability however, a parliamentary Inquiry into child labour of 1841 reported no children employed in either Avoca or Glendalough. 19th Century tourist accounts report local women and children were more likely to be employed in the burgeoning tourist industry.

There are three “levels”, which are the exits from the horizontal adits in the side of the valley above the Miners’ Village. They would however be the subject of continuous improvement and change to suit mining operations, spoil deposition and whilst the adits are marked on the 1910 OS Map the same map shows a fourth level, but the same does not appear on the survey section of 1948. There would also be the confusion on what constituted an adit, draining point, or spoil platform.

There are also two shafts marked on the steep slopes above the site. The lowest of the levels is accessible via a short climb from the hopper location or by the zig zag trail from the Miners’ Road that starts close to the Amy Healy memorial. It is thought that this adit may have been principally used for draining the mines of water rather than a main exit for material extracted from the mine.

The two other levels are further up the side of the valley, and gravity was the principal force used to carry the ore bearing rock from the exit to the adit to the processing areas at the Miners’ Village.

The location of these levels were seen on the side of the valley from the vantage point on the Spinc as the walk passed Van Diemen’s Land and looked down and across at the north face of the valley. The levels were indicated by the white fan of soil descending from almost graphically horizontal lines. These are the lines of former barrow ways where workers would have wheeled the soil away from the levels, disposing of the waste material down the mountainside. Remains of the posts that supported these barrow ways can still be seen.

The valuable ore bearing rock was sent down to the sorting floor area below, by some form of rail system or funicular tramway. There are remains of the track rails, wire chains and posts that lead down the valley side. Such a system would have required careful control and braking systems to allow upward and downward travel of full and empty wheeled bins. The incline is close to 45 degrees and there are reports of ‘wagons rattling at fearful speed’. There is a similar incline on the tramline installed to Van Diemen’s Land where there is a definitive scar to the south of the Glenealo waterfall.

Ore bearing rock from the north side of the site would have been stored in the Hopper that has an inclined cobbled floor in which the material would have been carried away in barrows to be sorted on the nearby cobbled dressing floors.

Water was central to the entire operation, and without the Glenealo River operations at the site would not have been viable. Surviving evidence of this is the large dam to the west and uphill of the Village. Water from this reservoir ran in high level timber channels known as “leats”, and turned a water wheel which in turn powered the crushing machinery, for which high specific loads were required to break the rock. Water was also essential to the processes carried out after the crushing of the rock, when agitation and settling were used to separate the useful metallic ore from the waste residue.

All rivers naturally move their course over time; but in the case of the Glenealo River the 19th Century miners were entirely reliant on the river to power their operations and they obviated risks by creating a Dam and diverting water into this reservoir which eventually returned to the river after use in turning over shot water wheel powering the crusher (Figure 5). As discussed during the walk, they may have also diverted, enlarged, or created a branch of the river to supply water to the processing area. From Figure 5 and inspection of the area it is estimated that the water flow to the 5m diameter water wheel could have been around 1m3/s and this would have been sufficient for day operations of the crusher generating a shaft power of around 30kW for the stamping mill.

In all these processes there were vast quantities of waste generated mostly consisting of quartzite, the mineral that contains the veins of lead. This would have been disposed of as conveniently as possible, moving it far enough from the processing areas not to cause obstruction but with the minimal use of labour and material; hence the extensive spoil heaps that encircle the site and scar the mountain sides. As pointed out during the walk there is a lack of vegetation on these heaps due to residual minerals left within the spoil.

The final operation was to transport the ore away from the site to Ballycorus (or export) where it would be smelted into lead. Typical loads per month at the peak would have been around 120 tons. Pack mules and horses would have been used, and possibly carts too, as the Miners’ Road was of a sufficient load bearing capacity. Animals may also have been used to power some processing machinery, and would have been the only transport for machinery and ore to and from Van Diemen’s Land prior to the construction of the funicular. The large enclosure in the collection of buildings shown during the walk would have provided secure space for these animals.

As discussed, the Miners’ Village was an industrial processing plant, rather than a village. As mentioned above it is inaccurate to refer to the collection of buildings as a settlement. Most of the workers would have walked to the site from their homes in Glendalough or Laragh. These would not have been considered exceptional journeys at the time, although the additional climb and distance to Van Diemen’s Land easily explains its name.

There were several adits at Van Diemen’s Land accessed by a miners’ path the remains of which are visible around the line of the tramway route to the south of the Glenealo water fall. The biggest challenge for the Van Diemen’s mine workings was water ingress and the need for continuous dewatering. To this end an over shot water wheel (large diameter circa 10m) driven by head water extracted from the upper reaches of the Glenealo river was used to drive pump(s) via connecting flat bars (rods) to displacement pumps in the mine workings. Back-up power was obtained from a mule/horse whim close to the mine working. The Glens of Lead information board illustrates the arrangement used for the Ennis shaft at around 1870.

There would have been a certain amount of initial sorting at the site, as evidenced by a hopper and dressing floor before the ore was sent down to the processing plant in the valley bottom. Mine buildings in Van Diemen’s Land were limited and included the agent’s house, and structures associated with the dewatering plant, hopper and dressing floor and tramway.

It would be usual for working families to combine working for the MCI with reliance on their own home grown food, even where there was an income being earned through mining. Some miners could have travelled longer distances and they may have stayed at the Glendalough site, during the week, or in hostels type accommodation in the nearby settlements.

It is believed some of the buildings at the site were certainly used for such accommodation, but would probably have been bunkhouses rather than family homes. The row of eight cottages near the head of the upper lake can be identified as being constructed by the company, as they differ in design and layout from the indigenous vernacular of the Wicklow Mountains. There is evidence of lazy beds on the opposite side of the valley, however this does not indicate that the houses would have been inhabited by families; bachelors and men working away from their families could have supplemented their diet by what they could grow in the vicinity. As mentioned on the walk, a mill stone has also been found in the locality of the Upper Lake but further research is required to establish its original function and likely location in the area.

Mining operations were became increasingly limited from the early 1880s onwards and there are records of sheep being brought in to graze on MCI lands in 1883-84 in an attempt to make some money out of the land. The lease on the surface land belonging to the MCI was sold in 1889 for “forestry, sheep and rabbits”.

Reworking of existing waste tips continued for a few years after mining ceased but by 1900 all production of ore had stopped.

It is likely that with the end of mining at the site, any items of value would have been taken away, though there may have been some delay while there were still hopes of restarting the mines. The land was not good enough to support significant agriculture and this, combined with the remote location, made the buildings uninviting for alternative use. Portable goods such as roof slates and timbers may have been carried away for use elsewhere, speeding up the process of decay at the buildings.

The last house to be built in the ‘Village’ retains some internal plaster and may have kept its roof, and been in sporadic use for a little longer. More research is required for the years between the 1880s and the First World War when in 1913 new machinery was imported into the site to crush and extract further ore from the existing spoil at the site. As far as can be established, water was still required for washing and separation functions and possible machinery drives with water carried in high level leats from the dam. The rusting geared crusher can still be seen amongst the spoil heaps to the east of the Village and the current form of the main spoil heaps date from this time.

A reality is that near to the Hopper building, the soil would have been dumped on top of earlier dressing floors. Photographic evidence from the 1920s shows a large timber shed, which would have enclosed machinery. As mentioned by Robbie Carter this building was destroyed in a severe storm in 1935 resulting in the site being abandoned thus ending the industrial age in the Glendalough valley. Photographs from the time show a large building clad with corrugated iron with an elevated leat supplying water into the processing plant.

Figure 5

Heritage Walk into the Glenmalure Valley (notes of talks given by Carmel O’Toole, Charles O’Byrne and Dave Shepherd)

The walk continued along the Spinc breaking off to the north towards Prezen Rock and then connecting with the Wicklow Way walk towards the Glenmalure valley at the saddle between Prezen Rock and Mullacor.

The route followed the Wicklow Way on forestry roads up to a junction with an old track that connected the Glenmalure valley to the Wicklow Way formed from an old mule trail used to bring peat to the Ballinafunshoge smelting plant.

Our walk followed the old mule trail down to the site of the old smelting plant and was a zig zag trail lined in part by dry stone walls acting as retaining walls on the Mullacor side of the route and through a Scots pine and Coillte forest. On the route down was a collapsed structure that would have originally formed part of a vertical ventilation shaft to underlying mine workings of the Ballinafunshoge mine. The route, joined in part with forestry tracks, then exited at the valley floor into the area once occupied by the Ballinafunshoge Smelting House alongside the Mill Brook water fall. The area has now been developed as a Coillte recreation park and many of the original building foundations and remains were removed about 10 years ago. The layout of the area is shown in Figure 6.

Carmel O’Toole took time to point out the features of the site on either side of the Glen Road for which remnants of the original smelting house and processing plant were in evidence and would have served the mine sites around 500m SE from the area.

The area is well described in the 2016 Pure Mile brochures and Carmel O’Toole gave a detailed account of the site’s history and the demarcation lines up the valley marked by the Avonbeg river and the ownerships of land north and south of the river. The early mines probably started in the late 1700s and would have operated around the time of the 1798 rebellion and continued to operate in a ‘boom and bust’ cycle through to the end of the 19th Century. Examination of spoil heaps suggest that the early mining efforts were poorly managed by land owners and farmers and they were described by later mine developers as inefficient operations wasting much of the ore removed from mines. Output levels varied and at the height of production up to 400 tons of lead per annum was produced with recorded prices for lead in 1811 reaching £30 per ton.

Many of the mines extended at different levels into the hillside for distances up to 900m with the primary metal mined being lead although some silver, zinc and copper was found in the Baravore mining area. Most of the mine adits have been blocked off but some water leakage from one of the main mines is still present with leached deposits colouring the water in road drains.

Carmel explained features on the south side of the valley developed by Parnell in what could have been described as exploratory or speculative moves into the mining industry that were not pursued for economic reasons.

The old smelting house was fired using peat brought by mules from peat cuttings on Mullacor hillside. The furnace and chimney would have been a prominent feature in the house structure and survived for a period of time but is now no longer visible.

The life of the smelter was however short lived and research revealed that the building was later converted into a miners’ office and a residential area for mining families. From reports in the mid-19th Century approximately 30 men worked in the mines and it can be assumed that some of them would have had families accompanying them. The presence of a School House nearby would support the existence of miners’ families.

Of note was that various names given to the bank areas upstream and downstream of the Avonbeg River that existed beyond the life of the mines and used to differentiate the various parts of the area. For example, the Flooring Bank brings you uphill to the Mill Bank under which the Mill Brook flows and the downhill side of Baravore was known as ‘The Smelting House Bank’.

As with the Glendalough Valley there are mature Scots Pine trees nearby planted originally to support the nearby mines for pit props, building floors and joists and leat trestles.

Whilst at the Smelting House, Carmel related the story of the well documented tragedy that occurred on 23rd March 1867 when a heavy snow followed by a fast thaw and heavy rain resulted in a land slide at the Smelting House site washing away a miners’ cottage with the loss of two children’s lives and injury to another. Reports at the time likened the Mill Brook water fall to that of Powers Court in full flow. Photographs were shown on how the area looked before the area was damaged by the land slide and by later demolition of the building outer wall and chimney breast. In later the years in the 1940s the Wicklow County Council built a ‘swim bath’ for use by local farmers to dip their sheep.

Over the road are the remains of the old mine crushing and grinding plant and wheel pit that are heavily over grown. The plant was powered by a water wheel supplied by water carried in overhead leats from the upstream sections of the river to derive the necessary head to turn the water wheel and connected crushers and grinding plant.

Figure 6

During this walk the opportunity was not taken to visit the nearby mines on foot except to provide the group with a reminder to examine them on the way back along the Glen Road after inspection of the Baravore site.

The group left the Ballinafunshoge recreation site and walked NW down the Glen Road to the Car Park at the Knob memorial over the ford toward the Con Hopkin’s old forge and into the Baravore townland where the recently rehabilitated New Crusher House was accessed via the Miners’ Track.

Dave Shepherd gave a brief over view of how the crusher house would have operated taking its power from the large diameter water wheel fed from the nearby moraine dam/reservoir and this then driving the crusher plant. The entry points in the masonry walls for various floor joists for the different floors could be seen together with the ore entry points at the upper level and the side entry point for the main driving shaft and bearing support for the main drive shaft from the water wheel. The eastern wall above the water wheel bearing had an arched architectural feature set in the wall that could have been a strengthening feature or part of an earlier access or window. It is believed the New Crusher House was over capitalised and did not see too much service and could have been an attempt by the mine owner Henry Hodgson to impress possible investors into his mining ventures at Balavore and his other mines at Ballinafunshoge.

Carmel O’Toole explained that the House was the best extant example of a rolls crusher house in Ireland and gave an overview of the challenge to preserve the structure that had been protected in part for years by the Coillte forest. When the trees were removed, the building deteriorated quickly and had to be carefully conserved in a jointly funded programme between Coillte and the National Heritage Council. The funding also included the development of the Heritage loop trail that takes in both the New Crusher House and links this site to old adits on the hillside and nearby mining buildings. The site was nominated for the ‘Adopt a Monument Scheme’ in 2016 and the description of the site is well documented in the Cullentragh Park Bolenaskea Baravore Pure Mile Glenmalure 2017 brochure.

The visit into the New Crusher House ended the 2018 Heritage walk and whilst this could be a natural end to the proposed Mining Heritage Trail the same could be extended a short distance to include the Heritage Looped Trail up to the Hostel and back down the road towards the footbridge and ford. This extension would take in the old crusher house that dates back to the mid-19th Century, Harney’s Cottage, and the Miners’ Cottages that line the road upstream from the Glens of Lead pictorial interpretation panel of the area.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page