29. The Resurrection of Dr. Emes

Sir Richard Bulkeley, the Second Baronet Dunlavin, was the man responsible for developing the village on its present site (his father, the first baronet had actually founded the settlement c.1660). In his later life, the second baronet became interested in a religious cult called the French Prophets, who operated in London, near where he lived (Surrey). He was a prolific writer, and his pamphlets engendered many replies; the title page of one is shown in today’s illustration – this is one of the oldest books in my collection. Bulkeley also became exceedingly eccentric (to the extent that his will was contested on the grounds that he was ‘non compos mentis’). Anyhow, Sir Richard once supported an attempt to bring a medical doctor back from the dead. Enjoy the read…

The resurrection of Dr. Emes

In his later life Sir Richard Bulkeley, long suffering physically, also seemed to be becoming more mentally unstable, and became an ardent follower of a movement known as the French Prophets.[1] Bulkeley was attracted by the ‘New Jerusalem’ ethos of evangelism and reform and hoped for a comprehensive universal church.[2] Dunlavin was the proposed location for Bulkeley’s personal ‘New Jerusalem’ and was intended to become a centre of proselytism and evangelical learning. A chimneypiece in Bulkeley’s residence at Old Bawn, Tallaght, depicted the scene of the rebuilding of Jerusalem from the Book of Nehemiah [also known as the Second Book of Ezra].[3] This was indicative of Bulkeley’s psyche and his plans for the village of Dunlavin were characteristic of his thinking. Regarding his health, Bulkeley claimed that he had actually been cured of ‘continuous headache, of stone and of rapture’ [sic: rupture?], so that he was no longer required to wear a truss.[4] However, in reality Bulkeley showed all the signs of a severe and degenerative spinal disease.

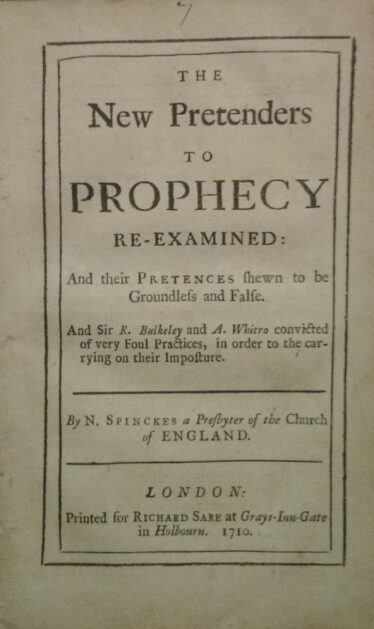

This situation did not escape the notice of one female prophet, Anne Topham, who promised Bulkeley a cure. Her ministrations did little good but, in the process, she extracted large sums of money from her patient. The French Prophets later expelled Topham, but the experience did not shake Bulkeley’s belief in the movement.[5] In defence of the prophets, Bulkeley wrote ‘An answer to several treatises, lately published on the subject of the prophets’, in which he defended the prophets by ascribing a long list of cures to them and by pointing out that the genuine nature of their speaking in tongues when under inspiration.[6] This tract prompted a flurry of replies,[7] including one published in London in 1710 by N. Spinckes entitled ‘The new pretenders to prophesy re-examined and their pretences shewn to be groundless and false. And Sir Richard Bulkeley and Abraham Whitro convicted of very foul practices in order to the carrying on of their imposture’ (see illustration). The excitement inspired by Bulkeley’s writings was hardly surprising, as he had a proven track record in the field of ecclesiastical debate, always ready publicly to defend religious teachings in which he believed.

By now Bulkeley had latched onto another prophet, Abraham Whitro[w], who had come to prominence by promising Doctor Emes, a medical practitioner on his death bed, that he would experience a speedy resurrection, and announced that the event would happen on 25 May 1708, five months after the physician’s interment.[8] On the appointed day a multitude of believers assembled at Bunhill Fields cemetery between 12 noon and 6 p.m. (the hours named for the expected miracle). The prophets expected that they would be ‘guarded by an angelic host, that the dead man would rise without any disturbance from his grave and that he should walk naked, but without shame or indecency to his own habitation’.[9] Unfortunately for Whitro[w] and his followers, Emes failed to rise to the occasion!

Decline of the prophets

Following the Emes debacle, the prophets went into decline.[10] Bulkeley, however, remained loyal to Whitro and refused ‘the test of sense’ as conclusive in a matter so highly spiritual as the resurrection of Emes. He penned a controversial introduction for a work published by Whitro in 1709, in which he questioned those who did not believe that Emes rose from the dead.[11] Meanwhile, Whitro and his wife Deborah were ostracised by the prophets and accused of ‘speaking their own words in the person of God’, which caused a schism that further divided the depleted movement. Whitro was accused of being ‘always drunk and beat[ing] his wife so grievously since he was inspired that she was in danger of her life’.[12] In his preaching though, Whitro used the image of Christ the carpenter building the New Jerusalem in the fashion of the biblical Nehemiahan account. The builders of Nehemiah’s New Jerusalem were soldiers and operated with both the trowel and the sword. This had resonances with Bulkeley’s personal vision of building a utopian settlement in Dunlavin,[13] though, by this time, his health was failing badly. Sir Richard Bulkeley died on 7 April 1710 and he was interred in Ewell in Surrey. As he died without male issue, the baronetcy of Dunlavin ceased with him.[14] Bulkeley’s writings on many subjects form part of his legacy, but he also left a more tangible legacy in west Wicklow – Dunlavin village, which was inherited by his niece Hester, who had married into the Tynte family. So began the Tynte family’s long association with the west Wicklow village of Dunlavin.

ENDNOTES

[1] The most complete history of Dublin on the web – Parish of Tallaght’, http://indigo.ie/~kfinlay/ball1-6/Ball3/ball3.1.htm (visited on 4/7/2001).

[2] Hillel Schwartz, The French Prophets: the history of a Millenarian group in eighteenth century England, (Los Angeles, 1980), p. 72.

[3] Schwartz, The French Prophets, p. 273.

[4] Edmund Calamy, An historical account of my own life, with some reflections on the times I have lived in, ii (London, 1829), p. 75.

[5] Kevin Breathnach, ‘Dunlavin’s University College’, Dunlavin Festival of Arts brochure, xxii, (2004), p. 44.

[6] Richard Bulkeley, An answer to several treatises, lately published on the subject of the prophets (London, 1708), pp 40-90 passim for lists of cures. On pp 92-4 Bulkeley averred that ‘Mr. Lacy, who had not read a Latin book for twenty years last past, when under the Latin impression, spake that language fluently, without being able to construe his speeches’ He also cited the case of ‘Mr. Dutton, a young gentleman, an attorney in the Middle Temple, who has no more Latin than is just necessary for his profession, but knows not one Hebrew letter from another, nor hardly a Greek one, would utter with great readiness and freedom complete discourses in Hebrew for near a quarter of an hour together, and sometimes much longer’. Bulkeley confessed that he could ‘not talk Hebrew, but I catched at several words here and there which I knew to be Hebrew – of all which he understood not one, but had an impression upon his mind that it was a hymn of praise to God for the calling of Israel. And afterwards, under inspiration it was declared to him in my hearing “thou shalt speak the Hebrew language better than any does speak it”.’ Dutton was evidently more coherent than some other prophets. For example, one, Durand Fage, uttered the phrase ‘Tring trang, swing swang, hing, hang’ while inspired. The words were recorded by a bemused Nicholas Facio, who did not recognise them despite being conversant in many languages! Edward Smedley, History of the reformed religion in France, iii (London, 1834), p. 309.

[7] Bulkeley’s tract caused quite a stir. Some of the replies it inspired follow: Anonymous, Reflections on Sir Richard Bulkeley’s answer to several treatises, lately publish’d, on the subject of the prophets (London, 1708). Edmund Calamy, Sir Richard Bulkeley’s remarks on the caveat against new prophets consider’d, in a letter to a friend (London, 1708). Anonymous, The Prophets; an heroick poem. In three cantos. Humbly inscrib’d to the illumin’d assembley at Barbican [and occasioned by Sir R. Bulkeley’s ‘Answer to several treatises, lately publish’d, on the subject of the prophets’ of the reign of Queen Anne] (London, 1708). Benjamin Hoadly, A brief vindication of the antient prophets from the imputations and misrepresentations of such as adhere to our present pretenders to inspiration (London, 1709). N. Spinckes, The new pretenders to prophesy re-examined and their pretences shewn to be groundless and false. And Sir Richard Bulkeley and Abraham Whitro convicted of very foul practices in order to the carrying on of their imposture (London, 1710).

[8] Schwartz, The French Prophets, pp 273-6 passim.

[9] Spinckes, The new pretenders to prophesy re-examined, p. 49.

[10] Smedley, History of the reformed religion, p. 313.

[11] Abraham Whitro, The warnings of the eternal spirit with a preface by R. Bulkeley, (London, 1709), B.L., 875.b.18. In his preface Bulkeley wrote ‘If I should ask these men how they knew that Mr. Emes was not raised at the time predicted, they must not own it to be a sufficient answer (even if they had been then in the burying place) that they did not see him; for I have shewn out of scriptures that the eyes of unbelievers are holden, they are too dim to perceive a raised body’, p. 19.

[12] Dr. Woodward, a clergyman engaged in controversy with the prophets, cited in Smedley, History of the reformed religion, p. 313.

[13] Schwartz, The French Prophets, pp 276-7.

[14] Lord Walter Fitzgerald, ‘Dunlavin, Tornant and Tober, County Wicklow’, Journal of the Co. Kildare Archaeological Society, viii, 4 (1913), p. 221.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page