Dublin Gaelic Merchants and Traders with Wicklow Roots

The Gaelic Irish in the 1600s

The period between 1600 and 1700 was the most disruptive phase for native landowners in present-day County Wicklow. In 1600, the Gaelic Irish held on to their traditional territories, maintained their tribal structures, spoke their own language and behaved according to their own laws. By 1700 everything had changed; they had lost most of their lands.

But, not all Gaels were forced to leave their homes. Only a quarter of the native population were landowners. They belonged to the ruling elites or held specialist roles in the learned professions. Some who lost their land were demoted to tenant farmers. Alternatively, if evicted, they existed as rural middle-men trading agricultural produce. Others became teachers, scholars, clerics, smugglers or rapparees. It is becoming increasingly clear that an important number spent time beyond Ireland’s shores where some families involved themselves in business and trade or joined the armies of Spain and France.

Trade offered opportunities for Catholics

For those who stayed in Ireland or returned home after a period overseas and held onto their Catholic faith, trade was the only road to wealth that was not blocked up against them by law. This is because the new Protestant landowners and colonisers held trade in contempt and reluctantly acquiesced to Catholics becoming involved in related pursuits after the Restoration of Charles II in 1660. As a result, the authorities did not prevent the development of native links to rapidly-growing commercial activities in the towns and cities of Ireland. It was in their interest to ensure that daily commerce and the wealth of the country continued to improve.

Gaelic Wicklow Traders: Migration to Dublin

Indigenous involvement in commerce had deep historic roots. For example, Emmett O’Byrne—writing in History Ireland May/June 2005—indicates that: Trade was … common between the Wicklow élites and the English, particularly in wine, timber, butter, weapons and corn. The depth of this commerce was captured in Gerald O’Byrne’s 1392 offer of a barge to Esmond Berle, a Dublin merchant, as payment for debts. In 1395 Phelim O’Toole also attested to trade’s importance, exclaiming ‘for without buying and selling I can in no way live’… Gaelic families, like these, who had long experience of commerce would have been a vital catalytic force in the process of modern urbanisation by introducing displaced elements to related activities.

This is, in part, how many Wicklow names began to surface alongside the merchants and traders in Dublin after 1660. The Byrnes of Wicklow were prominent amongst them. In fact, the most common native surname of the indigenous business community in Dublin between the 1730s and 1911 is Byrne (or derivatives). Their relatively high number in 1738, compared to all others, probably reflects an early entry into the city from nearby County Wicklow.

We know, for example, that the widow of a man named Walter Byrne of Dublin claimed for and was granted an estate for life under a settlement as early as 1682; and in the 1690s, Sir Gregory Byrne claimed for plots and houses in the city.

Some sept members became remarkably wealthy. For example, about the middle of the 18th century one Edward Byrne, whose background was relatively modest, married into the wealthy McCarthy merchants of Bordeaux. In time, Edward became the richest merchant of Dublin.

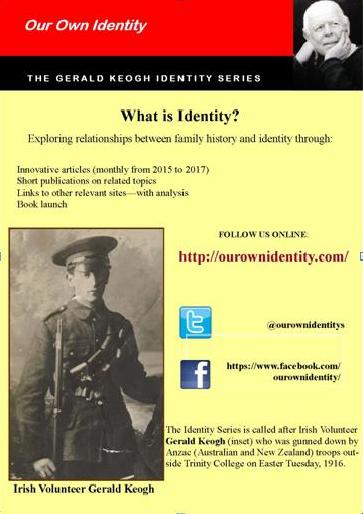

Keoghs

Another surname from Wicklow and Wexford is Keogh (or Kehoe). It ranks roughly in 20th position within the principal Irish trader surnames in the city between the 1730s and 1911. Prior to their exodus from the land they performed the principal role in the ceremonial investiture of the kings and lords of Leinster and it is widely acknowledged that they had been petty chiefs and hereditary bards to the O’Byrnes.

More research needed

The Keoghs were a minor sept compared to the ruling O’Byrnes and O’Tooles who—between them—dominated the uplands of Wicklow before their demise in the 17th century. It is surprising, therefore, that the O’Tooles rank even lower than the Keoghs relative to other native trader surnames in the city. This shows that more work is required before we know, precisely, how the process of migration out of Wicklow and subsequent urbanisation in Dublin took place.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page