ARKLOW’S 1914-1923 EXPERIENCE: Part 1 | Arklow post 1916

Arklow post 1916

This is the first instalment in a series of seven articles looking at how the immensely important decade spanning 1914 to 1923 played out in Arklow. Arklow was arguably the most industrialised town in the county, with Kynoch munitions factory being a particularly significance presence. The number of Arklow men who made their living at sea, with the resultant appalling loss of life to German u-boats and seas mines shows another aspect to that terrible time.

The difficulty with focusing on a particular era is where to start. To begin this story on 1 January 1914 would be logical, but life isn’t that clear cut. For this reason, I have attempted to give a general background to what was happening in Arklow before New Year bells heralded 1914.

Over the next year or so, further instalments will appear in the pages of http://www.countywicklowheritage.org/ until we reach 1923 and gradual settling in of an uneasy peace in a partially independent Ireland.

Background

The first decade of the twentieth century saw Arklow and its environs riding the crest of an economic wave. The fishing fleet, despite periodic ups-and-downs, was engaged in its annual exodus to west Cork from mid- March to the end of May in search of mackerel, immediately after which they followed seasonal shoals of herring up the Irish Sea and around to the east coast of Scotland. The trading fleet too was enjoying the benefits of increased general business. Ashore, the boatyard of John Tyrrell & Sons, which had long been recognised as producing top class examples of the shipwrights’ art, provided constant employment for carpenters and associated crafts. A mile south of the town, Parnell Quarries were producing kerb stones, road building material and huge lumps of dolerite rock for coastal protection works, as it had been doing since the 1880s. On the north side, the Ticknock Brick & Tile Works was also giving employment.

By far the biggest contributor to the town’s wealth, however, was Kynoch Limited, establshed in 1895 to supply explosives to mining companies. Within four years of Kynoch’s opening, it became clear that the wartime demands of the British government, then engaged in the Second Boer War (1899-1902), were to prove far more profitable. The end of the hostilities in South Africa saw the factory revert to peacetime products, but an important precedent had been set. In peace or war, Kynoch’s was a very successful company employing hundreds of men, women and teenage boys and girls.

In October 1910, Arklow Town Commissioners became Arklow Urban District Council, allowing for the first time elected local representatives to raise funds through rates.

On the political front, County Wicklow had the highest percentage unionist population outside the north-eastern counties. This was especially true of the urban areas along the coastal strip. In the 1880s and 1890s, political, religious and cultural divisions had made Arklow a by-word for sectarianism.[1]

A great deal of healing had taken place over the following twenty years, but old grievances were never too far beneath the surface. Clashes between Catholics and evangelical Protestants; between employers and embryonic trade unions; between Conservative Tories and Nationalists were still periodically reported in the Wicklow People (nationalist) and Wicklow News-Letter (unionist). If one sectar of the community organised a sports day, the chances are the other would follow suit, making every effort to clash. If Unionists turned out to welcome royal navy ships into the bay, Nationalist did their best to keep as many of the population away as possible.

The great dividing concern was Home Rule, and by the time the Third Home Rule for Ireland Bill was passed in 1912, the political tensions in Arklow reflected those of the rest of the country. The two year moratorium – it was not to be introduced until 1914 – did nothing to ease the growing animosity, it simply gave both sides time to prepare for a confrontation that seemed inevitable.

1914

Northern loyalists formed the Ulster Volunteer Force in January 1913 to resist the introduction of Home Rule by violence if necessary. Nationalists formed the Irish Volunteers in November 1913 to ensure that Home Rule would be introduced as established by law.

By July 1914, Home Rule was still not in place and the 180,000 Irish Volunteers countrywide were getting restless. Under Glenealy man Christopher M Byrne’s leadership, companies sprang up from Arklow to Bray and the ‘great majority of the male population in East Wicklow was either in the Volunteers or supporting them.’[2] The Arklow company was raised in May.[3] One of the first to join was 19-year-old Matthew J (Matt) Kavanagh. Meetings and drill sessions were held at the Boys’ National School on Coolgreaney Road. The instructor was Pa Byrne, a retired British army sergeant, who also organised route marches.[4] On 7 June, they paraded through the town and ‘a large number’ of young men signed up. Within a fortnight, this ‘large number’ had swelled to ‘an extremely large number’.[5].

James Kavanagh from Templerainey, extreme left, helping to land guns from the Asgard at Howth. (Image: Jim Rees).

At first, all they had to train with were wooden guns. At least one Arklow volunteer, James Kavanagh from Templerainey, took part in the landing of guns and ammunition from the yacht Asgard at Howth on 26 July.[6] More weapons and ammunition were landed a week later just twenty miles north of Arklow at Kilcoole.

On the international front, the growing feud between Germany and Britain made war seem inevitable. On 3 August, just two days after the Kilcoole landing, leader of the Irish Party at Westminster John Redmond offered the British government the support of the Irish Volunteers to act as a ‘home guard’, which would release occupying British troops in Ireland to fight in Europe. For some volunteers, this was a worrying move. They had joined to bring about political separation from Britain, not become an auxiliary unit of the British army. These men, however, were very much in the minority and most Volunteer companies throughout the county supported Redmond’s offer. Local unionists welcomed the move with wary acceptance.[7] Irish Volunteer marching and drilling practices became more public and began attracting sightseers.

The British government spurned the offer.

Britain declared war on Germany and Austria on 4 August and Home Rule was shelved, the British refusing to grant one small nation very restricted freedom as it supposedly went to war for the ‘Freedom of Small Nations’.

In mid-August, E C Walshe, Arklow U.D.C. chairman urged all young Arklow men to fight for Britain against ‘the common enemy’. He was roundly applauded in the chamber. Colonel Montmorency, Inspector General of the Irish Volunteers, repeated this call to Arklow men on 19 August when he inspected the 200-strong Arklow company.[8] Headed by the band of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, they marched through the town to Parade Ground, where Montmorency reminded them that they ‘had been formed to defend Ireland from her enemies’, but miraculously the British and the U.V.F. were no longer the enemy, Germany was.

Late August and early September saw the town become heavily garrisoned to protect Kynochs which now went into full-time production of munitions. An auxiliary temporary barracks, capable of housing thirty-five constables, were set up within the Kynoch complex. The coastguard station at the Seabank was also requisitioned to accommodate more troops.[9]

Meanwhile, the Volunteers were training, some with real weapons, with the promise of more to follow.

On 20 September 1914, companies of Volunteers from Rathdrum, Aughrim, Greenane, Avoca and Arklow mustered at Woodenbridge to be inspected by Colonel Moore. History was about to be made. John Redmond ‘just happened’ to be in the area on his way to his rural retreat, the old military barracks at Aughavannagh. He had stopped at Woodenbridge hotel with his wife for refreshments when the large assembly of volunteers across the road was brought to his attention. He decided to address them. Or so the story goes.

Is such a remarkable coincidence credible? No, it isn’t. It was stage-managed.

The previous week the Wicklow People had mentioned the upcoming inspection and that Redmond ‘will in all probability have an important pronouncement to make’ there. Reporting on the event the following week, the same paper said that ‘as it happened’ Redmond was in the area by coincidence.

Matt Kavanagh later recalled that Redmond arrived accompanied by Con MacSweeney, a schoolteacher in Aughrim.[10]:

John Redmond rode into the field on a white horse and addressed the assembly … he thought we would serve the cause of Ireland better by fighting on the fields of Flanders. As a result of his speech, practically all the men dropped their rifles in the field and walked away. I dropped my rifle there on the ground. I had no more connection with the Redmond Volunteers.[11]

Matt Kavanagh, and perhaps even a few others, might have walked away, but the vast majority of Irish Volunteers in south Wicklow, and 170,000 of them nationwide, sided with Redmond, many enrolling in the royal navy and British army. The majority became the National (rather than the Irish) Volunteers, but are often referred to as Redmond’s Volunteers.

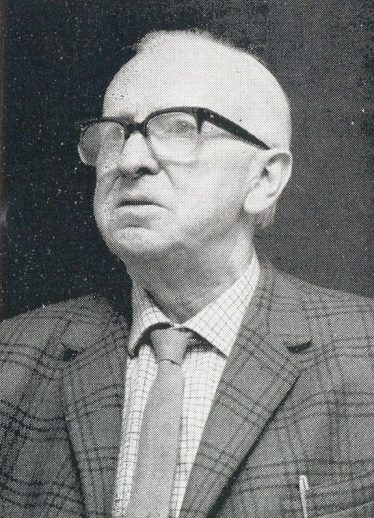

Matt Kavanagh,(1895 – 1973) Arklow Company Captain, later Commandant of the IRA East Wicklow Brigade. (Image: Jim Rees)

Initially, the rush to the recruiting office in Arklow was conspicuous by its absence. Fifty reservists had been called up in early September and had been despatched to the front. A Mrs Connold of Clifton House, offered £1 to each of the first ten Arklow men to enlist in the British forces, but again there was no immediate take-up. Likewise, an army car resplendent in recruitment posters and banner passed through Arklow, offering young men ‘a joy ride’ – the actual term used – to the nearest recruiting office, but even the novelty of a trip in a motor car failed to spark enthusiasm. Slowly, however, Arklow men did start joining up – the first ten making sure to collect Mrs Connold’s £1 bounty.

The war in Europe had already impinged on Arklow consciousness in other ways. Although some Arklow seamen were in the royal navy, the vast majority were in the merchant marine. Arklow schooners Vindex, James Postlethwaite, and Kestrel were seized in Hamburg and their masters and crews interned for the duration.[12] Local vessels such as Jane Williamson, Detlef Wagner, Ethel, Jewel, Twig, and Violet would be sunk by u-boats, taking their Arklow crews to the bottom, affecting both unionist and nationalist homes alike. For some reason, these men have not been included on the war memorial at Woodenbridge, but they are remembered in Arklow Maritime Museum. Given such losses of local life and livelihood in this maritime town, perhaps it is not surprising that any anti-British (and by implication pro-German) elements such as unrepentant Irish Volunteers decided to keep their heads down.

The town was placed under martial law, with greatly increased R.I.C. and British military presence, as well as armed patrol boats in the bay, which had been drafted in to protect Kynoch munitions factory from attack. Apart from the troops in the military camp, every publican had to accommodate three soldiers each although, as will be seen, this measure does not seem to have been implemented. Local opening hours for pubs were restricted to 10a.m. to 2p.m. and 5p.m. to 10p.m. Fishermen were not allowed to enter or leave the port in hours of darkness nor could they fish within five miles of the shore.[13]

Few Irish towns could claim to have been so locked down. Little wonder that the greatly reduced Arklow Irish Volunteers were quiet from 1914 to 1917.

Footnotes

[1] For a comprehensive study of the period see Jim Rees, Split personalities, Arklow 1885-1892, (Arklow, 2012).

[2] Christopher M. Byrne, Bureau of Military History (BMH), Witness Statements (WS) 1014, p.1.

[3] Wicklow People, 23 May 1914.

[4] Matthew J. Kavanagh, BMH, WS 1472, p.1. He recalled the formation of the company as being in April rather than May.

[5] Wicklow People, 27 June 1914.

[6] Cairns, Henry and Gallagher, Owen, Aspects of the War of Independence and Civil War in Wicklow 1913-1923, (Bray, 2009), p.2.

[7] Ibid, p.5.

[8] Wicklow People also refers to him as Major Montmorency elsewhere.

[9] Wicklow People, 5 Sept 1914.

[10] For details of MacSweeney’s life see Noel Ó Cléirigh, ‘Major Conn MacSweeney’ in Wicklow Historical Society Journal 2015, pp.28-39.

[11] Matthew Kavanagh, BMH, WS 1472, p.1.

[12] For the war experiences of Arklow seamen see Frank Forde, Maritime Arklow (Dun Laoghaire, 1988), pp. 172-186.

[13] Hilary Murphy, The Kynoch Era in Arklow, (Arklow, n.d. but c. 1975), p.44.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page