ARKLOW’S 1914-1923 EXPERIENCE: Part 2 | 1915-1917

This is the second instalment in a series of seven articles looking at how the immensely important decade spanning 1914 to 1923 played out in Arklow. Arklow was arguably the most industrialised town in the county, with Kynoch munitions factory being a particularly significant presence. The number of Arklow men who made their living at sea, with the resultant appalling loss of life to German u-boats and seas mines, shows another aspect to that terrible time.

Further instalments will appear in the online community archives of Our Wicklow Heritage until we reach 1923 and the gradual settling in of an uneasy peace in a partially independent Ireland.

1915

In 1915, the behaviour of the British royal navy at the scene of the sinking of the Lusitania angered many Arklow people. In May of that year, Arklow fishermen were again observing the fishing seasons and were operating around Kinsale in County Cork. On the 15th of the month, the passenger liner Lusitania was torpedoed just a few miles off the Old Head of Kinsale with the loss of 1,129 lives. Edward White and James Hagan, captains of the Elizabeth and Dan O’Connell respectively, immediately put to sea to render what assistance they could. Hagan’s boat was the first to reach the survivors, about forty of them in one of the Lusitania’s lifeboats. He put one of his men on board to pilot them safely ashore while he headed towards the wreck area.

… such a scene was impossible to describe. There were about twelve boats picking up the living and the dead while the first boats were returning to land survivors.[1]

This rescue work was impeded by the royal naval tug Stormcock:

Edward White, the skipper of the Elizabeth, was off the harbour mouth of Kinsale when Commander Shee of the Stormcock halted him and ordered him to hand over his survivors. White protested, as did Jimmy Hagan of the Dan O’Connell, that there were others waiting for rescue at sea. Some of the women on board, said White, were in a bad way; he wanted to get them to Kinsale as quickly as possible. But Shee threatened; ‘If you don’t stop we shall sink your boat’. The Elizabeth’s boat from the Lusitania was taken in tow by the Stormcock which headed back for Queenstown. Not only had time been wasted, White reckoned, but lives would be lost by the Stormcock’s action.[2]

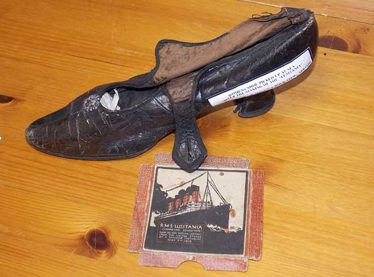

This event and the role played by these Arklowmen is commemorated with a special display in the Arklow Maritime Museum:

Shoe found in the nets of James Hagan’s steam drifter Dan O’Connell a few days after the sinking of the Lusitania, having been left behind by a survivor only too relieved to reach dry land. (Catalogue number 119: Arklow Maritime Museum).

More pro- than anti-British

The number of Arklow men fighting in Flanders and elsewhere or sailing in the ships of the royal navy still prompted the majority of Arklow people to be more pro- than anti-British at that time. Neither should it be forgotten that Kynoch explosives factory was once again geared towards the production of munitions for the British war effort and the work force had risen to 4,000.[3]

Few families did not have at least one member working in the vast complex, many had two or three family members there, and the revenue generated by rates paid to Arklow Urban District Council was making it possible to finance urgently needed social housing and other projects. It is hardly surprising that interest in a military rebellion to establish Irish independence was little more than a vague idea in the minds of an increasingly isolated few.

1916

When the Easter Rising broke out in Dublin and a few other pockets around the country in April 1916, County Wicklow did not take part. In fact, the only company of Irish Volunteers that was still active was in Bray. This company was comprised of thirty-five men, all of whom except three, obeyed Eoin MacNeill’s command not to muster.[4] Seamus O’Brien in Rathdrum, and a few more dotted throughout the county, ignored MacNeill’s orders and made their way to the capital to take part in the Rising.

The only action being taken in the Arklow area, despite the heavy security at Kynoch’s, was the smuggling of percussion caps out of the factory in quantities sufficient to last right through to the end of the War of Independence. Even this level of activity is surprising when the presence of a greatly increased R.I.C. contingent and a large camp of British soldiers adjacent to the factory are taken into consideration. As soon as the Rising in Dublin was over, even more troops were drafted into Arklow by train from various regiments to prevent an attack on Kynochs. The Masonic Hall was commandeered as a temporary barracks for these extra troops; sentries with fixed bayonets stood at the ends of most streets and at the bridge; guns were placed on some public buildings.[5]

Enniscorthy Volunteers

Yet an event, small itself but worth recording here, did take place at Arklow harbour in May, following the surrender of the insurgents in Enniscorthy.

The volunteers in Enniscorthy held out longer than anybody else in the country, and did not surrender until they received orders sent by Pádraig Pearse who was already in custody in Dublin. When they gave themselves up, they were brought to Arklow by lorry under heavy escort and lodged in one of the temporary military barracks where they were kept overnight. The Ticknock Brick & Tile Works, immediately behind the Coast Guard station at Seabank, was by this time being used to accommodate some of the British troops and it was there that the Enniscorthy men were held. The exact number of prisoners is uncertain, one source says thirty-six another says twenty-eight.[6]

The following day, at about six in the evening, they were marched in handcuffs to the harbour and put on board the Urania, a steam trawler which had been built in Dundee in 1907 and registered in the Welsh port of Milford the same year. In December 1914 she was commandeered by the admiralty (No.960), fitted with a six-pound gun, and used as a minesweeper in the approaches to Milford Haven.[7] Redeployed for this particular task, she took the men to the North Wall in Dublin from where they were marched to Richmond barracks before being sent to Frongoch internment camp in Wales. What concerns us here is the quayside scene in Arklow as they were being led to the Urania:

A considerable number of Arklow people, men, women and children, lined the route and cheered us loudly. This surprised us as most of the men in Arklow had been working in Kynoch’s munitions factory and some [were] in the British navy. The British officer was very vexed with them cheering us and threatened them with a revolver, and had his men put back the crowd with bayonets.[8]

This small incident is significant as it shows the mixed feelings prevalent in Arklow. It stood in marked contrast to the reception these men received from the people of Dublin who ‘showed great hostility towards’ them as they were marched to Richmond barracks from the port area and again on their return journey.[9]

1917 – Re-establishment of Volunteers in Wicklow

In the aftermath of the Rising, the execution of the leaders and the internment of volunteers (including the imprisonment without trial of many innocent individuals), public attitudes towards the nationalists’ cause changed. The time had come to re-establish the Irish Volunteers throughout the county. Christopher M Byrne was one of the principal driving forces, just as he had been when the Volunteers were first proposed in 1914. East Wicklow Brigade was divided into two battalions, the 4th and 5th, the latter covering the southern section:

EAST WICKLOW BRIGADE:

Commandant Seamus O’Brien, Rathdrum

Tom Cullen, Wicklow Town, Vice OC

The 5th Battlion (Jim O’Keeffe, OC.): Battalion G.H.Q. were at the Forestry Department’s premises at Avondale, where O’Keeffe was a student.

Companies (Company Captains)

- Arklow (Martin Redmond replaced by Matthew Kavanagh),

- Avoca (Bill Tracey),

- Barndarrig (Jimmy Doyle),

- Johnstown (Will Kavanagh),

- Glenealy, Rathdrum (Paddy Curran).

According to Matt Kavanagh, the Arklow company was re-formed by Christopher M Byrne in October 1917.[10] Martin Redmond was appointed company captain, but he emigrated to America soon after and Matt was promoted to replace him. Seventeen-year-old John Kavanagh of Gregg’s Hill, no relation to Matt, was 1st Lieutenant. John Kavanagh was a remarkable individual who had fought in Dublin during the Easter Rising when only sixteen years old. He will figure later in this story. The meetings of the Arklow company were held in Maggie O’Toole’s house. She was a member of Cumann na mBan.

There was also a strong branch of the Irish National Aid in the town. Finance for this was raised locally by Paddy and Ned Redmond. Paddy had been an officer in Redmond’s National Volunteers. They collected weekly on pay day outside the gates of Kynoch’s and were quite successful, but this was not directly Irish Volunteer business.

There was not much activity in the Arklow company or Wicklow brigade area during 1917 and 1918 other than propaganda work – distributing literature, posting up bills, etc – and trying to accumulate stocks. We collected the ingredients for making gun powder from local chemist shops, and we collected lead for making buckshot. We were actually making pikes as well. Some of the pikes were made by a chap called Mooney, a blacksmith in Avoca.[11]

Andrew Kavanagh from Ferrybank, no relation to either Matt or John as far as I can determine, joined the company later in the year, while still only sixteen.[12] There were three or four others of the same age and all were deemed too young to take part in anything except minor actions although, from Matt Kavanagh’s statement above, all the actions at that time were relatively minor. John Kavanagh would also have been in this younger cohort, but he had experienced action in Dublin the previous year and perhaps should not have been deemed ‘too young’ for more serious activities. Andrew mentions arms raids on houses which netted a few shotguns, and seizing and burning British newspapers. These would arrive by train and the Arklow company would pick a station within a ten or twelve mile radius. While the R.I.C. watched one, they would raid another. It was obviously of more nuisance and propaganda value than military coup. Andrew Kavanagh left Arklow a few months later to work in Newbridge, County Kildare and later in Nenagh. He would return to Arklow in 1919, more mature and eager to take on greater responsibility.

Explosion at Kynoch’s Munitions Factory

The most memorable event in Arklow in 1917 was to endow Kynoch’s with an almost mythical status in the Arklow community – ‘The Explosion’. There had been several fatal accidents prior to this; the more recent included one in 1910 which killed two workers pushing a bogey containing ten boxes of Arkite paste, the company’s own brand of high explosive; a small explosion killed two more the following year; and two buildings near Spion Kop were blown to bits in 1915.

Kynoch’s munitions factory which extended for over a mile along North Beach. (Images: Jim Rees).

In the early hours of 21 September, 1917, about 200 men and twelve girls were working the night shift. At half past three, the guard at the main gate was changed and Pte Richard Craig of the Munster Fusiliers began his watch that was scheduled to end at six. Within fifteen minutes of his taking up his station, a brilliant flash lit up the countryside, followed in a second or two by a deafening explosion. Townspeople were thrown from their beds, windows were shattered and the blast could be heard up to twelve miles away. Fr Purfield, a local curate, dressed as quickly as he could and hurried towards the factory. Scores of people, many still in their night clothes, were running across the bridge, frantic for news of relatives and friends.

When they reached the scene, they were confronted by a horrifying spectacle. Several bodies lay in varying degrees of mutilation. Clothes and boots had been blown off and lay scattered among the myriads of broken glass. Four huts, each housing men mixing nitroglycerine and guncotton, had exploded. Three of the huts had vanished completely, leaving only a crater where they had stood. The fourth was a broken shell. A search was made through the rubble for more bodies, several were discovered. The injured, some horribly so, were taken to the factory’s small hospital.[13] With the coming of dawn, the searchers began removing the debris, including the pieces of flesh which was all that remained of some of the victims.

What had happened? No one knew, but an inquest was started within days.

Colleagues, relatives and friends of the dead and injured filled the large recreation hall in the factory grounds where the inquest was to be held. The building was unable to accommodate all the on-lookers and many were forced to follow the proceedings by looking and listening through the windows. At the head of the room sat two company directors and a representative of the Home Office, Major Cooper Key. The company manager, Mr Udal, stated that he first heard a hissing or tearing sound followed by three distinct reports only a fraction of a second apart. It could, he felt have been an attack from the sea, the shoreline being only a few hundred yards away and u-boats had been active in this area. In fact, a u-boat had sunk the South Arklow lightvessel on 28 March that year, just six months before the explosion in Kynoch’s.[14]

Cooper Key was disinclined to accept that theory as he felt the time factor between the first and third reports would have been longer than a fraction of a second had shells been fired from the deck gun of a submarine from a reasonable distance, say four thousand yards. Both Pte Craig, who had been on guard duty at the main gate which was in close proximity to the scene of the explosion, and George Harvey, captain of the patrol boat in the bay, also believed an attack had not been made from the sea.[15] To make matters even more confused, other witnesses maintained that the lights of a car had been seen in the vicinity just before the explosion. A buzzing, drumming sound in the air was also heard.

Could it have been an attack from land by the I.R.A.? On the other hand, couldn’t the explosion have been caused accidentally? As we have seen, it was an extremely dangerous environment in which to work.

Several reliable witnesses testified that all safety precautions had been adhered to. One foreman had been in the ill-fated houses fifteen minutes before the blast and he had seen nothing to indicate lax security measures. It was pointed out that for some weeks before the catastrophe several employees had been found in possession of matches on the premises, but Mr Udal was quick to counter that no one in the danger houses had ever ignored these particular regulations. With such lack of hard evidence and a plethora of conflicting opinions, a verdict of unknown causes was returned.

A total of twenty-seven men were killed that night. In Arklow cemetery, a monument commemorates those who died in the explosion. Their names, ages, and places of residence show how important Kynoch’s was to the general area; of the twenty-seven victims only four were from the town. Two were from Blessington, two from Tinahely, two from Hacketstown, two from Shillelagh, two from Enniscorthy, and one each from Wicklow, Dalkey, Knockananna, Gorey, Craanford, Ballycanew, Cronebeg, Woodenbridge, Rathdrum, Barniskey, Redcross, and one from county Cork. Oddly, the monument lists only twenty-six names although most accounts give the number of deaths as twenty-seven.

The deaths of twenty-seven young men in such frightening circumstances were bound to leave an effect on the town in general and on the factory in particular. The question which played on everyone’s mind was, what would have been the outcome had the explosion taken place at half past three in the afternoon, when the full workforce was milling about that area? How many hundreds would have died? How many irreparably maimed? But life goes on. Food must be put on the table. As long as the war lasted, production targets had to be met. As long as wages were offered, worries had to be reined in.

The story of the explosion was planted in the fertile soil of local lore where it grew lavishly. After a few decades many who heard about it at firesides or public house counters formed the impression that the bulk of the factory had been devastated and that Kynoch’s had little option but to bring down the curtain on this tragedy. But that is not the case. The factory was back in production within a day or two. After all, there was still a war on.

German torpedoes

That year also saw Arklow schooners and their crews attacked by German torpedoes and gunfire, resulting in loss of life. The last and one of the most poignant of these losses was the Lapwing. She sank with the loss of all hands after hitting a mine off the Suffolk coast in 1917. Among the victims were the master Joseph Kearon and his two sons Edward and George.[16] They lived in ‘Kylemore’ near St Saviour’s church.[17]

With such sad tales and a German navy to focus on, republicanism was not high on Arklow’s agenda.

[1] Quoted in Forde, Maritime Arklow, p.174.

[2] ibid. p.176

[3] See Jim Rees, Arklow, the story of a town, (Arklow, 2004), pp. 248-259.

[4] Cairns & Gallagher, p.9.

[5] Wicklow News-Letter, 6 May 1916.

[6] Compare Patrick Ronan, Bureau of Military History (BMH), Witness Statement (WS) 299, p.4 with John J. O’Reilly, BMH, WS 1031, p.13.

[7] My thanks to Pat Power for bringing this to my attention. For details of the Urania http://www.llangibby.eclipse.co.uk/milfordtrawlers/accidents%20&%20incidents/urania.htm 20 July 2015.

[8] O’Reilly, BMH, p.13

[9] Ronan, BMH, p.5. I could find no reference to it in the Wicklow People, but the Wicklow News-Letter did mention it (6 May, 1916) but said nothing of the officer’s reactions and threats.

[10] Matthew Kavanagh, BMH, WS 1472, p.1.

[11] Ibid., p.2.

[12] Andrew Kavanagh, BMH, WS 1471, p.1.

[13] This later became the Countess of Wicklow Memorial Hospital and stood on the site now occupied by the Arklow Bay Hotel.

[14] Frank Forde, Maritime Arklow pp.295-6; Also Roy Stokes, ‘The South Arklow lightvessel has disappeared’ http://www.countywicklowheritage.org/page/the_south_arklow_light_vessel_has_disappeared 23 July 2015.

[15] For a sequel to this event see Jim Rees, ‘Unsolved mystery of World War 1’ in An Cosantóir,June 1985, pp.205-6.

[16] Forde, Maritime Arklow, p.184.

[17] For more information about the losses of Arklow lives at sea during this time, see the special display in Arklow Maritime Museum.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page