ARKLOW’S 1914-1923 EXPERIENCE- Part 5 | July- December 1920

This is the fifth instalment in a series of articles looking at how the immensely important decade spanning 1914 to 1923 played out in Arklow. Arklow was arguably the most industrialised town in the county, with Kynoch munitions factory being a particularly significant presence. The number of Arklow men who made their living at sea, with the resultant appalling loss of life to German u-boats and seas mines, shows another aspect to that terrible time. Over the next year or so, further instalments will appear in the pages of Our Wicklow Heritage until we reach 1923 and the gradual settling in of an uneasy peace in a partially independent Ireland.

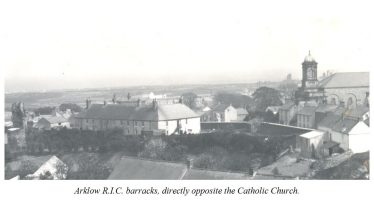

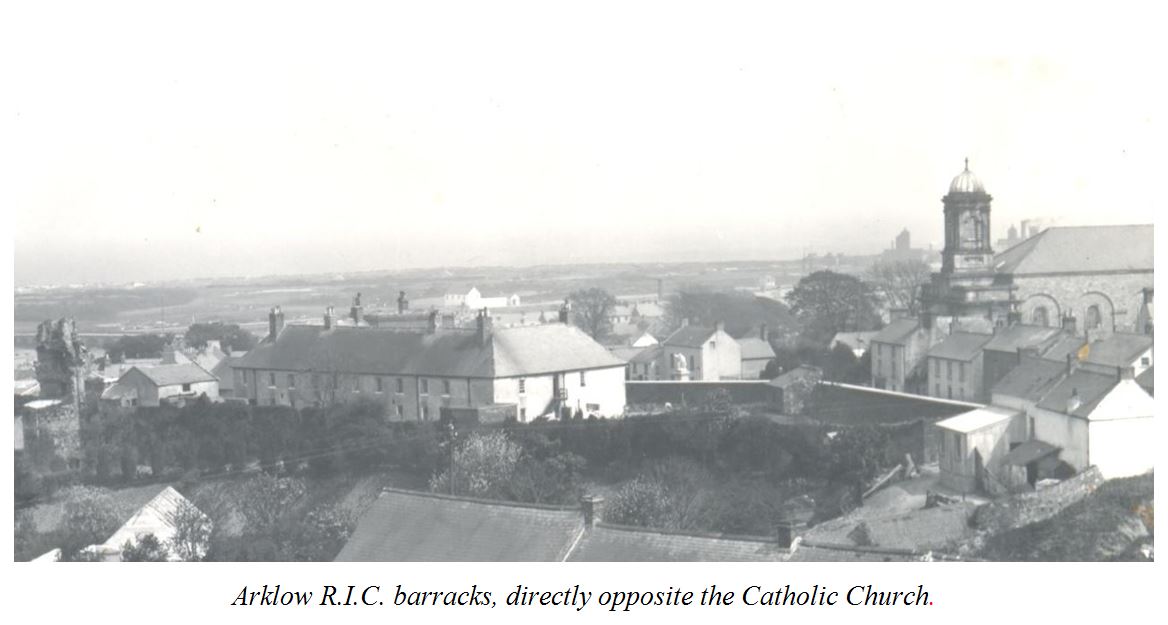

By mid-1920 there were about eighty R.I.C. men in the barracks on Parade Ground and ‘half a company’ of the Sussex Regiment in a temporary military barracks.[1] Despite this presence, the I.R.A. companies in the Arklow area continued to be active, destroying abandoned barracks at Aughrim and Redcross and burning huts used by British soldiers in and around the Kynoch complex.

In July, five such huts were heavily doused in petrol and set alight. They had been used by members of the Cheshire Regiment who had been transferred a few days before. Now, only one of the huts was in use by twelve Royal Engineers who weren’t present when the attack was made. Bray man David Frame had bought the complex from Kynochs in November 1919 and he brought a claim for malicious damage for the amount of £5,000. He was awarded £3,000.[2] In October, they carried out another raid on Kynoch’s, netting 25 cwt of TNT, which was put in a car and conveyed to Dublin.

Extract from Andrew Kavanagh’s witness statement:

Since his return from Liverpool, Andrew Kavanagh was

whole time engaged on Volunteer work going with despatches to the Captains of the various Companies in the battalion and also acting as courier to a guard on the railway who brought despatches to and from G.H.Q. He was on the Shillelagh line and did not come to Arklow at all. I was constantly engaged on that. During a raid on Avoca Manor House we captured some obsolete revolvers and a small keg of blasting powder which we seized and dumped nearby. We arrived home early in the morning. Next day we returned and commandeered a car at the Valley Hotel. The driver, Mr. Jackson, Carlow, drove us back into town with our booty, the keg of blasting powder which we [had] dumped.[3]

It was about this time that Tom Quigley ceased to be Brigade Adjutant and Andrew Kavanagh was appointed as his replacement. This meant that by the end of autumn of 1920, the two main positions in East Wicklow, Brigade OC and Brigade Adjutant, were both held by Arklow men.[4]

Four attacks

As well as the above activities, there were also four attacks on Arklow barrack during the year. The barrack had been built in around 1720, was well positioned in the centre of the town and was sturdy enough to resist any attack that the local Company could possibly mount. Because of the number and strength of police and soldiers in Arklow, and because of the way in which the barracks stood well back from its twelve foot high perimeter wall, an open attack would have been suicide. Instead, pipe bombs were thrown over the wall. These were made by Matt Kavanagh from short lengths of rain water pipes and metal boxes off cart wheels. Gelignite, unwillingly supplied by Kynoch’s, was stuffed into these and the ends sealed with wooden plugs, through one of which a small hole was drilled for a fuse. The barrack stood directly across from the Catholic church and this helped determine when a pipe bomb attack should take place. Although it meant danger to the general public, it was thought that an attack should be launched when there were a lot of people milling about. In that way, the attackers could blend in with the crowd rather than having to make their escape across open ground.

Matt Kavanagh’s words:

The time selected for these minor attacks was when the people were coming out from Sunday evening devotions. On the occasion of the first attack we used a cart wheel box bomb. The man who was selected, especially because of his height to throw it, was Myles Cullen, Captain of the Ark1ow Company. [Presumably, Cullen had been promoted when Matt Kavanagh became Brigade OC in February.] He had previously practised throwing stones of similar weight. When Cullen threw the bomb it struck the top of the wall and came back among the congregation. Cullen had to take it with the fuse still burning and throw it again. We came to the conclusion that a wheel box bomb was too heavy for throwing any height or distance and discontinued making them. We then concentrated on the rain water pipe type … The first three attacks were carried out by seven or eight men each time. One man threw the bomb and the remainder, who were armed with revolvers, acted as a covering party, and to warn civilians to keep clear.[5]

Perhaps worried that civilians might be injured, a new tactic was adopted for the fourth and last attack on the stronghold:

The last attack on the barrack was made by Jack Holt and myself on the main gate. We placed a rain pipe bomb underneath the main gate at about 10 o’clock one night. Having lighted the fuse we ran for cover but the fuse went out and we had to light it again. Before we succeeded in getting round the corner for cover we were blown down by the force of the explosion. The R.I.C. came out through a smaller gate and fired at random through the town. The following night they came in uniform and wrecked my home. They looted the shop, taking everything in the window. This was my home and the residence of my aunt, Maria Curran, who was Sinn Féin chairman of the Arklow Urban District Council.[6]

The extent of the damage done to the barracks was negligible, and the courts awarded the Receiver for the R.I.C. £30 the following January.[7] Such harassing operations meant that the Arklow Company was ‘responsible for making it imperative for the British forces to have garrisons in Arklow, Rathdrum, Wicklow and Kilpedder’, making it impossible for the British to deploy these troops to other parts of the country.[8]

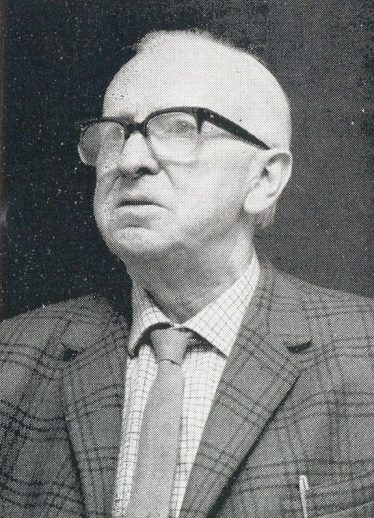

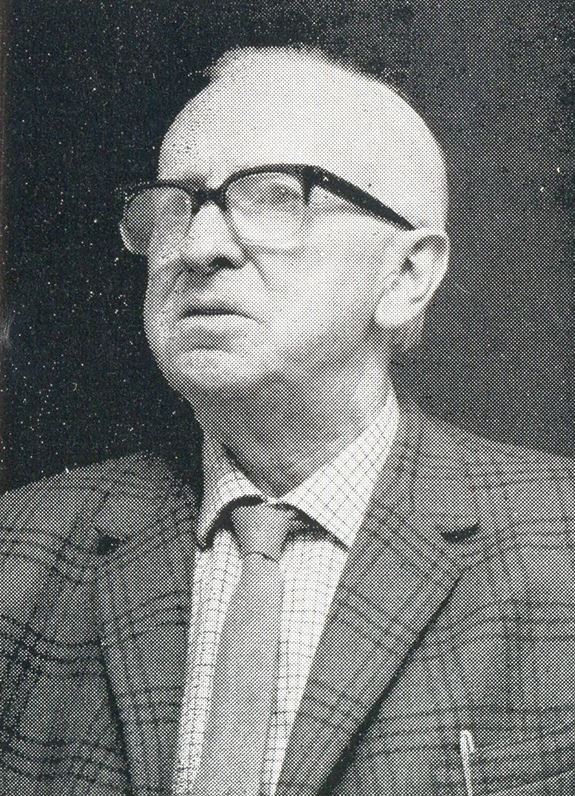

Matt Kavanagh,(1895 – 1973) Arklow Company Captain, later Commandant of the IRA East Wicklow Brigade

Raid on Kynoch’s Munition Factory & Michael Collins’ promise

On 13 November, thirteen hundredweight of TNT was taken in another raid on Kynoch’s, and much of the remaining stock destroyed by emersion in the river. This action was also initiated by Joe Kelly who reported the presence of the explosive. Those involved were Leo and Jimmy Fitzgerald (from Dublin) and locals Michael Mulligan, Mickey Greene, Anthony Kavanagh (not to be confused with Andrew Kavanagh), Joe Kelly, Robert Tyrrell (Mahon’s Lane), Paddy O’Brien and Jack O’Brien.[9]

Most of the haul was dispatched to Dublin and a few days later, Michael Collins, perhaps in appreciation of the TNT, fulfilled a promise he made to Matt Kavanagh by sending ten grenades and 125 rounds of ammunition to the Arklow company. It was another coup in which no one was injured.[10] There were, however, casualties in other parts of the country and Arklow Urban District Council passed a resolution in sympathy with the families of I.R.A. men who had been killed. As a result of this, the council offices were raided.

Black and Tan presence

The increased activity in the town and environs couldn’t be allowed to go unchecked. As Brigade OC, Matt Kavanagh had been spending a lot of time at G.H.Q. in Dublin as well as organising and taking part in raids in Arklow. On one occasion, his superior officer in G.H.Q. warned him not to return to Arklow because the Black-and-Tan presence had been increased in the town and they were looking out for him. Staying out of Arklow was a luxury Kavanagh felt he could not afford as he had planned a brigade meeting, preparations for which needed to be carried out and so he returned despite the risk involved. Notes alerting the various company captains to the planned meeting had to be drafted and copied. Each note was addressed with just the words, ‘O.C., Arklow’, ‘O.C., Johnstown’, etc., with no individuals being named. This work was being carried out on 14 December in the Arklow H.Q., in Joe Rafferty’s pub. Present were Matt Kavanagh, the Brigade Adjutant Andrew Kavanagh, and Arklow Company Adjutant Paddy Kelly, ‘when the place was surrounded by soldiers of the Sussex Regiment.’[11]

Taken into custody – possible spy?

The three men and the papers in their possession were taken into custody. Matt Kavanagh noticed that some of the soldiers was improperly dressed, wearing ‘camp slippers’ rather than regulation boots. From this he surmised that they’d had little time to prepare, as if they had been roused from their billets and were acting on information just received. The fact that there were no R.I.C. present also suggested that this was a spur of the moment response to a tip rather than a planned action. But who could have informed? Matt Kavanagh maintained that nobody in Arklow…

except [blank space in record] and my Adjutant, who was arrested with me, knew of the house we used as headquarters and also as a covering address for G.H.Q. correspondence.

This is a strange statement. Did he seriously mean that no one knew that it was the local H.Q.? That is difficult to accept. Surely the local company members knew. Didn’t the Raffertys know? Wouldn’t the tipplers in the pub, volunteers and non-volunteers alike, know? In a small town, wouldn’t half the population have known? It seems a very naïve remark. Even one of the G.H.Q. organisers had felt that the Arklow H.Q. would have been better located on a boat in the harbour rather than in such a conspicuous place.[12]

Another point, when he referred to ‘my Adjutant, who was arrested with me’ was he referring to Andrew Kavanagh (Brigade Adjutant) or Patrick Kelly (Company Adjutant)? Both were arrested with him. Whichever he meant, when the time came to ask questions about the arrests, G.H.Q. decided to take a lenient view, preferring to believe that it had resulted from carelessness in

discussing the nature of Headquarters documents in a public house to the manager of the military barracks canteen.[13]

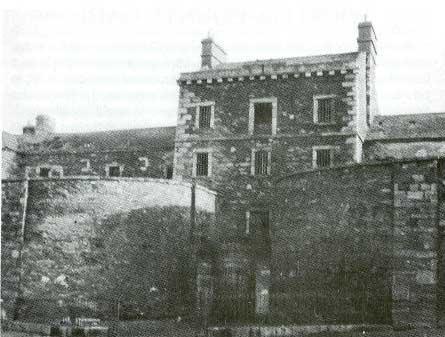

This is an even more remarkable statement. ‘Careless talk’ was bad enough, but careless talk to the ‘manager of the military barracks canteen’ should have warranted serious repercussions. Oddly, nothing happened. The three I.R.A. officers were brought to the military barracks at Arklow and interrogated but none disclosed any information. They were then transferred to Wicklow gaol. The owner of the pub and his son were also arrested but were kept in custody only until the two Kavanaghs and Kelly had been removed to Wicklow.

Wicklow Gaol pre 1950

A British trap

The British felt that they could use the captured documents to entrap all the company captains in the brigade by arranging a false brigade meeting in Barndarrig. British agents were despatched from Dublin, claiming to be attached to I.R.A. G.H.Q…..

One of the Cumann na mBan girls from Wicklow, Kathleen Treacy, whilst visiting me in the jail at Wicklow a couple of days after my transfer there, informed me that there was a gentleman going around the county wearing a Fáinne and stating that he was an officer from General Headquarters. He informed them in Wicklow town that he was sent down from G.H.Q. to reorganize the county and convene a meeting, for the purpose of appointing somebody to replace me and take reprisals for my arrest. I immediately got suspicions, as I had never notified G.H.Q. of my arrest, nor had any notice of my arrest appeared in the press and I told her to let the lads outside know and be extra cautious. Some days afterwards, I heard that this alleged G.H.Q. organizer had used the correspondence, which I had already addressed, made an effort to contact the various O.Cs. of the Companies for the purpose of convening a meeting at Barndarrig Hall of all the Company officers. It was a Brigade Council mobilisation. He actually contacted local Sinn Féin leaders in each area and asked them to transmit the correspondence to the O.C. of the I.R.A. They were instructed by circular to bring a list of the men, arms, ammunition and equipment of each Company area with them. The ruse was upset, due to the suspicions of the men.[14]

It was C.M. Byrne who was the first to be uneasy about this ‘order from G.H.Q.’. He used his understanding of the Irish psyche and our well-known penchant for unpunctuality to very good effect: ‘if they were British agents they would expect us, as military men, to be there on time, while if they were our own crowd they would not mind us turning up late.’[15] Byrne managed to get word to all the companies to turn up late for the meeting. Only the Rathdrum company captain, Paddy Curran and his adjutant Gerry Morrissey, were punished for their punctuality – arriving at the designated venue at the designated time Curran was arrested and put into the back of a lorry. Morrissey tried to make a run for it, but was captured. By the time the latecomers arrived, the British had decided that no one else was coming and departed with just the two Rathdrum men.

Reprisals – searches – arrests

They had a revenge of sorts that night when they went into Wicklow town and, getting the names of well known Sinn Féiners, W. O’Grady, U.D.C., and John Byrne, from the police, they beat them up and arrested the Chairman and Secretary of the local Sinn Féin Cumann. But their well laid plans fizzled out.[16] Andrew Kavanagh was later to state that he was still in Arklow military barracks when Curran, Morrissey and three other men (probably those mentioned above who were arrested in Wicklow) were brought in, but this is unlikely. It was more likely to have been in Wicklow gaol for several reasons. One, their arrests took place at least several days after Kavanagh’s – by which time he’d been transferred to Wicklow – and, two, they would most probably have been brought directly to the local jail. Wherever it was, Arklow or Wicklow, Kavanagh said that he recognised the third man as a spy and he warned the others.[17]

On 28 December, two weeks after the Arklow arrests had been made in Rafferty’s, a large force of military personnel and police surrounded the houses in Abbey Street and made a thorough search of every building. Despite the raid lasting ‘a considerable time’, nothing suspicious was found, but one of the residents, William Cleary, a volunteer in the Arklow company and boot maker by trade, was taken into custody, brought to Wicklow gaol and later transferred to Dublin. Other arrests had been made in the preceding weeks. Some of these detainees had been released after a short while, but others, like Cleary, were taken to Wicklow gaol.

One description of a less hostile house raid was that of Thomas Furlong’s home:

Presses were scrutinised and drawers and beds examined, as was also a statue of the Blessed Virgin. Pictures and photographs taken away, including some snaps of friends in America. As well as a newspaper and some old copies of Nationality, as well as some books and receipts of the I.N.G.W.U. Dennis Keogh, who happened to be in the house at the time, was arrested. Furlong said that the officer in charge was very courteous and allowed Mrs. Furlong and family to move about unmolested.[18]

Not all searches were carried out so cordially. Some of these were for arms, others were for people who on the run, but no specific reason was ever given. Andrew Holt, who had been on hunger strike in Mountjoy before his release, and his father John, a member of Arklow UDC, had been arrested at their house on Ferrybank and taken into custody around Christmas time, along with other men from the town and district. They were kept at the military camp in the old Brick & Tile Works but were released just before New Year. Other men from the town and district who were arrested at the same time were not released and were removed to Wicklow. On New Year’s Eve, military and police personnel paid a visit to the Fishery area where more searches were made. In the house of Michael O’Brien in Old Chapel Ground, Michael’s two young sons, Patrick and John, were arrested.[19]

Gregg’s Hill, the Fishery, Arklow

And so the year closed. It had been the most active year in the Arklow area so far. It had also seen two Arklow men being appointed to the two main positions in the East Wicklow Brigade, but also saw their arrest, along with the Arklow Company Adjutant.

The year 1921 promised to be what the Chinese refer to as ‘interesting times’.

References

[1] Andrew Kavanagh, BMH, WS 1471, p.3.

[2] Wicklow News-Letter, 15 Jan 1921, 29 Jan 1921.

[3] Andrew Kavanagh, BMH, WS 1471, p.3.

[4] Matt Kavanagh, ‘Wicklow – 1920’ in The Capuchin Annual 1966, p.590.

[5] Matt Kavanagh, BMH, WS 1472, pp.13-14.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Wicklow News-Letter, 29 Jan 1921.

[8] Matt Kavanagh, ‘Wicklow – 1920’ in The Capuchin Annual 1966, p.590.

[9] Cairns & Gallagher, p.25.

[10] Murphy, H. Kynoch Era, pp.64-5

[11] Matt Kavanagh, BMH, WS 1472, p.7. Also Andrew Kavanagh, BMH, WS 1471, p.4.

[12] Christopher M. Byrne, BMH, WS 1014, p.11.

[13] Matt Kavanagh, BMH, WS 1472, p.7.

[14] Ibid, pp.9-10.

[15] Christopher M. Byrne, BMH, WS 1014, p.12.

[16] Ibid, p.13.

[17] Andrew Kavanagh, BMH, WS 1472, pp.4-5.

[18] Wicklow People, 1Jan, 1921

[19] Ibid. 8 Jan 1921

No Comments

Add a comment about this page