A time of transition: from the 1916 Rising to the 1918 election in the Dunlavin region by Chris Lawlor

All across Ireland, the Easter Rising took people by surprise. Unionists viewed the whole event as a stab in the back to all who were fighting for King and Country in the Great War. The vast majority of Nationalists also perceived the event in this way, as huge numbers of them had joined up in the wake of John Redmond’s call to arms at Woodenbridge. However, Nationalist feelings of righteous outrage were soon replaced by a grudging admiration, as the rebels were incarcerated and their leaders were executed over a protracted period of time. These executions, coupled with the wave of arrests in the aftermath of the rising, engendered resentment and stoked the anger of Nationalist Ireland. The sheer volume of arrests, the lack of due process as suspects were incarcerated without trial and the rough treatment meted out to many of these prisoners began to change the minds and mindsets of many mainstream Nationalists, who had been supporters of the Irish Parliamentary Party and the Home Rule movement up to this point. Now, however, sympathy for the rebels’ cause, and respect for the stance that they had taken, started to grow in Nationalist communities throughout Ireland.

Compensation claims

The aftermath of the Easter Rising during the second half of the year 1916 witnessed a change in tone in the editorials of local newspapers, as the content of their articles began to reflect this swing in nationalist public opinion. Although Dunlavin was not directly affected by the rising, three of its inhabitants made claims for property lost during the fighting in Dublin. The Property Losses (Ireland) Committee was established in June 1916 to investigate claims for losses and damage to property during the rising.[1]:

- John Maguire of Crehelp, who worked as a barman in Moore’s public house at 13 Eden Quay, lost clothing and a timepiece in the conflagration. His claim for a suit of clothes, two pairs of boots, two pairs of gloves, three shirts, two caps, five collars, four pairs of stockings, an overcoat and a watch and chain came to a total of £6 18s 6d, and the committee recommended payment of £6 10s.[2]

- Dunlavin resident Rachael Brien’s claim to the committee of £1 15s for a gold wristlet watch lost on the premises of jewellers McDowell Brothers, at 27 Henry Street was eventually withdrawn, as McDowells themselves compensated her (probably via their insurance company).[3]

- Another Dunlavin lady, Emma F. Doyle, also lost a gold wristlet watch and a tortoise brooch, both of which were either burned or looted from the premises of jeweller John McDowell at Upper Sackville [O’Connell] Street. The committee recommended that Doyle’s claim of £2 10s be paid in full.[4]

These compensation claims reveal the ease of travel between Dunlavin and Dublin. The city was evidently both a place of employment and a higher order services centre for Dunlavin residents who wished to avail of many specialist services and the wider range of items for purchase than the more limited selection in the village or its neighbouring towns. Once the Tullow branch of the Great Southern and Western railway reached Dunlavin in 1885,[5] three ‘up trains’ linked Dunlavin to Dublin and three ‘down trains’ made the return journey each day. This transport link to the capital enhanced the goods and services available in Dunlavin, but it also provided a conduit for news and ideas – including political news and ideas – to enter the village on a daily basis.

Internment camps

In Dublin, events were moving apace. After the rising, the rebels had been rounded up and incarcerated, including Dublin-based (but Crehelp-born) Joseph Byrne. Many of these prisoners were transferred to Britain, and the Frongoch internment camp in Wales became a centre for Irish rebels. Some other west Wicklow natives, such as Tom Cullen of Blessington and Patsy Kavanagh of Rathballylong were held in Frongoch,[6] a place where many rebels strengthened their resolve to continue the struggle for independence after their release. Those releases began during the summer months. Joseph Byrne’s release was announced in the local press on 17 June, in a report which attributed it to ‘the efforts of Mr. John T. Donovan, M.P. [whose] indefatigable exertions in the interests of the imprisoned relatives of his constituents and the people of County Wicklow are deservedly much appreciated’.[7] Byrne was released in July,[8] as was Patsy Kavanagh,[9] but Tom Cullen had to wait until December 1916 for his release.[10] Cullen returned from his incarceration to a changed Ireland, where the fortunes of the Irish Parliamentary Party were rapidly declining and where the rise of Sinn Féin marked it out as the new political force. John T. Donovan’s ‘indefatigable exertions’ were evidently not enough to stem the tide, and West Wicklow was no exception to this new trend of Sinn Féin advancement in late 1916 and early 1917. The resurgent party continued to grow in strength in and around the Dunlavin area throughout 1917.

A newly invigorated Sinn Féin

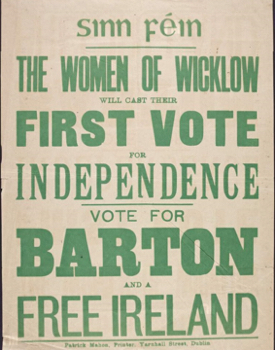

The original Sinn Féin party was founded in 1905 under the leadership of Arthur Griffith. Politically he viewed Home Rule as inadequate and aspired to a republic, but felt that there would be little or no support for revolution or war with Britain. Therefore, he propounded what he perceived as the ‘middle way’ of dual monarchy, based on the Austro-Hungarian model after the Ausgleich of 1867. Economically, Griffith believed that Ireland should be as self-sufficient as possible, and he advocated a policy of protectionism for indigenous Irish industries, akin to the Frederick List-influenced economic policies in Germany after the unification of the empire in 1871.[11] However, Griffith’s ideas garnered little support and his party languished in the political mire, until the 1916 Rising was erroneously (but perhaps serendipitously) labelled ‘The Sinn Féin Rebellion’ in press reports about Easter Week. Griffith was interned after the rebellion and spent time in Reading Gaol. He was released on Christmas Eve 1916, and quickly set to work to rebuild the party during 1917. The name of Sinn Féin was now an integral part of mainstream Irish politics and Griffith put forward the party’s platform of abstaining from taking seats in Westminster, establishing a parliament in Dublin and an Irish government to run the country and appealing to any post-World War One conference to recognise Ireland’s right to self-determination as propounded by President Woodrow Wilson.[12] Sinn Féin also continued to advocate economic self-sufficiency and the promotion of native Irish industry. Indeed, a Sinn Féin handbill for the general election of the following year focused on the demise of many extinct industrial ventures in west Wicklow, and specifically referred to some former local industries, including linen in Dunlavin.[13] The policies of Griffith and Sinn Féin eventually attracted some support in west Wicklow and the party made inroads in and around Dunlavin and its environs.

Fig 1: Sinn Féin election handbill for Robert Barton (west Wicklow candidate in 1918). Source: N.L.I., Department of Ephemera, EPH B231.

Meeting at Baltinglass

The Dunlavin Fife and Drum Band performed at a huge Sinn Féin meeting and aeridheacht in Baltinglass on Sunday 21 October 1917. It is very probable that there were many other Dunlavin residents among the attendance of two thousand people or so. The principal speaker was Laurence Ginnell, formerly of the Irish Parliamentary Party but now of Sinn Féin. Ginnell (1854-1923) was a native of Delvin, Co. Westmeath. He was elected as a Home Ruler in 1906 and sat as an independent Nationalist from 1909 onwards. He strongly criticised the British Government for the 1916 executions. On 9 May he accused the British Prime Minister, Asquith, of murder, and was escorted out of the House of Commons. Following de Valera’s electoral victory in East Clare, on 10 July 1917, Ginnell resigned his parliamentary seat and joined Sinn Féin.[14]

At Baltinglass, Ginnell said he was ‘proud to see such a fine assembly of the mountaineers of Wicklow; to find so many of the true old blood of the Kavanaghs, the Byrnes and the Kinsellas and the rest, whose forefathers lived amongst the hills and defended them against the invader’. He assured his listeners that the Sinn Féin ‘policy now being put before the country was the wisest, the noblest, the surest and the only policy for the regeneration of Ireland’. Advocating economic independence, Ginnell noted that ‘today, there is no direct trade between Ireland and any other country… they must sell to England at a price fixed by England’. ‘Ireland’, he said, ‘wants to build up her trade and commerce, wants to build up a proper system of education, wants to restore the people to the land, wants to drain the land’ but he maintained that the Home Rule Bill would not allow them these freedoms. In contrast, he assured them that Sinn Féin was ‘a great policy when correctly understood’. According to Ginnell, the Irish people ‘will not accept any [Home Rule] settlement now. They say that England has no right to rule in this country any more than Ireland has a right to rule in England. By sending members to Westminster, Ireland acknowledged that Britain had a right to rule in this country’. Ginnell made an impassioned plea, saying that he ‘wanted the young men to come in and join the Sinn Féin branches in their district. It was not enough to come there and cheer him. There was a great deal of work to be done and the young women should also join up, because they were very clever in many ways and could give great help’. Ginnell maintained that Sinn Fein ‘clubs would be a centre place where Volunteer views would come under consideration… they wanted the young men to feel they were part of the Irish nation… [if they] come into the Sinn Féin clubs they would be astonished what new strength would be given to them. They would be proud to find they were united under the living Irish nation here and with the Irish race abroad’. Ginnell ended on a rousing note, avowing that Sinn Féin was a ‘magnificent thing embracing the whole Irish cause, living up to the traditions of the old Irish nation and inspired with unconquerable courage’.[15]

Baltinglass public house raided

Ginnell’s linking of Sinn Féin with the Volunteers was significant. Some two months previously, a large contingent of RIC men, led by D. I. Egan and Head Constable Taylor of Dunlavin raided a public house in Baltinglass in the small hours of the morning. When Mr. J. Kitson admitted them to the premises they seized a cache of rifles and bayonets that he had in his possession. The police removed the weapons, which had been in storage for the local Volunteers. The incident demonstrates that the Volunteers were still a force in west Wicklow, and that there were still arms in circulation in the locality. Volunteer reorganisation went ahead rapidly, particularly from the first phase of Frongoch releases onwards. Nationally, the link between the two organisations was cemented at the Sinn Féin árd fheis in October 1917, when Arthur Griffith stood down as president in favour of Éamon De Valera, the senior surviving commandant of the Easter Rising.[16] On the day after the Sinn Féin árd fheis, the Volunteers also elected De Valera as their president. Thus, the two Republican movements, political and military, had a common front and were closely intertwined. From October 1917 onwards, the growth of Sinn Féin also involved concurrent growth in the resurgent volunteer movement. Sinn Féin held a ‘monster meeting in assertion of the claims of the small nation of Ireland’ in Dunlavin on Sunday 18 November 1917, which was addressed by ‘Mr. M. Lennon, Dr. T. Dillon and other prominent leaders of the Sinn Féin organisation’.[17] Given their close ties with the Volunteers in late 1917, it is very probable that this Sinn Féin meeting also increased support for the Volunteer movement in Dunlavin.

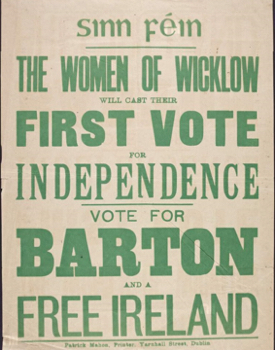

Fig 2: Sinn Fein election poster 1918, addressed to ‘The women of Wicklow’. Source: http://catalogue.nli.ie/Record/vtls000266109

Within a year or so, three major events had a huge impact on life in Dunlavin and the rest of Ireland. Firstly, the onset of the great flu pandemic greatly affected the village. As Ida Milne has observed: ‘The Spanish influenza pandemic silenced whole communities as it passed through, extracting a devastating death toll and even more astounding numbers of sufferers’.[18] According to Leo Dempsey of Dunlavin ‘In this town alone there was an average of three deaths a week and in many houses whole families were stricken down; very few people attended the wakes for fear of themselves becoming victims of the disease’.[19] The second outbreak of the pandemic was rife in November 1918, when the Great War ended. The armistice was another major event, but soldiers returning to Dunlavin would come back to a changed village. Thirdly, the new political reality was anticipated when a general election was called immediately after the end of the war. The election of 14 December, 1918 was the first one in which women could vote. The Representation of the People Act (1918) had given the vote to women of thirty years old and over (subject to a property qualification), and legislation was then introduced to allow women to stand for election themselves. [20] In west Wicklow, a Sinn Féin poster hoped that ‘the women of Wicklow would cast their first vote for independence, Robert Barton and a free Ireland’. [21] The recent threat of conscription and the wave of arrests in the wake of the ‘German Plot’ of May 1918 helped to galvanize support for Sinn Féin, and many Dunlavin voters, both female and male, must have celebrated when Barton was indeed returned for west Wicklow,[22] and a new political era dawned.

ENDNOTES

[1] http://centenaries.nationalarchives.ie/centenaries/plic/about.jsp (visited on 7 Jan 2019).

[2] N.A.I., Property Losses (Ireland) Committee, compensation files, PLIC/1/3314. Maguire was described as a ‘publican’s assistant’ and he used the spelling ‘Cryhelp’ to denote his home place.

[3] N.A.I., Property Losses (Ireland) Committee, compensation files, PLIC/1/5431.

[4] N.A.I., Property Losses (Ireland) Committee, compensation files, PLIC/1/4459.

[5] Cora Crampton, ‘The Tullow Line’, Journal of the West Wicklow Historical Society, i (1983-4), p. 8.

[6] Martin Timmons, Wicklow and the 1916 rising (Greystones, 2016), p. 42 and Paul P. Tyrrell ‘Patrick (Patsy) Kavanagh (1897-1957) of Rathballylong, Co Wicklow’ in Federation of Local History Societies’ Journal, 22 (2017), p. 103.

[7] Leinster Leader, 17 Jun 1916.

[8] Irish Military Archive, Military Service Pensions Collection, SP9212, (W24SP9212JOSEPHJOHNBYRNE online pdf, visited 10 Dec 2019).

[9] Tyrrell ‘Patrick (Patsy) Kavanagh’, p. 103.

[10] Timmons, Wicklow and the 1916 rising, p. 42.

[11] Arthur Griffith, The resurrection of Hungary: a parallel for Ireland (Dublin, 1904), passim. For an overview of and commentary on Griffith’s political and economic policies, see Owen McGee, Arthur Griffith (Sallins, 2015), pp 73-95.

[12] Calton Younger, Arthur Griffith (Dublin, 1981), pp 60-7. See also McGee, Arthur Griffith, pp 163-172.

[13] N.L.I., 1918 Election Handbill, Department of Ephemera, EPH B231.

[14] https://www.rarebooks.ie/shop/books/d.o.r.a.-at-westminster (visited on 17 Jan 2019). Other speakers at the meeting included Alderman Walter Cole, personal friend of Arthur Griffith and honorary secretary of Sinn Féin in 1917. https://ucdculturalheritagecollections.com/2018/10/04/mother-father-and-ideal-friend/ (visited on 17 Jan 2019).

[15] Nationalist and Leinster Times, 27 Oct 1917.

[16] Younger, Arthur Griffith, p. 67.

[17] Leinster Leader, 10 Nov 1917.

[18] Ida Milne, Stacking the coffins: influenza, war and revolution in Ireland 1918-19 (Manchester, 2018), p. 5.

[19] UCD Archive, Irish Folklore Collection, The Schools’ Collection, Dunlavin N.S. (B), vol 914, f. 40.

[20] https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/electionsvoting/womenvote/case-study-the-right-to-vote/the-right-to-vote/birmingham-and-the-equal-franchise/1918-representation-of-the-people-act/ (visited on 12 Nov 2019). The franchise was also extended to all males of twenty-one years of age and over.

[21] http://catalogue.nli.ie/Record/vtls000266109 (visited on 12 Nov 2019).

[22] For a brief overview of the political career of Robert Barton, see Chris Lawlor, The little book of Wicklow (Dublin, 2014), pp 104-9.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page