IN the early years of the 19th century with the industrial revolution in full swing, the age of the Railway was at hand. Ireland’s first Railway (Dublin to Kingstown) was completed by the end of 1834 and on December 13 of that same year the first train “Hibernia” puffed her way out of Westland Row station, destination Kingstown. William Dargan’s dream had come true. Carlow born Dargan has justly earned the title “Father of the Irish Railways” on account of his long association with the growth and development of the Irish rail system. Concerning the building of the first railway line Dargan’s contract stated that he would complete the railway by June 1, 1834 with the added carrot of £50 for each week he was early and a stick (fine) of £100 for each week he was late. With almost 2,000 workers labouring and good labour relations, progress was quite rapid. There were however slight hiccups along the way, one of which was the numerous complaints from lady-bathers at Williamstown —“that during the dinner break, railway labourers were inclined to strip off entirely and plunge into the cool refreshing sea”. However Dargan’s deadline of June 1 passed and yet all was forgotten when for the cost of one shilling first class, eight pence second class and six pence third class, later that year, one could make their first rail journey in Ireland. Over 5,000 passengers were carried that day.

Southeast Expansion

It became only a matter of time before the proposal to extend the railway line to the south east was advanced. By August 1844 the Dalkey Railway line was in regular operation and later that year Isambard Kingdom Brunel (of Captain Robert Halpin’s “Great Eastern” fame) mentioned to the directors of the Dublin and Kingstown Railway (D.&K.R.) that his own company (the Great Western Railway) planned to build a line into South Wales and start a new sea route from Fishguard to what is now Rosslare. There would be a need for a line from Wexford to Dublin and that the directors of the Dublin – Kingstown might consider its construction as a joint venture. A new company was formed — the Waterford, Wexford, Wicklow and Dublin Railway. Later, perhaps the sheer audacity of employing the names of all four Irish southeast seaboard counties in the company’s title occasioned blushes in the boardroom for in 1848 the W.W.W.&D.R.’s name was changed to the more modest one of the Dublin and Wicklow Railway Company. Progress was not easy. The effects of the Great Famine did much to inhibit the D.&W.R.’s construction plans. The line reached Bray on July 10, 1854.

The Dublin and Kingstown Railway directors were in no way eager to join a project for a long line but offered to extend as far as Wicklow. By this time (1849) a small private tramway-railway was being used to carry copper ore from the Mines at Avoca to the port of Arklow while Lewis’ Topographical Directory (1837) states that over 400 tons of copper and lead ore from the neighbouring mines were being shipped weekly from the port of Wicklow. A railway would prove most beneficial to the quicker transportation of the ore. The Dublin and Kingstown directors however thought that the Wicklow part of the proposed new line might prove remunerative but that the south-eastern portion might not prove so thus the construction of the Railway line to Wicklow commenced under the directorship of William Dargan with Brunel as chief engineer.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel had already gained a world-wide reputation as an engineer through his earlier work on the Thames tunnel and the Clifton Suspension Bridge over the Avon Gorge at Bristol. The great steamship “S.S. Great Eastern” was his crowning jewel although dogged by ill-fortune throughout its maritime life. Brunel’s vast knowledge of engineering would prove invaluable in the construction of the line from Bray to Wicklow or so it was thought. The lie of the land proved difficult for the construction of a railway. The simplest and most obvious route inland would not prove as scenic and so the coastal route was chosen. Tunneling proved no obstacle to one of Brunel’s experience and yet alarmingly only three tunnels were included in the original design with many timber viaducts carrying the line around some coastal headlands.

Coastal Mystery

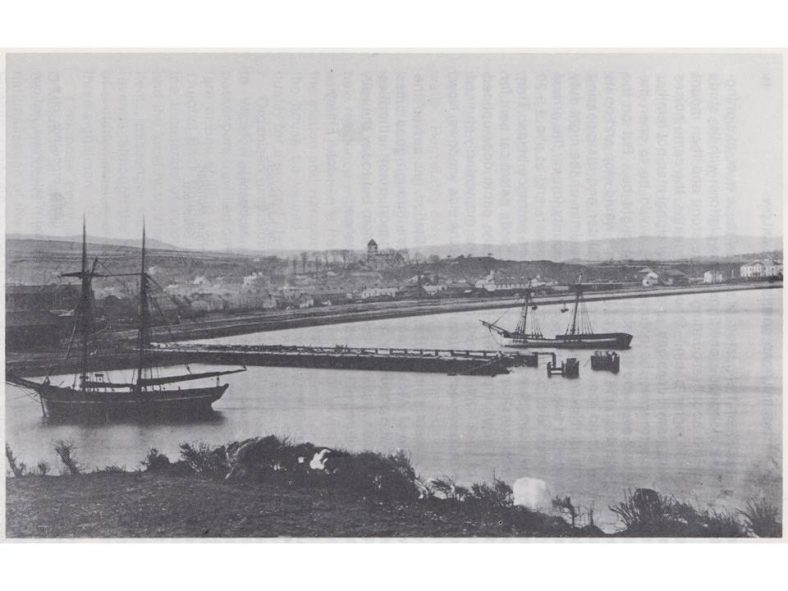

The Murrough in 1861 with wooden jetty near the site of present packet pier.

It is curious to speculate why with two such eminent and skilled men involved, the line was built so near the sea front. It very quickly showed itself unable to withstand the winter storms and so it became necessary to construct further tunnels and move the line not before it became known as “Brunel’s Folly”. Indeed the anxiety about the safety of the line around Bray Head was tragically justified when the Enniscorthy – Dublin train left the track while crossing one of the many wooden viaducts which bridged the sea inlets (1867). The engine smashed through the mainly feeble railguard and crashed bringing a number of coaches with it. Two passengers lost their lives with 23 others injured — some seriously. The laying of the line incorrectly was quoted as the cause of the disaster which occurred at place known locally as “The Brandy Hole” from its smuggling links. Eventually the Bray Head tunnel replaced the timber viaducts. Difficult as this operation had proved, the protection of the line between Greystones and Wicklow was even more problematic as at many points the line itself was almost on the sea shore. Coastal Protection was expensive and the line had to be moved inland on a number of occasions. To the present day the same line needs constant inspection. Eventually the new line to Wicklow was completed before the end of 1855 with the opening of the Murrough Station*. By August 20, 1861 the line was extended to Rathdrum. By July 18, 1863 to Avoca and on November 16,1863 the Enniscorthy line was opened. Wexford was reached on August 17, 1872. With the main line to the South East now completed the copper ore from Avoca Copper Mines was transported to Wicklow by rail and to aid its export a tramline was laid to the Packet Pier – North Quay along the Upper and Lower Strand Street**. Originally given by the Corporation of Wicklow free to the Railway Company, the land on which the Murrough Station stood was to prove controversial. With the proposed building of the new Mainline Station as early as 1877 and the use of the Murrough for goods and occasional excursions only, the Town Commissioners felt peeved at the misuse of their land and so with the early Charters of James I (1613) and James II (1688) in hand they made their way to London to fight their compensation claim. The Commissioners duly won and were awarded £500 in recompense.

With the opening of the new Mainline Station in 1886 the “old” station was used for goods traffic and its platform for occasional excursions and local passenger traffic. The extensive yard comprised several long sidings, a cattle bank for 28 wagons, a goods bank with a 3 ton crane, a fine goods store and a run round loop. Traffic dealt with included: cattle, sheep, beet, pulp, radiators, timber, tar, Guinness, sugar, cement, fertiliser, washing machines, pit props and a large amount of sundries. Due to rationalisation it was closed to all goods on September 6, 1976 and all traffic ceased on and from November 1, 1976.

With the extension of the railway line from Wicklow to Wexford, the Board decided to establish a new station on the main line some distance outside the town. In 1877 land was purchased for this purpose but some difficulties emerged about title. When these were eventually resolved, the station was built in 1884 and was inspected by the Board of Trade in February, 1885. Some changes were found necessary and on the company’s promise to make these good, permission was given to open the new station. There were objections from Francis Wakefield† and the Town Clerk who demanded the reinstatement of the “old” station but the Company replied that its action was within its rights and proceeded as planned. To soften the blow a subscription of £15 was made to Wicklow Regatta. Thus Wicklow Mainline was opened in 1886 and Wicklow Murrough was closed to passenger traffic.

Correspondence which appeared in the Wicklow Newsletter of February 14, 1885 re “The New Railway Station at Bollarney” showed the local interest in the railway. One such letter goes as follows:

Sir,

I am informed that the new Railway Station at Bollarney will soon be open for traffic and as the distance from the town is considerable, passengers will doubtless avail themselves of the shortest and most expeditious route thereto. I would therefore suggest, through your columns, that the attentions of the proper authorities be called to the roadway known as “Brick-Lane” (Brickfield Lane) adjoining Church Hill, via the Cricket field, with a view to having it put in good repair, as it is the shortest and most direct way for pedestrians to reach trains. It leads up to and terminates just at the new station. I may add that from this road some of the most pleasing and picturesque views of the town and bay are obtainable. Visitors approaching Wicklow or departing from it, by this avenue, cannot fail to be struck by the magnificent surrounding scenery of lake, sea and mountain.

I am,

Your obedient servant,

Pro Bono Publico.

The Wicklow Newsletter of November 21, 1885 again appeals for a clean-up of “Brickfield Lane”, complaining that its earlier appeal had been ignored.

With the opening of the New Mainline Station, the Grand Jury wanted a new road to be built to the Courthouse. Many of the older inhabitants, or even the not so old, may well remember a number of trees along the roadside near the Parochial House and the old Franciscan Friary especially one at the junction of Marlton Road and Abbey Street which partially remains today and another near the Allied Irish Bank. The original plan was that the proposed new road should pass through the grounds of the Old Abbey. The Parish Priest of the time, William Canon Dillon refused to allow the monastery grounds to be desecrated in such a way but later relented a little to allow the road at Abbey Street to be widened considerably on the condition that none of the noble trees, which had proudly stood for many years, be felled. Thus a number of trees originally in the Abbey grounds came to stand outside the walls. Regrettably only one partially remains today.

The Dublin, Wicklow and Wexford Railway was always trying to increase passenger traffic and Wicklow was one of the stations chosen for the issue of 2-day return tickets at single fare to Dublin. Wicklow was also one of the several stations where a builder of a new residence within one mile of the station could obtain for himself or a nominee a free season ticket for seven years between the station and Harcourt Street. A first class ticket required that the house be valued at £30 or upwards while the valuation to qualify for a second class ticket was £20 – £30.

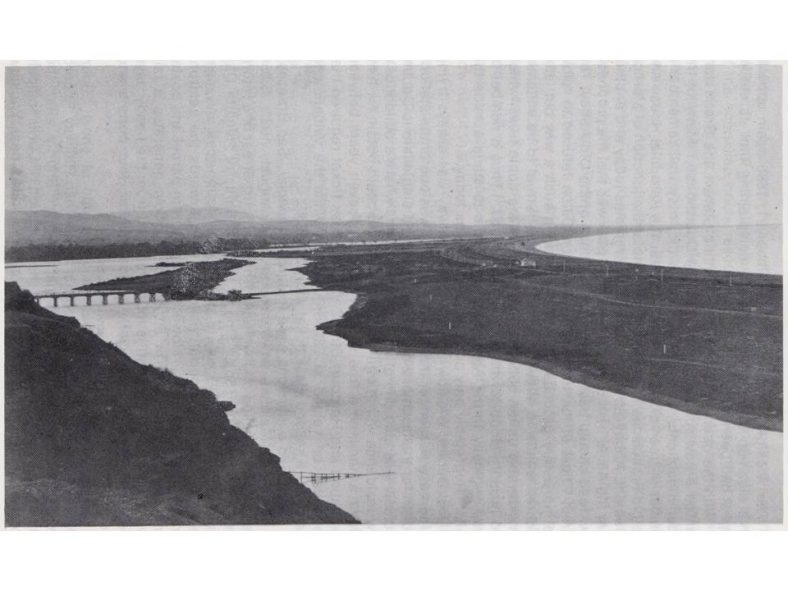

Bridge and embankment under construction to join Broadlough island to the mainland (circa 1860)

Organised excursions were features of special “Sea Breezes” to Wicklow (Mainline or Murrough). In August, 1932, 3,354 passengers travelled on five trains from Harcourt Street at a return fare of one shilling (5p). One of the highlights of Regatta Day (August Bank Holiday) was to stroll up the station road and meet the thousands of colourful visitors throng towards the seafront and the local hostelries. Nowadays, apart from parcel and postal items, passenger traffic in an out of Wicklow generates a fair revenue, although the staff is much reduced from the heady days of a station-master, chief clerk, goods-checker, four porters and three signalmen.

Ghosts of the Railway

I suppose every station has its own brand of ghost. John O’Meara in an article for the Journal of the Irish Railway Record Society recounts the following happening. “Shortly after the nationalisation of the railways with the formation of Coras lompair Eireann (January 1, 1945) two men were killed near Wicklow Station. It had been the custom of each of these men, at signing-off time to walk along the stone flags of the platform with the studs of the hobnailed boots resounding on the stone and then mount the steps to the signal cabin. Since the deaths, the same noises were heard on many occasions, and to any signal man not familiar with such occurrences, the natural thing would be to open the cabin door and see who the night guest might be. But on the opening of the door, the sound of footsteps would stop and on its closing they would resume, becoming fainter and disappearing into the night. In November, 1978 the signalman on the night duty was awaiting with two members of the security forces, the arrival of the down train with parcels and newspapers and at about 3.30 a.m. they saw a dim blue light at the station entrance below. They assumed that this indicated the visit of a garda patrol car sent for extra security. But after a few seconds the cabin door opened and a ball of blue light entered, passed the momentarily-stunned three men and disappeared through one of the side windows. Now, how about that!”

For over a century now the Mainline Station has served the town and people of Wicklow and its environs through good times and bad. Since the popularity of motor transport, many authorities sounded the death knell of the Irish rail system but today the railways face the future with increasing confidence.

John Finlay

* It had cost £369,431-16-1 to construct the line to Wicklow.

**Oak pit props for Welsh Coalmines from the Fitzwilliam Estate at Shillelagh were exported via Wicklow also. The rails were removed in 1927.

†Wakefield had invested in the Marine Hotel. This may help to explain his objection.

References

Journals of the “Irish Railway Record Society”.

Ireland’s First Railway by K. A. Murray.

Railways in Ireland 1834-1984 by Oliver Doyle and Stephen Kirsch.

Outline of Irish Railway History by H. C. Casserley.

Railway History in Pictures, Volumes I and II by Alan McCutcheon.

Irish Standard Gauge Railways by Tom Middlemass.

Irish Railways since 1916 by Michael H. C. Baker.

One hundred and fifty years of Irish Railways by Fergus Mulligan. The Dublin and South Eastern Railway by W. Ernest Shepherd.

Acknowledgements

The Society wishes to acknowledge the help given in the production of the Journal by Wicklow U.D.C., Wicklow County Council and Wicklow Press, and our patrons for their support.

No Comments

Add a comment about this page