From Cronalea to Emu Bay – Eliza Davis Revisited

“Mystery surrounds the whereabouts of both mother and child; the location of the child’s final resting place will probably never be known. ‘The fate of Eliza Davis, on the other hand, may yet be some day ,known……” (Read Part 1 here on this site)(1)

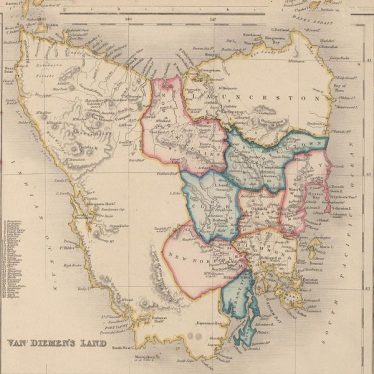

Historic Map of Van Diemen’s Land c. 1854

Transport to Tasmania

Scene on board the Tasmania convict ship (from a Dublin Newspaper, September lst, 1845) -,

As it was expected that the above vessel would sail on Saturday from Kingstown Harbour, anumber of persons proceeded to the, pier to witness the impressive and melancholy sight. T h e day was beautiful ….. and everything indicated peacefulness and happiness; but when the eye turned to the gloomy form of a convict ship as it lay upon those calm blue waters, a floating dungeon, the prison-home of the felon, exile, a sadness came o’er the mind from the reflection that however bright and lovely, and joyous all things round it seemed to be, within its dark and tomblike bosom were enclosed many suffering spirits, whose crimes had expatriated them from their native land ……. side by side knelt the miserable creature who poisoned her husband in Kilkenny and she who had drowned her infant in Wicklow when driven from the door of‘ her seducer…..(2)

The woman referred to in this newspaper article aboard the Tasmania (2), who was being transported for “strangling her infant in Wicklow”, had to be Eliza Davis. Here at last was a tangible reference to Eliza. She had been aboard the ship and had in all probability survived and landed in Van Diemen’s Land. What became of her on disembarking in Hobart? The following is an account of the details of Eliza’s life as it has unfolded through official archival material and family documents which have come to light through a series of amazing coincidences over the last eighteen months.

The Tasmania reached Hobart Town on December 9th, 1845 with 138 women and 37 children. En route one woman, Ellen Sullivan and a six month old baby, Patrick Ferguson, died. The journey according to the ship’s surgeon, Mr. Jason Lardner, was without any great mishap though a number of the women suffered great distress through seasickness while the dampness below decks also caused much discomfort. This latter problem was alleviated through additional stoves being brought down to the prison section. Ironically, the women were given extra rations of potatoes in September 1845, just as the blight was making its first appearance in Ireland. While two people died on board, a baby was also born during the voyage though to which convict is unclear.(3)

Transportation to the penal colony of New South Wales ceased in 1840 and Van Diemen’s Land became the main penal colony receiving over 36,000 convicts between 1840 and 1853 when transportation ceased.(4) The Irish made up almost one third of that figure. The transportation of females had caused problems for the authorities almost from the beginning; convicts of both sexes travelling together had many an inevitable outcome and led to the stereotyping of female convicts as prostitutes; single sex transportation as a result commenced in 1806. Once in the colony the convicts were assigned to settlers under certain conditions. The convicts’ clothes and food were provided by the settlers in return for cheap labour. Those who behaved could look forward to earning a ticket-of-leave which allowed them relative freedom and the right to work for wages. The granting of a complete pardon normally followed sometime later.

Photograph of Port Aurthur 1850’s

A Ticket-of Leave

Women convicts posed some difficulty for the authorities on landing, where they were kept in the Female House of Correction or “factory” at Parramatta or Hobart until they could be assigned. This often proved a protracted affair as due to stereo-typing few respectable settlers wished to have them, fearing the morals of their children would be subjected to the influence of these fallen women. In Van Diemen’s Land the situation became acute with the factory in Hobart overcrowded and dilapidated. Though sanction had been given for a new female penitentiary to be erected in Hobart inactivity seemed to be the order of the day on this matter. Instead the HMS Anson a former naval vessel was fitted out as a female probationary establishment in Chatham dockyard in 1843. Three thousand women were lodged on board the “Anson” at its berth off the Queen’s Domain on the River Derwent over a period of time.(5) Eliza Davis was one such woman.

According to her convict record sheet Eliza spent six months aboard the Anson where she was listed as a Class 3 prisoner.(6) She was released on June 16th, 1846. Also recorded in the sheet are details relating to her applications for a ticket-of-leave and a pardon as well as her marriage to a Joseph Roebuck. Joseph Roebuck arrived in Van Diemen’s Land in October 1841 on the David Clarke. A native of Pennington, Yorkshire, he was tried at York on July 6th, 1840. He was sentenced to ten years for stealing wearing apparel. As he had already been imprisoned on two previous occasions, once for poaching and once for having skeleton keys in his possession, it would have come as no surprise for him to be sentenced to transportation. He had received three months in gaol previously on each charge. This convict record states that he had an idle, bad character but that on board ship his report was good. He was a widower and was aged 36 in 1841.

Joseph had a period of probation of eighteen months at Brown’s river, now Kingston. In April 1843 he was charged with an offence of “misconduct in improperly receiving a half loaf from the bakehouse”. He received three months in return. By September 1843 he was at Campbell Town, being granted a ticket-of-leave in 1847. He was recommended for a conditional pardon in April 1848 which was approved in July 1849. According to his convict record he was five foot six and three quarter inches in height, with both brown hair, eyes and whiskers. A note refers to his being “pockpitted, with two rings on fingers left hand, hair mole on left arm.”

It is impossible to say how Eliza and Joseph would have met. As Joseph was also a convict it was necessary to apply for permission to marry.(8) Also recorded in the permission to marry index are two other applications for an Elizabeth Davis, per Tasmania, to marry. Approval was granted to marry a David Martin, per Lady Nugent, in February 1848 though this marriage did not take place. (9) However, a marriage between an Elizabeth Davis and a Henry Hedges did take place on May 6th, 1850. It can only be surmised that this Eliza Davis had in fact assumed this name.

On July 11th, 18th and 25th the banns were called for “Elizabeth Davis of Launceston, a convict and Joseph Roebuck of Campbell Town, holding a ticket-of-leave. The marriage took place on July 26th, 1847 in Campbell Town at St. Luke’s Church “according to the rites and ceremonies of the United Church of England and Ireland”. Joseph, aged 43, signed his own name, while Eliza signed with an “x”. Prior to the marriage taking place Eliza had given birth to twin daughters on May 20th, 1847 in St. John’s Hospital, Launceston. They were christened in Campbell Town in St, Luke’s Church on June 27th under the name of Davis and not Roebuck. They were Amelia Eleanor and Elizabeth. By June 1850 a son, Joseph Henry, was born to the couple in Hobart.(11)

A Tough Life

We next come across Eliza in the records in 1856 when Joseph was charged in the police office in Hobart Town of being of “unsound mind, unfit to be at large and unable of maintaining himself’. On September 24th evidence was taken by Mr Duncan McPherson and the Chief Superintendent of Police, Mr. J. Burgess, as to the condition of Joseph. A question as to his wife’s ability to assist towards his maintenance while in the asylum was posed. It would appear that this option had already been investigated by the examining magistrate who decided that this would not be possible as she, herself, had three children to provide for. Upon the sworn evidence of Dr. Edward Bedford, Joseph was to be “confined in His Majesty’s General Hospital at Hobart Town while awaiting the decision of his Excellency, The Governor”. Dr. Bedford had stated that he had seen Joseph on a number of occasions, once two years previously and again some months prior to the hearing. He found him to be “subject to epileptic fits and temporary insanity”. This piece of evidence, from Dr. Bedford is ironic as of course Eliza too suffered from epilepsy. It was this disability which many believed led Eliza to drown her baby. Its revelation after her trial was considered mitigating circumstance and led to the commutation from death to transportation for life.

It is through Eliza’s sworn evidence that we receive an insight into her life with Joseph over a period of time. According to her, Joseph had been unable to work for almost four years and it was through her labour that the family survived. “Sometimes I earn thirty shillings a week and sometimes less by taking in washing and mangling. I have no other means of procuring support for myself and family. And I am not able to pay for my husband’s treatment in hospital”. A further statement shed some light on her life with Joseph as his condition deteriorated. “My husband threatened me last week. He said he would kill me. He was in a worse state of mind then than he is at present. He was more violent. He threatened me on last Friday and Saturday – I am afraid that he will do me some bodily injury unless he is placed under restraint”.(12)

Joseph was committed to the New Norfolk Asylum where he remained until his death in September 1873. The cause of death was recorded as being “disease of the brain and natural decay”, verified by the Superintendent Medical Officer, G. F. Huston. Joseph was aged seventy three and was termed a pauper.

A New Start

Eliza & Amos Eastwood

Life for Eliza at this time must have been extremely hard, as she, most likely, continued to take in washing to keep herself and the three children, now aged nine and six. She possibly remained in Hobart Town which is the last known address until Eliza appears again in the Tasmanian Pioneer Index when another daughter, Alice, was born to her in Northern Van Diemen’s Land in May 1860. Eliza had reverted to her maiden name of Davis and the father was recorded as Amos Eastwood. This union was to produce six children in all; Sarah sometime in 1859, Harriet in September 1862, Hannah in May 1864, Amos in December 1865 and James in July 1869.

It must be remembered that during this ten year period Eliza was still married to Joseph Roebuck, but it can be assumed that Eliza and Amos probably lived quite openly as man and wife as the children were registered under the name of Eastwood and not Davis.

What of this man Amos Eastwood? He too was a convict who had come to Van Diemen’s Land via Colaba, near Bombay, India where he was court martialled for striking his superior officer. Like Joseph Roebuck, Amos too was a Yorkshire man from Doncaster. He was in the 78th Regiment stationed in India and struck Sergeant Scott in December 1850 for which he was transported aboard the “Royal Saxon”. He was of the Church of England denomination, could read and write a little and was aged twenty six when he arrived in 1851. His trade was given as that of wheelwright. His probationary period was for three and a half years, stationed firstly in the Prison Barracks (presumably Hobart) and then in 1852 Impression Bay, near the notorious convict depot at Port Arthur. By October of that year it stated he was “a pass holder”.

From 1853 to 1855 Amos’ convict record sheet contains details of a number of offences committed by him during that period. There are five instances listed where Amos was sentenced to various periods ofconfinement for drunk and disorderly conduct. Each offence occurred in Hobart; the first in November 1853 when he was confined to ten days solitary confinement in the Prison Barracks and then returned to service. On the second occasion in April 1854 he received fourteen days solitary. By June of that year, as well as being drunk and disorderly he was also out after hours and was sentenced to two months hard labour, after which he was returned to service. September saw him again in the Prison Barracks, this time for six months hard labour for being drunk and misconduct in resisting a constable. A note to the effect that he was not to return to service in Hobart was recorded. This pattern continued with another offence recorded in February 1855 when the charge was “misconduct in returning late under the influence of liquor and assaulting a constable”. He received six months hard labour on February 17th. By February 21st he had absconded. Nothing more is known of this episode.

The last entry relates to his certificate of freedom in 1858.(14) It is presumably around this period that he came in contact with Eliza Davis Roebuck and a relationship was formed, which as already stated, produced six children. Eliza and Amos obviously moved from Hobart in the south to the northern region of Morven, Longford and Launceston and eventually to the Emu Bay port settlement district, later named Burnie.

Life At Emu Bay

Emu Bay was established by the Van Diemen’s Land Company as a primitive port and service centre for stock and farm supplies. This was a company set up by English investors in 1825 to exploit the great wealth to be found in Australia. An area of 350,000 acres was settled by the Company, 120,000 acres of which were in the Burnie district. It was so named by a surveyor after a river near which he had found emu prints and was one of the few areas of the north-western coastline with deep water potential. But the landscape was heavily forested with almost impenetrable rain forest stretching from the shoreline thirty or forty miles inland. Only a handful of people lived there with it functioning merely as an outpost. The discovery that once the land was cleared the area had a deep rich loam of remarkable fertility was not made until the 1840s. Settlers moved into the area but few wished to stay in Emu Bay which was accessible only by sea. The mining of tin at Mt. Bischoff in 1871 changed Emu Bay dramatically.

According to the “Pioneers of Burnie” Amos Eastwood married a Launceston girl and moved to Burnie in 1868 occupying a house on Marine Terrace at the junction of Brickwell Street. It was a felicitous move for Amos as a year or so later as wheelwright for Burnie blacksmith John Mylas, he faced a major challenge in building and repairing wheels for the dozens of bullock wagons carting Mt. Bischoff ore and general goods. Amos junior, born in 1865, “as a boy spent a half day at school and the remainder working for the Van Diemen’s Land Company swimming numerous horses, working the Mt. Bischoff tramway, in the sea”.

On conversion from a tramway to a railway Amos joined the Emu Bay and Mt. Bischoff Railway Company and became a train driver. In 1905 he bought a 34 acre dairy farm. He died in 1931 aged 65 years. His son, Cliff, bought a 270 acre property which he worked up to his retirement in 1969. He donated eight acres to the Burnie Council in 1964 which is now a tennis court centre and park and has been named “Eastwood Reserve”. (I5)

The penultimate document relating to Eliza, to date, is her marriage to Amos Eastwood, dated October 12th, 1898, almost forty years after the birth of their first child. Elizabeth Roebuck was recorded as being 68 years old and a widow. The wedding ceremony was conducted “according to the usages of the Primitive Methodist Church” in Emu Bay between Eliza and Amos Eastwood on that date. From this certificate we learn that Amos was bachelor and a wheelwright by profession. He was aged 72 and was born in Doncaster, Yorkshire. His parents were Amos and Mary Eastwood and his father had also been a wheelwright. Eliza’s husband, it states, had died at New Norfolk Asylum. A comment of “cannot remember the year” was recorded. Her birth-place was Wicklow, Ireland, and her parents were not known. Elizabeth signed the certificate with “her mark”. On her transportation record in 1845 she had been able to read only. Fifty three years later it would appear that she could still only read.

Elizabeth stated that she had only three children living (this statement is true in that she had only three children alive bearing the name Roebuck, but also by this time she had given birth to six children, all of whom were registered under the surname of Eastwood). The marriage was witnessed by Amelia Helen Coldhill from Latrobe, and Harriet Whitton, from Burnie. Both were Eliza’s daughters; Amelia from her first marriage, who in turn married David Coldhill and Harriet, born in 1862, who married Thomas Whitton and was in fact witnessing her parents’ marriage.(16)

The Story Ends

One week later, on October 19th, Eliza Davis Roebuck Eastwood died. She was according to the death certificate, aged 69 (born in England) and the cause of death was Cerebral Apoplexy. (17) the closeness of these dates – her marriage on October 12th and her death by October 19th begs the following questions; Were Eliza and Amos aware of her impending death or was it a mere coincidence? Did Amos wish to make “an honest woman” of Eliza before her death? Why did they marry? Why did they not marry sooner, after Joseph Roebuck’s death in fact, in 1873? These questions have been put to various people in Tasmania and New Zealand, but no definitive conclusion has been arrived at. Perhaps, like other aspects of Eliza’s life, we will never know the real answer! Maybe that is what is so intriguing about this woman, that the, reader can decide for him or herself where the real truth lies.

On reading Eliza Davis’ file in the National Archives over five years ago I was intrigued and fascinated by her story; not just by what was contained in the file, but also by what was missing. What had become of Eliza? Had she survived the journey to Van Diemen’s Land? Had she survived the convict system? Had she ever married and had children? Did a woman whose very origin lay in tragedy ever achieve a sense of happiness, fulfillment or success? Once again these questions cannot be answered conclusively but it can only be assumed that she did achieve some happiness with Joseph initially and then ultimately with Amos and her nine children.

And so the story of Eliza Davis ends with her death in 1898. But in many ways her story is only just beginning; certainly for her descendants in Australia and New Zealand, some of whom were not aware of the true nature of the crime for which she was transported in 1845. Believing that she had been convicted of petty-thieving, the crime of infanticide was something which one descendant felt he had “to come to terms with”. He also felt however, that it was a different age and it was not his place to pass judgement on a woman faced with being an unmarried mother in mid-19th century Ireland.

Footnotes:

I am deeply indebted to the following people without whose assistance this article would not have been possible: Ray Thorburn, the late Denise McNeice, Thelma McKay, George Hughes and Gail Mulhearn.

(1) “The Case of Eliza Davis“ by Joan Kavanagh in County Wicklow Historical Society Journal Vol.1, No. 7 1994 (see http://www.countywicklowheritage.org/page/the_case_of_eliza_davis).

(2) Extract from the Hobart Town Courier and Government Gazette, Saturday Morning December 13, 1845.

(3) Journal of His Majesty’s Convict Ship “Tasmania”, Mr. Jason Lardner, Surgeon. P.R.O. London ADM 101/7/1/2.

(4) Williams, John “Ordered to the Island” (Sydney, 1994) p.101.

(5) Brand, Ian, “The Convict Probation System” – VDL 1839-54. P.271 Smith, Coultman, “Shadow Over Tasmania”. P. 108.

(6) Archives Office of Tasmania (AOT) CON 41/8.

(7) AOT CON 33/13.

(8) AOT CON 52/2 p. 178.

(9) AOT CON 52/2 p. 415.

(1 0) AOT CON NS 119/03.

(1 1) I am greatly indebted to Denise McNeice & Thelma McKay of the Genealogical Society of Tasmania for their efforts in locating this data in the AOT.

(1 2) AOT HSD 285/21.

(13) The Hughes-Eastwood family tree courtesy of George Hughes.

‘(14) AOT CON 37/7 No. 2170.

(15) Pike, Richard, “Pioneers of Burnie”.A sesquicentenary publication 1827-1977 pp. 30-3 I.

(16) Certificate of marriage No. 109 District of Emu Bay, Register No.13.

(17) Deaths in the District of Emu Bay 1898 No. 471.

Comments about this page

I too, have Eliza as my 4th Great Grandmother, my family descend through Amelia Helen Roebuck. What a tough lady was Eliza! From Ireland to Tasmania, and then Amelia travelled north into NSW and planted the seeds to my family tree. I would never have found any of them if not for taking an ancestry DNA test. Very proud to be another strong woman sprouting from a strong and resilient tree branch, attached to some very strong Irish roots. Tanya Sawyer.

Eliza Davis is my 4th Great Grand mother from her first child with Amos Eastwood. I am so proud of Eliza. She had a very tough life and cant imagine what she went through in her life. I tell everyone about her story and thankful for the people who fought for her to come to Australia as I wont be here if they didn’t.

Add a comment about this page