In Search Of The Judge's Monument

In an obscure corner of Christ Church Cathedral, away from public view, rests the monument – or what survives of it – of Chief Justice William Whitshed. Now forgotten except by legal and literary historians, Whitshed was a notable figure in early eighteenth-century Ireland, a man who excited fear and hatred as well as respect in his contemporaries and who had a particular connection, as MP and landlord, with the North Wicklow area. When Whitshed died in 1727, his estate included lands at Killincarrick, near present-day Greystones, as well as in the city and county of Dublin. Since he was unmarried, his property was inherited by a brother and in turn by his descendants, and over the two centuries which followed, the Hawkins-Whitshed family left its mark on the locality: six members of the family represented Wicklow constituencies in the Irish House of Commons between 1692 and 1771; their eighteenth-century house is still just about recognizable in its present form as the headquarters of Greystones Golf Club, while the Edwardian housing development established on Hawkins-Whitshed lands has provided Greystones with a unique architectural heritage. But little is known of the judge himself, of his Swiftian connections, or of his eventual resting place.

The Judge And The Swiftian Connection

William Whitshed was born in 1679, the eldest of thirteen children of Thomas Whitshed, a barrister, and his wife Mary. Having followed his father into the law, he was elected MP for Wicklow in 1703, was appointed Solicitor General in 1709 and Chief Justice of the King’s Bench in 1714. He is best remembered as the object of Swift’s fury and contempt: in 1720 he presided over the trial of the printer of the Dean’s anonymous pamphlet ‘For the universal use of Irish manufactures’, and in 1724 over that of the printer of his fourth Drapier’s Letter, but despite strenuous efforts, was unable to persuade the jury to convict. In a series of verses such as ‘Verses on an upright judge’ and ‘Whitshed’s motto on his coach’, the Dean castigated the judge as an unjust and vindictive lawgiver, as an avaricious tool of the Lord Lieutenant, and as a rapacious landlord.

My dear estate, how well I love it,

My tenants, if you doubt, will prove it,

They swear I am so kind and good,

I hug them till I squeeze their blood.

More questionably, Swift resurrected an ancient scandal with which to taunt his enemy: in 1674 Whitshed’s maternal grandfather, Mark Quin, a former Lord Mayor of Dublin and one of the city’s wealthiest men, cut his throat ‘with a new bought razor between the hours of nine and ten in the morning, in or near the Chapel of St Mary, in Christ Church’, reportedly ‘in a fit of jealousy at the conduct of his wife.’

In church your grandsire cut his throat,

To do the job too long he tarried,

He should have had my hearty vote,

To cut his throat before he married.

The legal historian Duhigg, following Swift’s line, took a highly critical view of Whitshed: while admitting his ‘considerable legal talent, and unexceptionable personal character’, he condemned his ‘perjured zeal, and presumptuous tyrannical practice’, and charged him with having ‘exercised, without scruple or even pecuniary bribes, petty hatred and personal malevolence in many private causes.’ Whatever his faults, a contemporary anecdote suggests that the judge was a man who knew how to keep his head in a crisis. When smoke from a neighbouring chimney fire filled the courtroom in which he was sitting, panic ensued. A number of people were killed in the rush to escape, and one of his colleagues ‘got half in and half out of a window, but could not pass through, lost his wig and at last was forced back.’ Whitshed alone remained calm, and ‘kept his place and temper till at last the truth was known.’

Final Resting Place

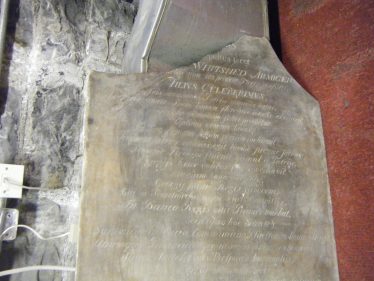

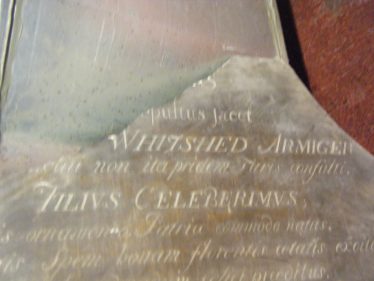

In 1727 Whitshed, then in his late forties, was described as finding ‘the business of his present station very fatiguing as he advances in life.’ He died shortly afterwards, and was buried in the medieval church of St Michael’s on the Hill, close to Christ Church Cathedral. A ‘shield-shaped’ tablet was set up in his memory in the church porch, for whose upkeep his descendants allotted an annual sum of £2. The inscription, in Latin, described him as ‘born to be an ornament to his own family as for his country’s good’, praised him ‘as a judge, unwearied, perspicuous, uncorrupted’, and extolled his ‘very happy intellect … highest learning’ and ‘supreme legal skill.’

And there, sheltered beneath this kindly epitaph and safe at last from Swift’s venom, Judge Whitshed might have rested for eternity. But in 1890, when restoration work was being carried out on Christ Church Cathedral, St Michael’s was demolished to make way for the new Synod Hall, and the Whitshed monument was one of those removed to the Cathedral. And there it still languishes, first in the crypt, where sometime in the 1990s some builders walked over it, breaking it in half. It was then removed to the archives, but even this was not sufficient to protect it from damage. Late last year it suffered a further breakage and the disappearance of one of the fragments, and it was in that condition that I photographed it in February 2013. Unlike Swift’s ‘monument more lasting than brass’, the judge’s memorial has proved sadly ephemeral, and the run of misfortune begun when he crossed swords with the greatest satirist of the age has, it seems, continued well beyond the grave.

Bartholomew Duhigg, History of the King’s Inns (1806)

Jonathan Swift, Works, vol X (1814)

F Elrington Ball, The judges in Ireland, 1221-1921 (1926)

Edith Johnston-Liik, History of the Irish parliament (2002)

Paul J DeGategno, R Jay Stubblefield, Critical companion to Jonathan Swift: a literary reference to his life and works (2006)

The Irish Builder , 15 November 1891

Rosemary Raughter, ‘The judge, the admiral and the lady alpinist: the Hawkins-Whitshed family of Killincarrick and Greystones’, Greystones: its buildings and history (2012)

No Comments

Add a comment about this page